… it is helpful to think of architectures as ‘archi-textures’, to treat each monument or building, viewed in its surroundings and context, in the populated area and associated networks in which it is set down, as part of a particular production of space.

HENRY LEFEBVRE, The Production of Space

This article explores how the concepts of space and place shaped my research and approach to architectural design, leading me to seek their universal meanings beyond their specific architectural connotations. That shift of focus, from the particular to the universal, eventually coincided with a turn of my interest from space to place, and a reevaluation of their traditional meanings, as I came to realize that reality is composed of concrete places, things, and bodies, and that space is an abstract concept often mistaken for the actual environment in which they exist and move. At RSaP—Rethinking Space and Place, I have argued that our excessive use of spatial metaphors leads to a loss of cognitive distinction between concrete, place-based realities and abstract, space-based domains. We would better understand the physical environment, or any part of it, as a place-world rather than ‘space’, an issue that American psychologist James J. Gibson also understood from his unique perspective, thanks to his groundbreaking studies on perception and the environment (see James J. Gibson on the Concept of Space).

The following narration is based on events that took place during my time as a student at the School of Architecture – Politecnico di Milano, in the mid 1990s. This reconstruction, like any other, is barely a faint image of the actual events and circumstances, with many crucial connections between them lost or forgotten. However, the remaining content, presented in this article, has significantly contributed to the evolution of my understanding of spatial concepts and my subsequent shift in perspective. Ultimately, I believe this personal narrative may provide valuable insights for architecture students, scholars of spatial concepts, and my colleagues who, although rooted in classical concepts of space and place (with which they grew up and established their professional careers), may find some arguments for a shift in perspective convincing and difficult to refute.

1. Preliminaries to Understanding Architecture and Space

As I mentioned in the article On Architecture, my interest in architecture, even if unconscious, originated from memorable childhood experiences, which were shaped by distinct architectural backgrounds, such as a cathedral, a sports arena, a cinema, or a particular house, etc., which I could now describe as a foreground for those experiences rather than a background. Those precious moments, which were inextricably linked to specific architectures and their atmospheres, aroused strong sensations in my body, while also affecting my mind and my memories. I will now focus on the passages that helped me recognize and understand the architectural significance of those experiences, articulate them, and elevate them to a conscious, rational level, ultimately developing a mode of architectural expression that views architecture as part of a larger environment, interconnected with it. A few years later, after reading Henry Lefebvre’s The Production of Space, I termed those modes of architectural expressions ‘archi-textures’, borrowing the term from the French author. These archi-textures (‘archi-trame’ in Italian) inherently contained the seeds to challenge traditional concepts of space and place and, consequently, reexamine the meaning of architectural phenomena from a more universal perspective.

This is a journey that began in the early ‘90s when I enrolled at the School of Architecture – Politecnico di Milano. The early years were not easy, for me: I excelled in historical and theoretical courses, but struggled with what truly mattered to me – designing beautiful buildings, the reason I wanted to become an architect –, as my initial projects were poor and looked awful to me. Although my grades on my first architectural projects were decent, they didn’t encourage me: how could I reverse what I saw as a disappointing aesthetic trend in my projects?

In the early ‘90s, my Alma Mater was torn between internal stylistic battles, particularly between rationalism and postmodernism. Personalities like Giorgio Grassi, Vittorio Gregotti, and Aldo Rossi — all of them graduated from the Politecnico — dominated the Italian architectural scene. Italian students in the ’90s, especially those in Milano, could hardly neglect their influence. Yet, my school was open-minded enough to accept the influence of contemporary international trends, such as deconstructivism and the evergreen organicism, both of which had a representative force in Italy: the charismatic work of historian and critic Bruno Zevi. These alternative trends were diffused among students, but teachers in Milano largely ignored them, instead adhering to the views of the dominant rationalist and postmodernist parties.

Indeed, all of those architectural inputs were vastly different and contrasting. In retrospect, I’ve learned that an overwhelming amount of information from diverse sources can lead to chaos, or effectively no information at all, unless you have tools to separate the wheat from the chaff. Back then, I lacked the necessary tools, and — alas — my idiosyncrasy to blind conformism prevented me from confidently following a specific stylistic trend. As a result, my early architectural projects, driven by formal or stylistic considerations, lacked order and coherence, reflecting my inability to see beyond the surface level. At that time, I thought architecture was about creating beautiful hand-drawn perspectives, orthogonal projections, and bird’s-eye views (computer-aided design was just emerging), unaware that these were merely the outcome of many underlying processes. In my mind, architecture mainly involved designing and assembling attractive facades and functional plans, without realizing the connection between the two. Fundamentally, I saw architecture as an ‘external’ phenomenon, something controlled from the outside and from above by the architect’s mind and hand, much like a creator, a demiurge, or deus ex machina – an image that remains popular in the building sector, where the ‘archi-star’ represents the highest legacy of this outdated perspective on the architect’s profession.

To overcome the initial architectural difficulties, I intensified my studies of the masters of modern architecture — including Frank Lloyd Wright, Adolf Loos, Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto, Louis Khan, etc. — and explored various theoretical approaches, such as organicism, constructivism, suprematism, modernism, Bauhaus, De Stijl, etc. There were highly interesting aspects in all of them, even if they had very different approaches. Of course, I also studied famous buildings on paper and in person whenever possible. In the early ‘90s, I began spending my summer holidays traveling extensively throughout Europe by train, carrying an heavy backpack, exploring remarkable places and their historical, modern, and contemporary architectures, from Helsinki to Lisbon and from Glasgow to Vienna.

Gallery 1 (clockwise, Image 1, 2, 3): Laon Cathedral, Laon, FR, (1170). Image 2: photography by Andrew J. Tallon.

Moreover, like other students passionate about architecture, I too would browse through architectural magazines from around the world, hoping to find inspiration or guidance in designing beautiful buildings from the stunning images of buildings and projects. That did not happen. The long-standing, unsolved problem remained: how to synthesize numerous sources of beauty and interesting information into a coherent understanding and image of the architectural phenomenon.[1]

During those initial years of seemingly unproductive exploration, I realized that for a hybrid discipline like architecture, which combines art and science, goodwill and hard work alone are insufficient. Achieving beauty that combines with utility, or form with function, requires more than just determination or diligence.[2] The ‘artistic’ aspect of architecture, indeed the artistic aspect of everything, is nearly inexplicable, going beyond established standards, norms, and recipes, which are often documented in books due to their ease of communication, but these are merely quantitative factors. On the other hand, the artistic side of things is initially driven by qualitative factors, which are difficult or impossible to formalize or crystallize into transmissible knowledge, since quality is elusive, fleeting, and cannot be described in any encyclopedia.[3] Most importantly, I soon realized that, within the limits of a young student’s knowledge, science and norms, including the essential engineering and technological aspects that enable buildings to function and be solid, were insufficient to produce beautiful or interesting projects.[4] And if you ask me what is meant for ‘beautiful’ or ‘interesting’, today, like yesterday, I am quite confident in saying that a building that fails to evoke some kind of positive emotion (or well-being) in its inhabitants cannot be considered beautiful or interesting.

So, I felt lost, as if stuck in an architectural limbo or a labyrinth with no exit, but eventually, the various insights I gathered during my wanderings fell into place, and things changed for the better.[5]

My initial interest in the aesthetic aspects of architecture, particularly the lack of aesthetic qualities I saw in my early projects, motivated me to explore the field of aesthetics, for guidance on how to improve their quality. Aesthetics has a dual meaning stemming from two distinct philosophical roots: on one hand, it is a philosophical inquiry into sensuous perception, as derived from Kant’s philosophy; on the other hand, it refers to ‘the criticism of the beautiful or to the theory of taste’, a more common understanding today, rooted in A. T. Baumgarten’s philosophical theory ‘Aesthetica’ — with the term aesthetic originating from the Greek word aisthētikós, from the verb aisthanesthai, meaning ‘to perceive’.[6] This latter sense, derived from Baumgarten, is why we instinctively link the term ‘aesthetic’ with ‘beauty’. It is because of the first sense that we can link beauty to sensuous perception. The field of aesthetics, with its significant philosophical implications, prompted me to investigate related areas that were crucial to my understanding of the architectural phenomenon, including psychology, particularly the psychology of form, or Gestalt (as explored by authors such as Wertheimer, Koffka, Köhler, and Arnheim), physiology, art, and a specific branch of philosophy — phenomenology. The reason is clear: all these disciplines are closely tied to questions of perception. Aesthetics, as the theory of taste, is related to sensuous perception and beauty; therefore, I thought that by investigating the mechanisms of perception, I would improve my understanding of beauty and enhance the quality of my projects. So, I began investigating the relationships between various disciplinary fields, the mechanisms of perception, and architecture.

This conceptual choice had a major consequence: I began to shift my focus from the thing (i.e., architecture — facades, volumes, symmetries and rhythms of elements, etc.) to the subject, the perceiving body, which, as the inhabitant of architecture, is the subject of perceptions, the subject that perceives the thing (architecture or the physical objects that constitute the overall environment). This shift in focus meant I moved away from architecture as an external fact, controlled from above and the ‘outside’ (me/the architect/designer as a deus ex machina), towards the human body, the perceiving body, which is the ultimate inhabitant of architecture, the real ‘subject’ of architecture, acting, within architecture, from below, at the level of the things. At that moment, I was unaware that the perceiving subject could directly create architectures from the ground up, based on the record of traces left by its actions, movements, behaviours, and perceptions, much like a seismograph, a discovery I made later through the archi-textures. However, in one way or another, the shift in focus from the external perspective of the architect-designer (external agent of creation) to the internal experience of the architect-inhabitant (internal agent) had already implied that idea. In other words, there was a significant shift from an abstract, symbolic understanding of architecture to a more concrete, biologically-oriented one, focused on physiological and psychological factors in real-life experience and perception.

However, this was only the beginning of a process, and I was unclear about how to apply my new findings and readings to architectural projects. Although I still didn’t know, I now had a plan, which was most important. This had an inestimable value, which I didn’t fully appreciate it at the time, but having a plan, regardless of its specifics, gives past experiences, such as books read and things seen, and future endeavors or research a sense of unity and coherence. The plan acts as a catalyst or filter, selecting elements that fit its nature, thereby imparting a discernible, organic form. A coherence. This was the main ingredient my early projects lacked.

Among the many different books that I read during my theoretical detours (i.e., books which were not included in the bibliographies of the exams I had to take, but were included in my new custom-made ‘plan’), one had a significant impact on me: ‘Body, Memory and Architecture’ by Charles Moore and Kent Bloomer.[7] It resonated with me at the right moment, evoking memories of my childhood’s naive architectural experiences (which I mentioned earlier, see the article, On Architecture), as well as some intense experiences and bodily sensations I felt during my architectural tours across Europe as a student of architecture.

Gallery 2 (clockwise, Image 4, 5, 6): Dipoli, Espoo, FI, architects: Reima and Raili Pietilä (1961-1966), Renovation by ALA Architects. Photography by Toumas Uusheimo.

Gallery 3 (clockwise, Image 7, 8, 9): Max Planck Institute, Berlin, DE. Architects: Hermann Fehling und Daniel Gogel (1965–74).

Like many other books I’ve read on the importance of body and perception in architecture, that book reinforced my belief that exploring body and perception would provide a solid foundation for my architectural ideas and, as I soon discovered, a highly effective design approach by offering a key to decipher personal architectural experiences. To put it bluntly, I realized I needed to shift my focus from designing facades, window rhythms, pillars, and doors to how these architectural elements are perceived by the human body, making perception and the human body the central focus of the architectural phenomenon. It is the body that inhabits a certain space or place, the body of inhabitants that determines the arrangement of architectural elements (walls, windows, doors, floors, ceilings etc.) in that space or place, not the architect from his/her desk. This means that architects, before being designers, must be the first inhabitants of a space or place, the first that inhabit a space with their imagination, a space created by their imagination before all others can appropriate the product of their creation; in the first case the body acts like an active agent — an internal agent, I’ve said before — for designing a building; in the second case, it is a passive agent that will likely suffer the choices of the architect, from the outside and from above (i.e., from a desk, in a distant office).

1.1 The Turn from Matter to Body and Space

My customized bibliography, drawing from various disciplines related to aesthetics and informed by my personal experiences of perceiving buildings’ materiality and navigating their physical extensions, ultimately helped me understand the phenomenon of architecture by providing a key to assigning coherent meaning and order to the vast amount of information I had gathered until that moment. I finally found a framework that helped me distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information, based on the guiding idea that architecture is a perceptual experience that engages all the senses and bodily capabilities to navigate ‘space’, which allowed me to escape the overwhelming labyrinth of architectural theories, styles, opinions, and schools of thought. Following this framework would have allowed me to bridge the gap between abstract architectural concepts, such as words, drawings, and diagrams, and their realization into aesthetically pleasing architectures, engaging all the senses. Obviously, as I developed my alternative plan, my understanding of architecture grew alongside the academic courses I took at the Politecnico, leading to a new awareness of the architectural phenomenon.

Ultimately, I discovered a philosophical approach that could take account of my early architectural experiences and my new understanding gained from books, magazines, exams, and lessons. This approach not only acknowledged my interest in various artistic expressions, especially visual arts, but also helped me understand aesthetic phenomena; more importantly, its philosophical roots in the body and perception provided a solid theoretical foundation for knowledge in general—this approach was phenomenology. In brief, and almost literally, phenomenology is the study of that which appears in relation to the totality of the modes of perception of the body, while moving and experiencing the world around—the physical environment. Literally, ‘that which appears’ is the sense behind the term ‘phenomenon’ from the Greek root, phaínomai, a term deriving from the verb ‘phaino’, meaning ‘to become evident’, ‘to be brought forth into the light, ‘to come to view’, ‘to appear’.

For the sake of precision, I must emphasize a crucial aspect of the phenomenological procedure that precedes everything else: during a period of great confusion, my early encounter with Husserl’s phenomenology was critical, even before I realized the convergence between body, perception, physiology, psychology, aesthetics, and architecture. By employing Husserl’s phenomenological approach, I established a solid foundation for knowledge, initially, and subsequently, knowledge of architecture.[8] In fact, Husserl’s fundamental insight, that we must return to the things themselves as given in experience to establish a stable ground for (general) knowledge, was what sparked my subsequent interest in these arguments or specific disciplines. I thought that since the subjectivist, direct approach to reality is universal — based on bodily perception, allowing us to directly experience the world — I could apply the same principle to architecture, which is a part of reality. So, my early encounter with Husserl’s The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology was even more fundamental than all subsequent specific readings. However, before developing a viable architectural procedure or method, I had to study Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and various psychological and physiological readings, which enabled me to translate fundamental phenomenological insights about body and perception into the realm of architecture.

Phenomenology marked a significant turning point for me, as it shifted my perspective on architecture from focusing on the composition of elements like walls, roofs, and doors in plans and drawings to considering how our bodies interact with and perceive the physical environment. Through perception, we gain the fundamental information needed to understand the world/environment, and consequently, architecture, which is an integral part of it. In architectural terms, I had to consider the functions of a building according to the way the body physically moves in space between the objects, and its behaviour, since the body’s movements directly influence the spatial distribution of volumes or floor areas required for a building to function, such as the differences between a school, an office, and a house. Moreover, this also required me to consider the physical presence of the building, including the complex material configurations that enhance not only visual perception but also tactile, auditory, and olfactory experiences. For me, that marked another significant architectural breakthrough: shifting from a purely visual approach to architecture, focused on form and sight, to a more holistic understanding that considers the full range of bodily experiences and sensory perceptions.

From an architectural perspective, this new awareness brought a significant reward: I could directly link a building’s function, or utility, to its form, or beauty, through the body, as both function and form are ultimately rooted in the movements, actions, and perceptions of the body. On one hand, the configuration of spaces and areas is directly tied to the movements, actions, and behaviors of bodies, which all require a certain spatial budget (every action requires a spatial budget, a thing I also understood from three transversal sources: the Russian film director Sergej M. Ejzenstejn, after his pioneering studies on scenography — see image 12 in Back to the Origins of Space and Place; the pioneering studies on dance by Rudolf Laban — see image 13 in the same article; and the pioneering studies on proxemics by Edward T. Hall).[9] On the other hand, the physical elements of a building (walls, floors, doors, ceilings, windows, columns, facades, etc.) engage our senses, namely sight, smell/taste, touch, and hearing, when we move or rest in a building, highlighting the fundamental importance of physiological and psychological factors in architecture.

I ultimately realized that the materiality and spatiality of architecture are active entities that, along with me as the perceiving subject, contribute to shaping the physical environment, rather than being passive entities created by my external agency as the designing architect. This was a sort of inversion in the process of designing architecture: from a top-down to a bottom-up approach.[10] As a result, the architect’s role is transformed from creator to perceiver and user. To put it in more technical, phenomenological terms, the architect’s role shifts from being a separate subject to being one among many, united with other things in the world of life, i.e., in complete solidarity with the surrounding environment. This new understanding of buildings had a profound consequence for me: I came to focus on the silent, physical extension or circumambient flux that surrounds and connects everything – what we typically call ‘space’ – which, in architecture, includes my body and other solid bodies like floors, ceilings, walls, windows, trees, streets, fences… as it is through this unifying flux that materiality is conveyed, serving as a medium between matter and body. This fact entailed a further shift of focus for my research: from the body to space.

So, I wrote the word ‘SPACE’ in my notebook and then visited the Politecnico library to gather insights from various experts, including architects, physicists, artists, psychologists, physiologists, sociologists, anthropologists, philosophers, and geographers, in order to learn as much as possible about my new area of study: space–the medium between body and matter.[11]

Image 10: This passage, from one of my earliest notebooks dating back to my architecture student days, clearly asserts the crucial role of space in architecture: ‘Forget plans, elevations, and sections! It’s all about space – the space our bodies inhabit, and our relationship with the world!!!’

In the context of architecture, many prominent modern and contemporary architects, including notable critics and historians like Sigfried Giedion and Bruno Zevi, have stressed the importance of understanding architecture as a discipline of space (as discussed in the Appendix ‘Architecture as Art and Science of Space’ in the article On the Ambiguous Language of Space); however, there is a significant difference between simply understanding a concept and truly internalizing it, making it a core part of one’s research – a distinction I have personally experienced. Although I was familiar with the key works of those architects and critics on the spatial value of architecture, I didn’t truly absorb the message until I had a personal experience with ‘space’, which I’m about to share with you—an Eureka moment, or what psychologists call a peak experience.

There was a precise, illuminating moment in my life when everything suddenly fell into place. Certain readings and architectural experiences I had in the past suddenly clicked, like finding the right combination to assemble a puzzle, and I finally saw the complete picture without any need for further trial and error. I suspect an epiphany requires a combination of conscious and unconscious factors, but you must be prepared when it strikes. This is exactly what happened to me on a sunny day in late October, as I sat comfortably in a deck chair on the outdoor terrace of my old home, basking in the warm sun and crisp, clear air. It was a bit windy, early in the afternoon. As I watched the leaves dance in the air, carried by the wind, and the Brownian motes of the dust particles suspended in the air, illuminated by the interplay of shadows and lights filtering through the wooden pergola, I suddenly realized that the space surrounding me, often considered ’empty’, was actually not empty at all. On the contrary, I observed that the space around my body was an explosion of activity—a living, dynamic flux that surrounded everything, including me.

Image 11: Brownian motes of suspended particles in an indoor environment

I literally saw the space all around me as the medium that allowed particles and physical bodies to move and dance around in the air, enabling light, heat, sounds and odours to travel from one physical body to another at a distance; the volumetric extension surrounding me, that circumambient flux I felt I belonged to, was the medium that conjoined my perceiving body with the physical environment made of streets, walls, trees, etc., around me, conveying information to me that I interpreted as colours, form boundaries, textures, heat or cold, sounds, and scents. At that precise moment, I realized that that distance or extension was what provided physical continuity and a coherent unity to reality, allowing a unifying relationship between objects and subjects. For the first time, I envisioned reality as a physical continuum, a plenum, where everything was united by an invisible, continuous, and material flux that surrounded and penetrated all, forming a seamless unity that dissolved the boundaries between my body and the world around.[12] Through a kind of illuminating perceptual inversion, I began to perceive the invisible ‘glue’ or ‘flux’ – that is, the ‘space’ that conveys information and connects us to the world around – rather than just the physical forms of the things around me. It was as if I was gazing at a different world: the space between objects rather than the objects themselves.[13] The moment was fleeting, as long as the blink of an eye, but it was enough to reveal the true nature of what was surrounding me.[14]

Image 12: Things or space between things?

Immediately after that experience, I rushed into my home, sat at my desk, and started creating drawings or, better, negative drawings for the interior design project I was working on at the time. Inspired by the previous instantaneous perceptual inversion, I began drawing the space between and inside matter, rather than drawing lines to represent walls or objects (see Image 12, above; Image 13a, 13b, below; see also Image 89). Hundreds of parallel and intersecting black lines, one next to the other, on a white paper, like in a sort of Piranesi’s etching (an analogy that didn’t occur to me at the time).

Image 13a-13b: The Well, etching from the series: Imaginary Prisons, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778); Drawing, Pencil on paper, Alessandro Calvi Rollino (1994).

Similarly, on the ground plan, the blank spaces on the paper, amidst the ocean of black lines, could reveal the architectural sequences of walls, windows, doors, and objects. And most of all, while I was designing the space, I wasn’t focused on the form, color, or details of the walls, roof, and floor. Instead, I was thinking about the sensation I wanted to evoke through that space and how the bodies would move within it. I realized that sensation involves all senses, not just vision, and that space – as the continuum between and within solid bodies – is what truly matters. It’s through space that information is conveyed, making it the primary focus of architecture (space itself was the flux of information!). I had to put my focus on the information conveyed through space, and nothing else. In other words, walls (matter…) were subordinate to space and should be understood as a byproduct of it, rather than the other way around.[15] This was the valuable lesson I learned from that experience.

After that episode, I gained a deeper understanding of concepts that had previously eluded me, including the idea that architecture is a discipline of space, as architects and critics often discuss (see the Appendix in the article On the Ambiguous Language of Space). I must confess that it was in that precise moment, as I watched the nature of ‘space’ through the Brownian motes of particles on a windy and sunny late October day, that I, much like a novel Paul Klee on his way to Kairouan, had an immediate awareness to be an architect, independent of any degree or certification.[16] Ultimately, I had learned what ‘space’ was, by a direct, striking, illuminating experience.[17]

So, the next step in my research was to determine the type of information conveyed through space and, crucially, how to translate this new knowledge into coherent, interesting, and, possibly, beautiful architectural forms and spaces.

What kind of information is conveyed through the extensive continuum for architectural purposes? How can that information be translated into coherent and interesting architectural forms and spaces?

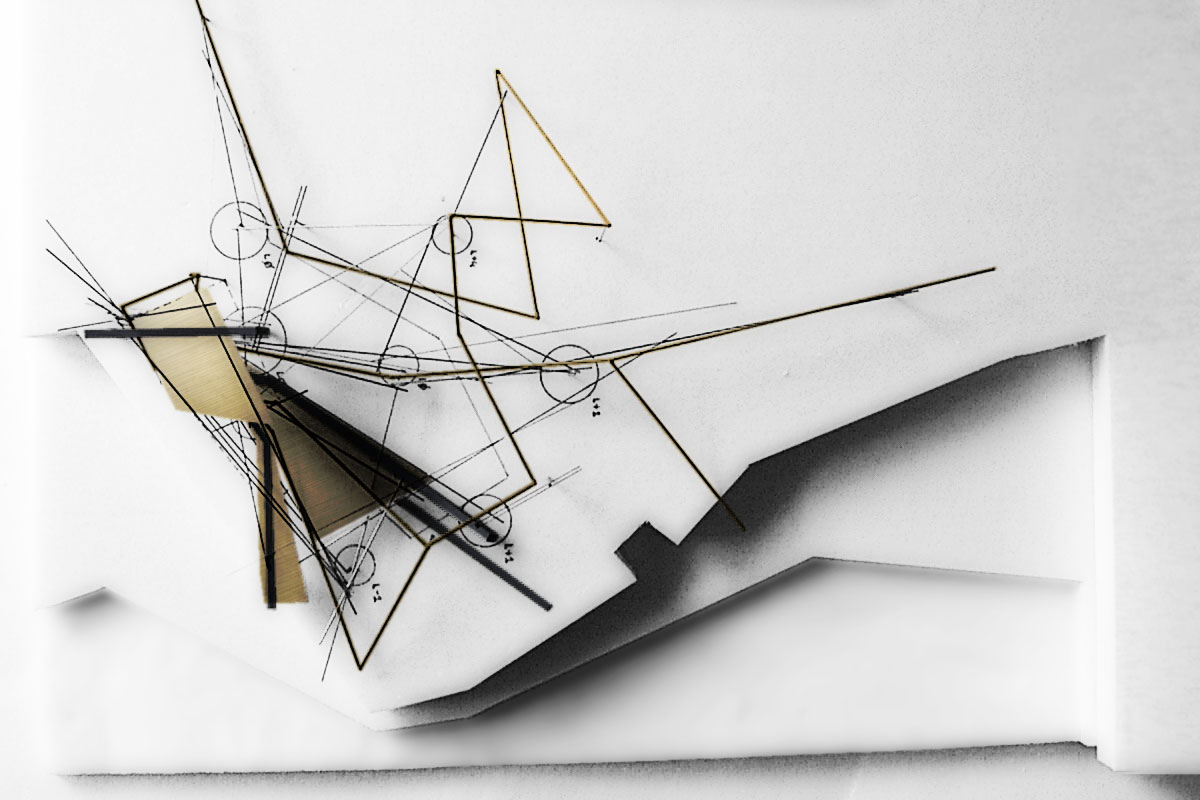

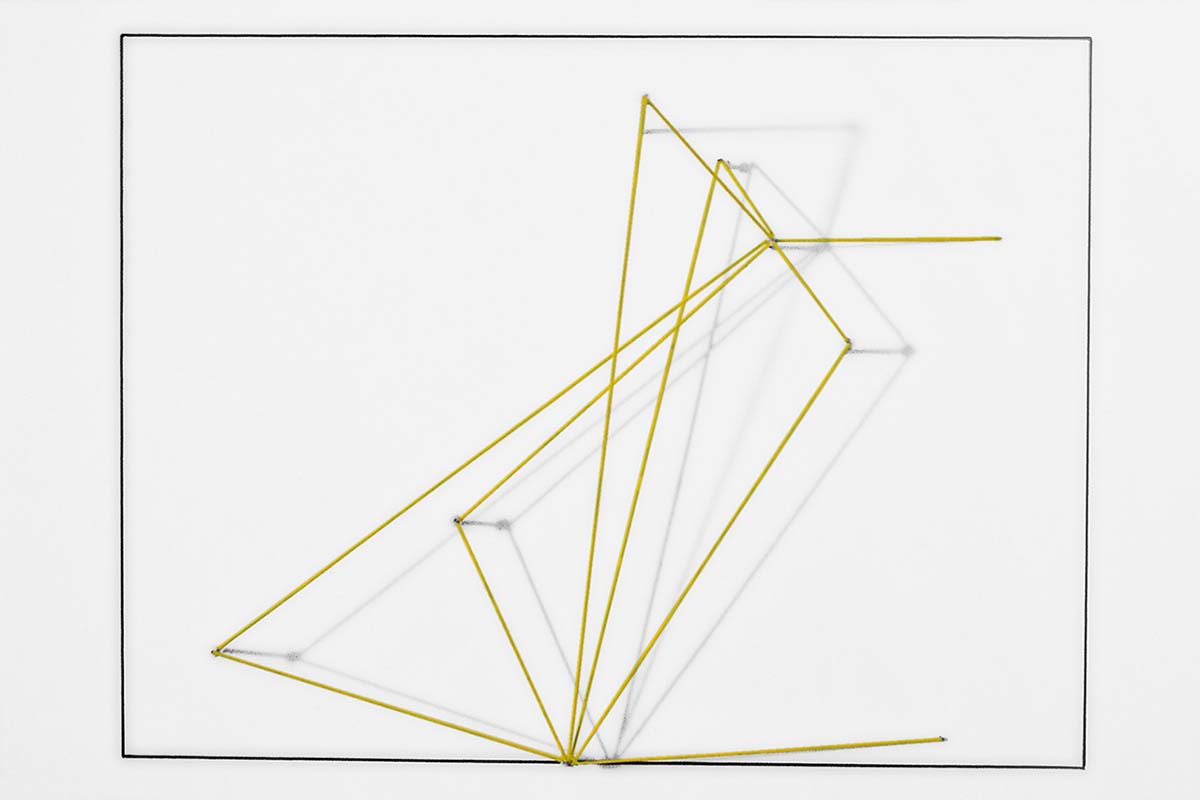

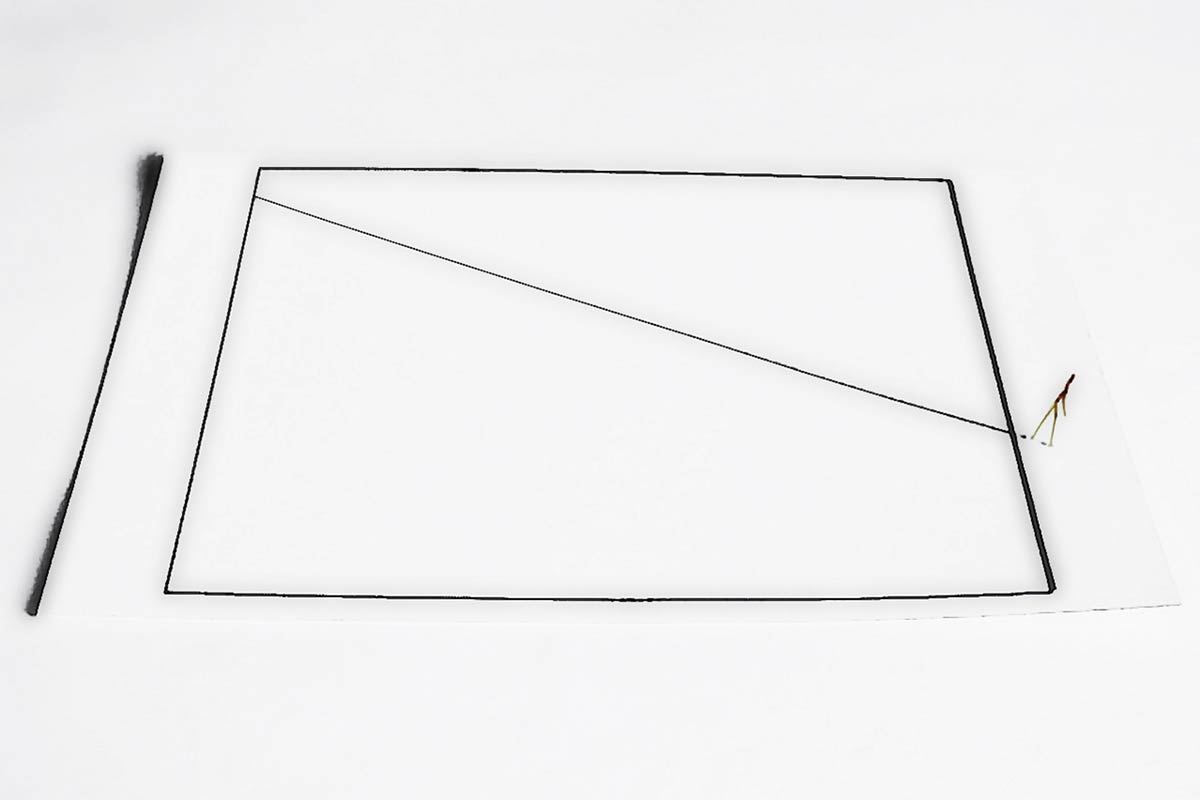

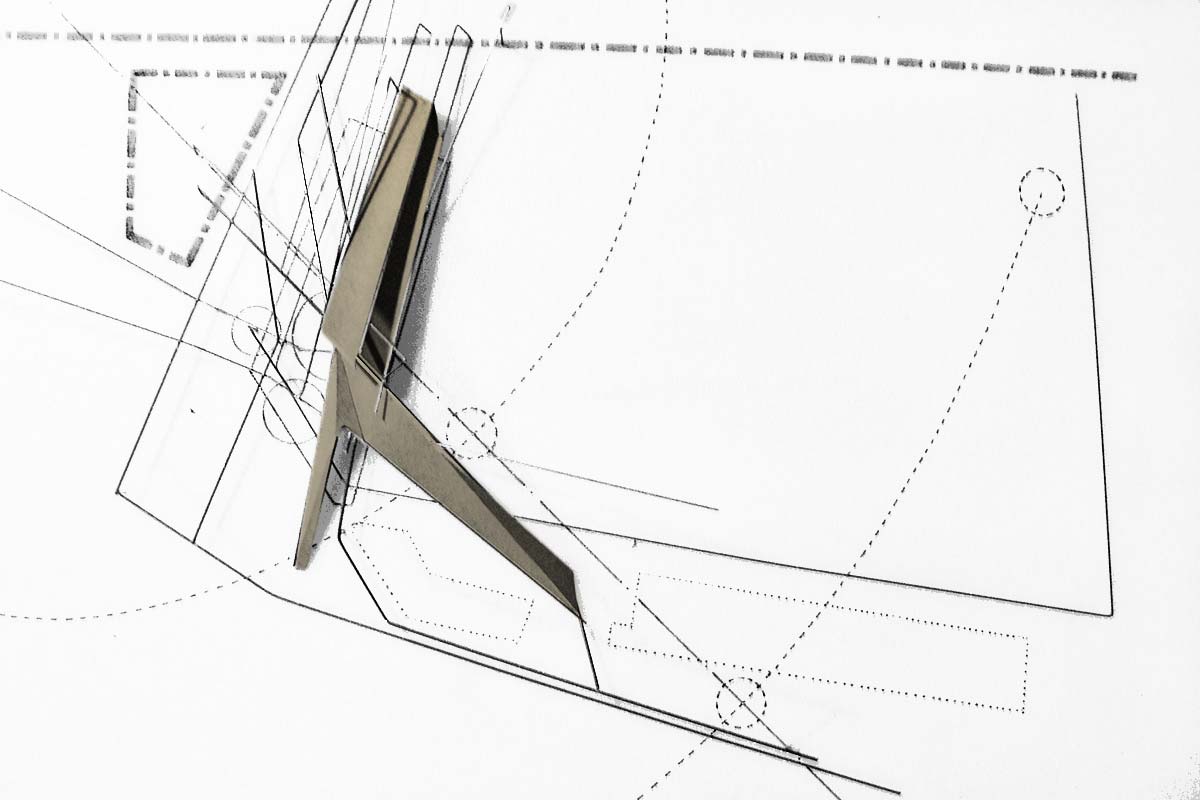

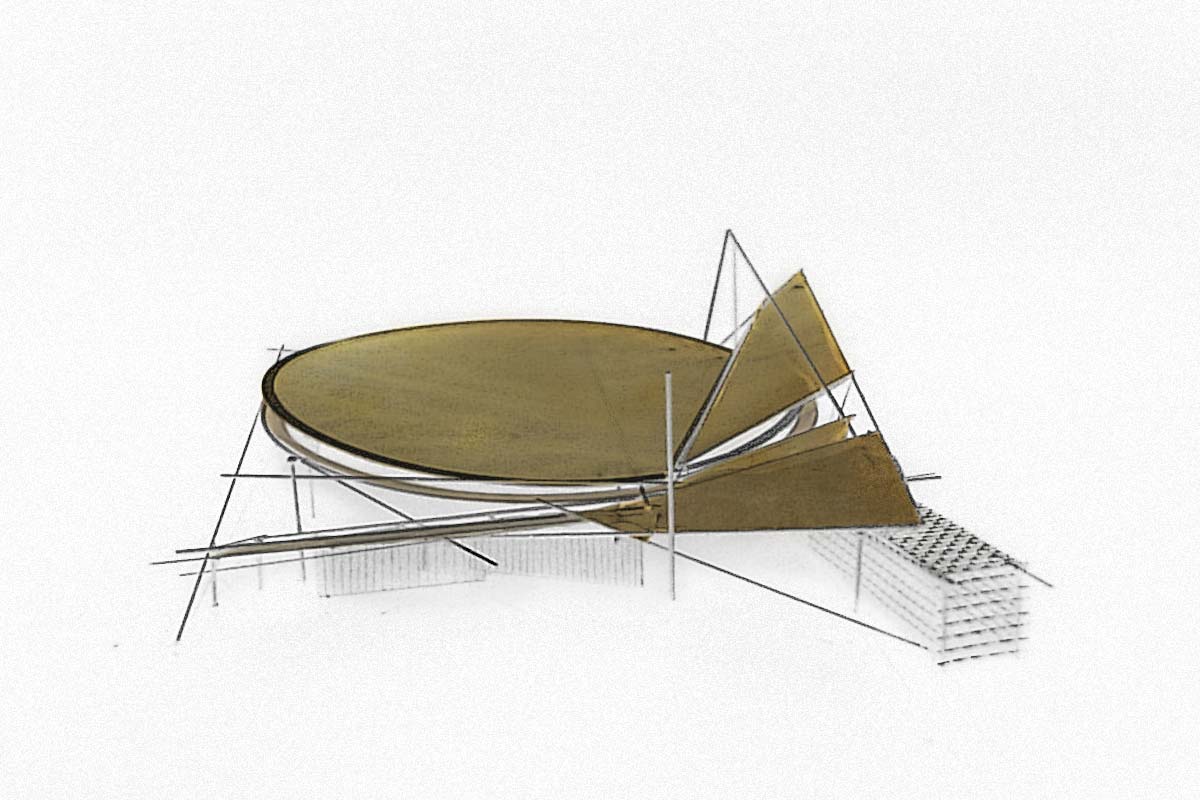

Image 14: Archi-texture, study model for a library in Legnano, IT, Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto (2009).

2. Archi-textures

Archi-textures represent vectorial forces of our physical presence in and sensory experience of specific situations and places.

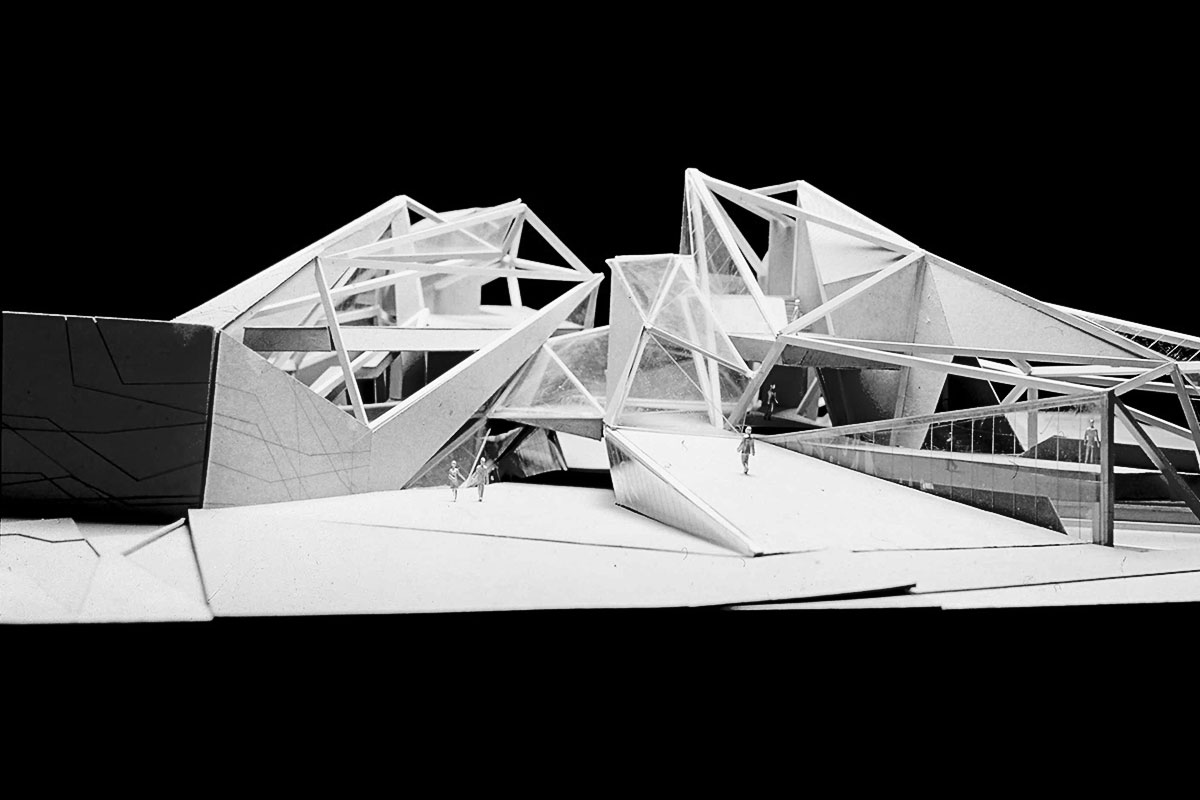

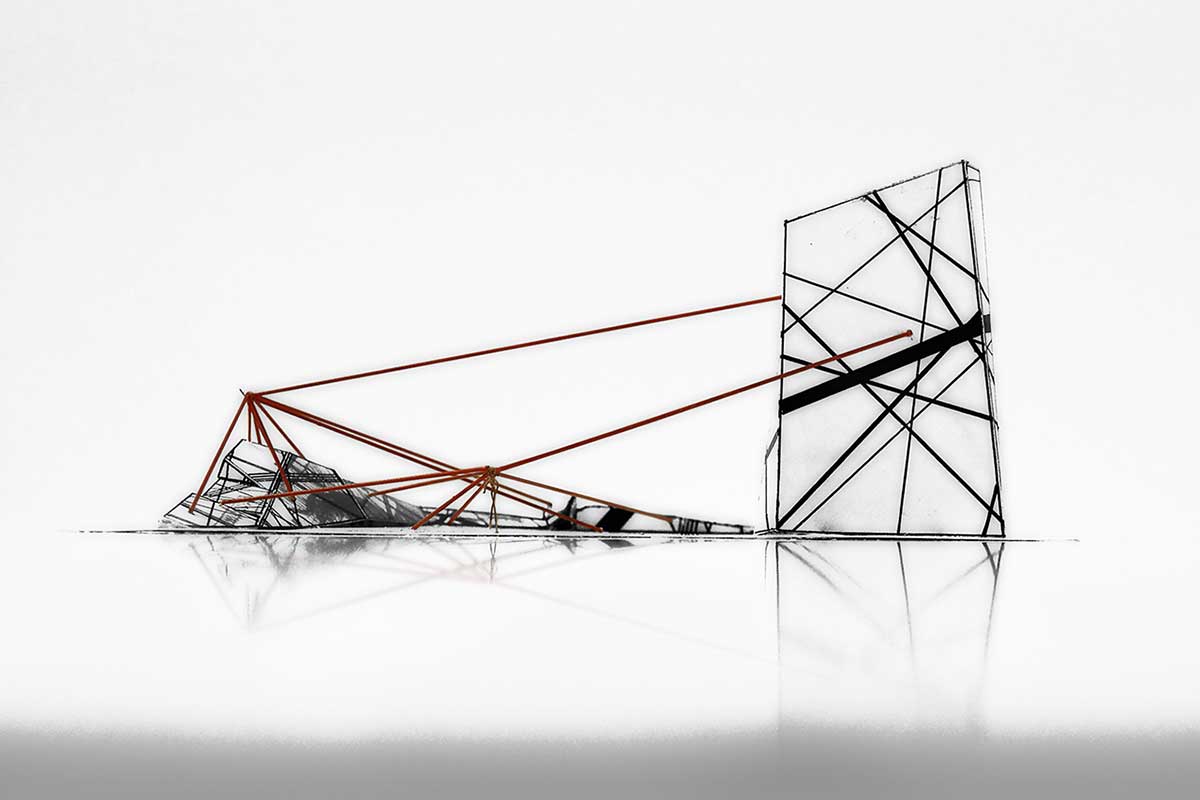

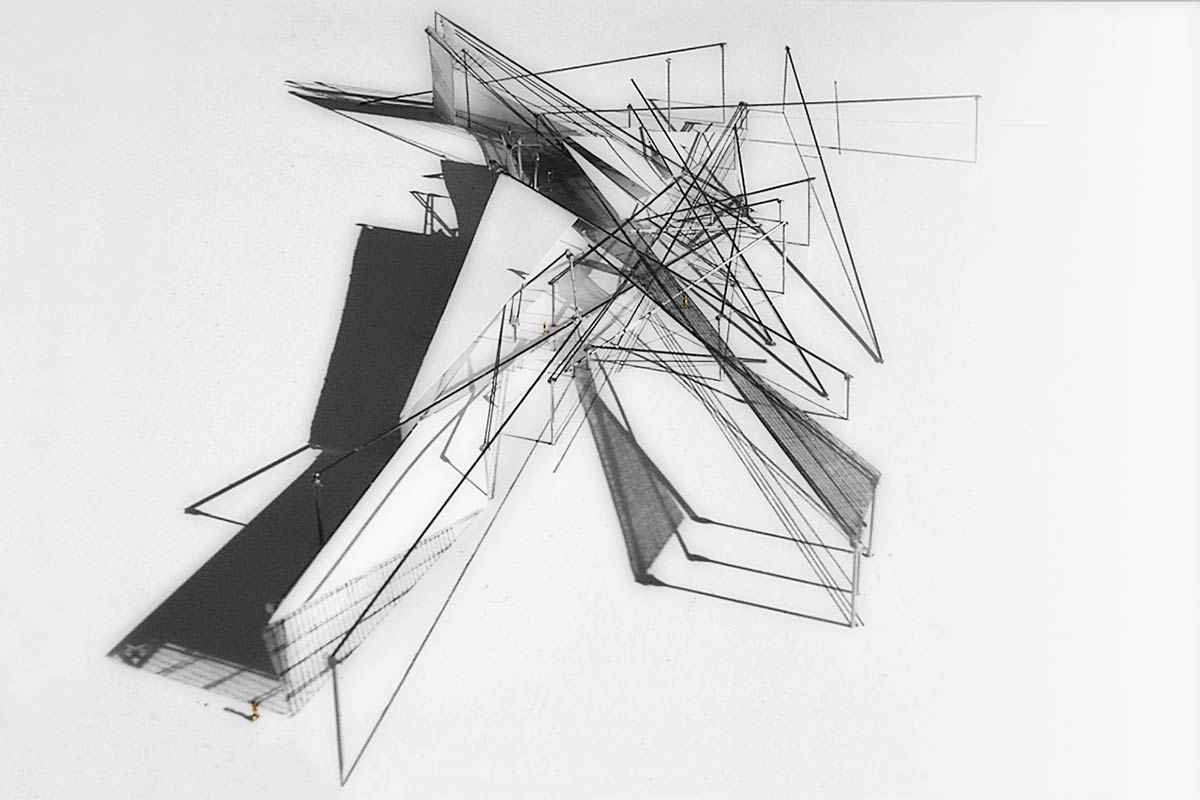

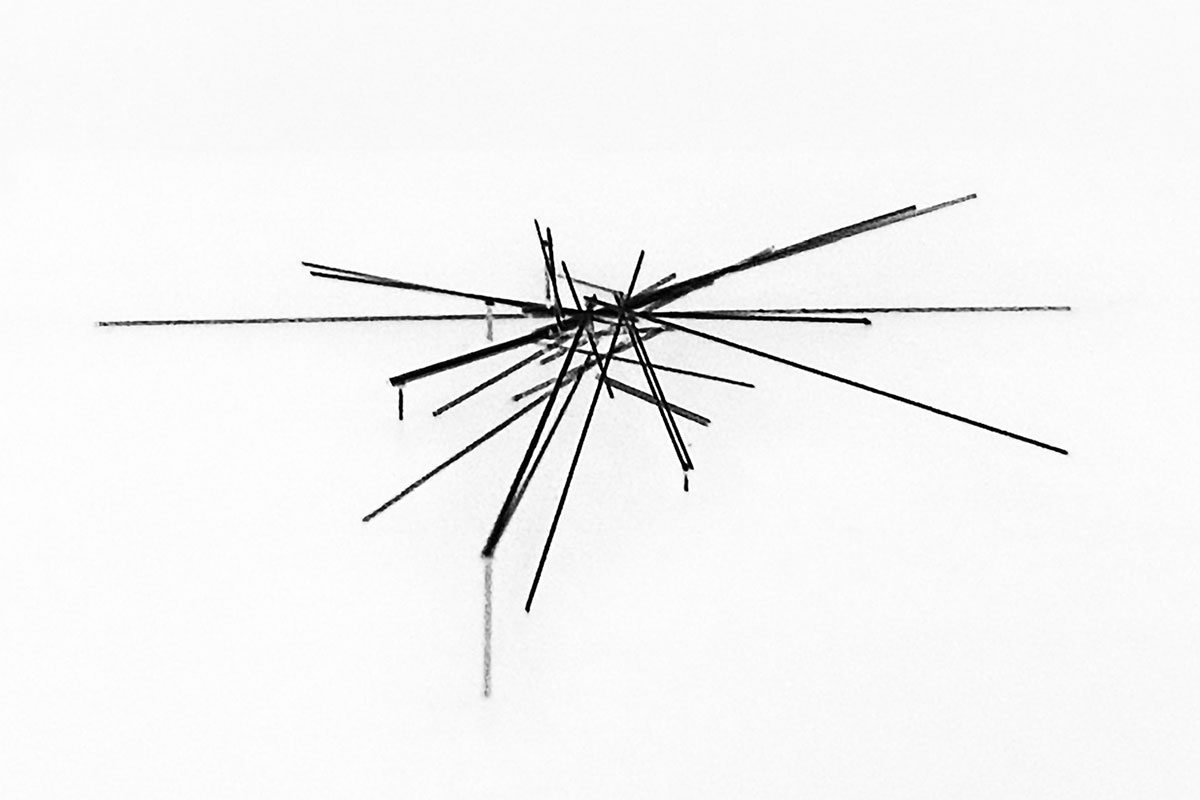

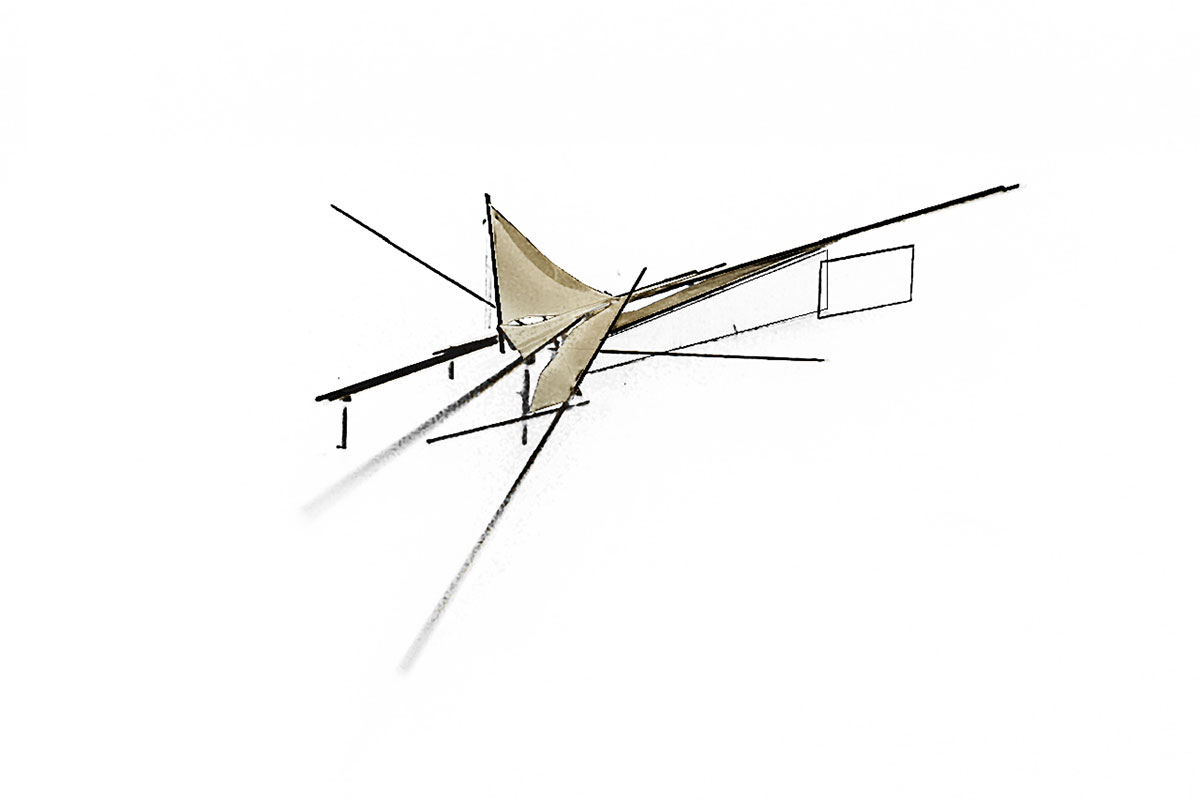

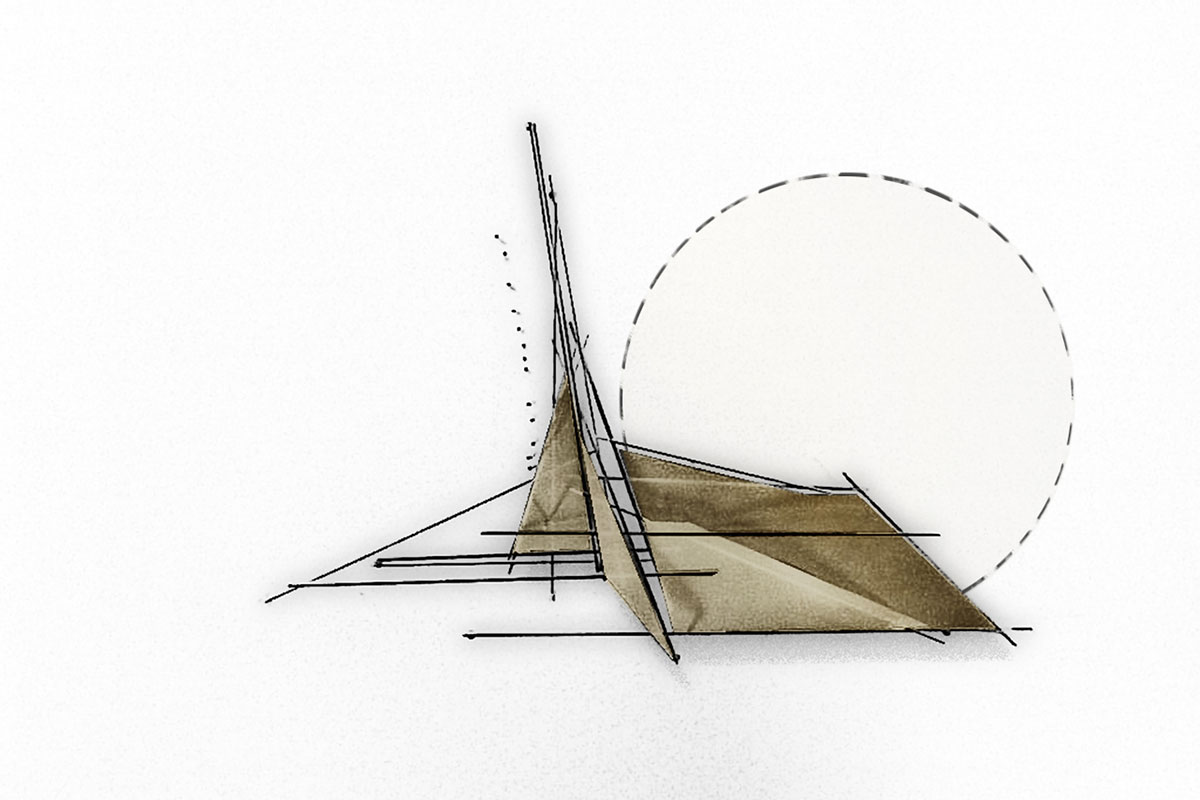

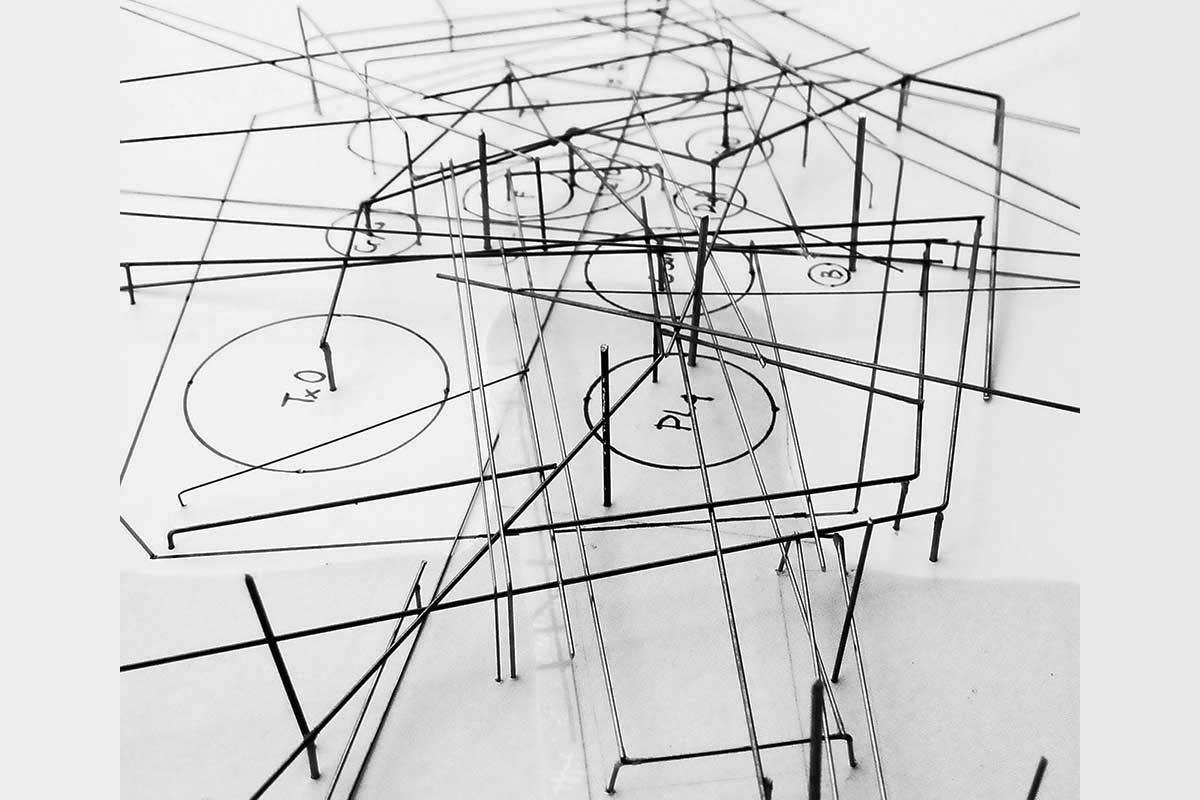

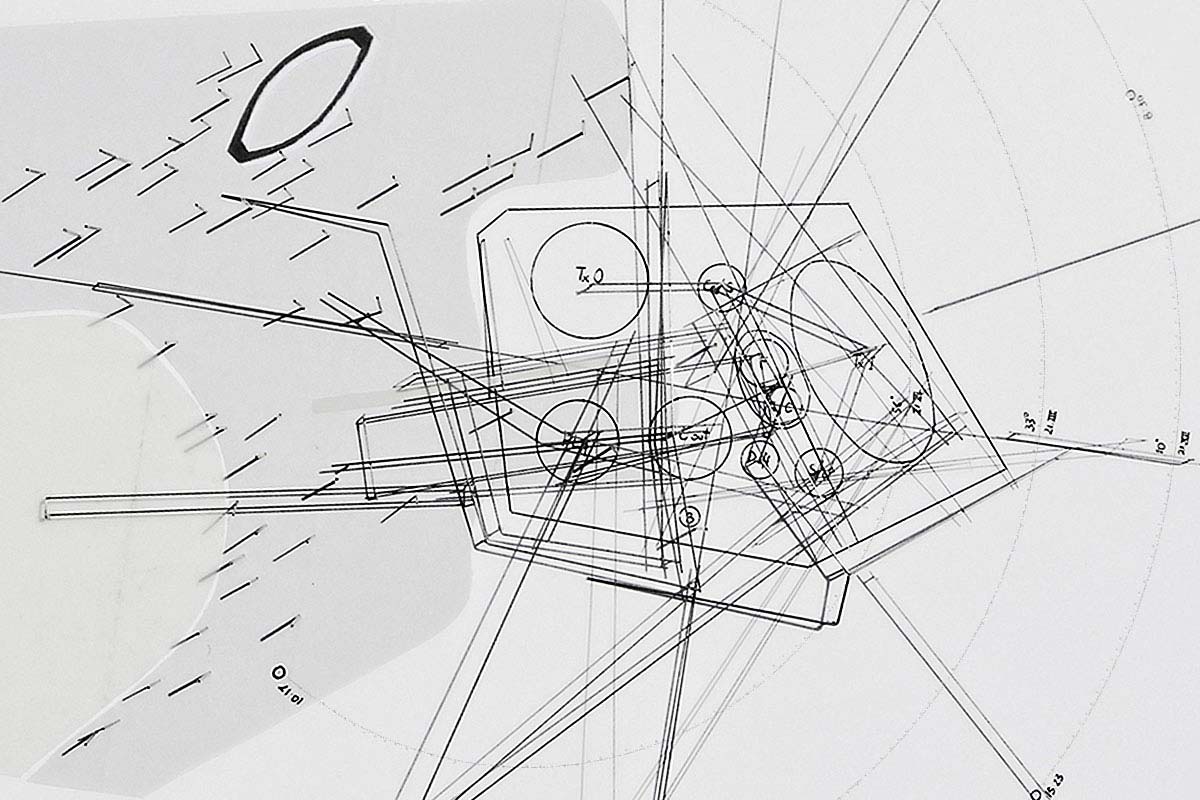

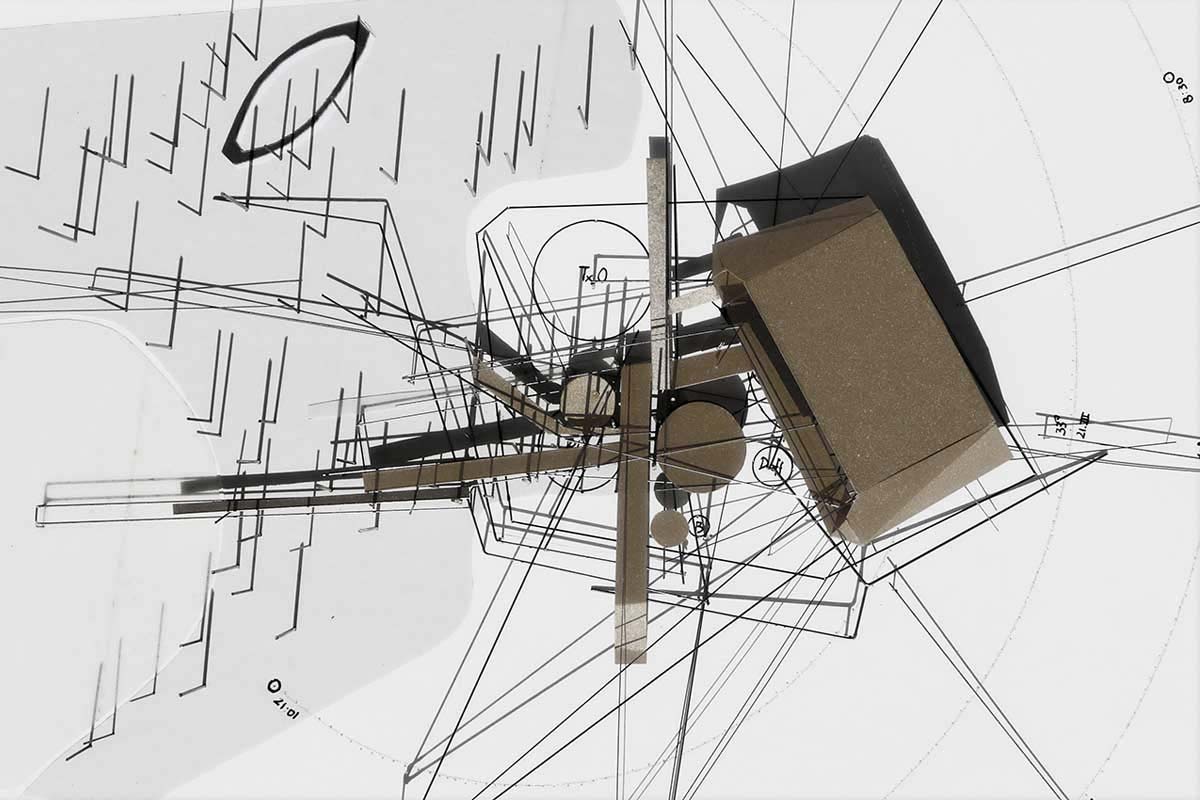

Coming back to the period when I was developing my new awareness of space and architecture, what mattered most to me was finally achieving a coherent unity of utility and beauty in my projects, after many efforts and little success. After I realized that architecture wasn’t just about creating physical forms and volumes by the architect as a deus ex machina, but rather about the exchange of information between the environment and the people in it, conveyed through space and time, I felt restricted by the traditional tools used to represent and produce architecture, such as technical drawings (with CAD design still in its infancy ) and models. ‘If architecture is a discipline that conveys information in space and time, between the subject and the physical environment, how can I visualize and translate this information and its inherent tetra-dimensionality into projects?’ Traditional drawings and models were not the solution; I was also dissatisfied with representing space solely through negative drawings, which I temporarily replaced with ‘positive’ white lines on black paper, where the black paper represented space. After all, my negative drawings only allowed me to visualize a generic space as a physical extension, but not the specific perceptual information, such as visual, auditory, olfactory, haptic, or tactile cues, that is conveyed through space and exchanged between bodies and objects, whether they are volumes or surfaces. So, I began to think that I needed to find a true four-dimensional counterpart to my early negative drawings, reminiscent of Piranesi’s style. How could I represent my understanding of physical reality as a ‘plenum’ in spatial terms–a ‘plenum’, an all-encompassing physical continuum as the medium for the actions of bodies, including the movements of people and their kinesthetic experiences, as well as the exchange of perceptual information between bodies and the physical world, encompassing visual, auditory, tactile, haptic, and olfactory information? It took me a couple of years of intense interdisciplinary research, which I later expanded to include physics and topology to explore the phenomenon of space from diverse perspectives, before I could finally develop a coherent architectural answer – a ground-up design approach that I termed ‘archi-textures’, a concept I discovered later while reading Henry Lefebvre’s The Production of Space, after completing my degree.[18] Broadly speaking, ‘archi-textures’ are peculiar four-dimensional models that enabled me to represent space, tracking the movements of people, and tracing their exchange of information with the physical environment, including their perception of the surrounding context.

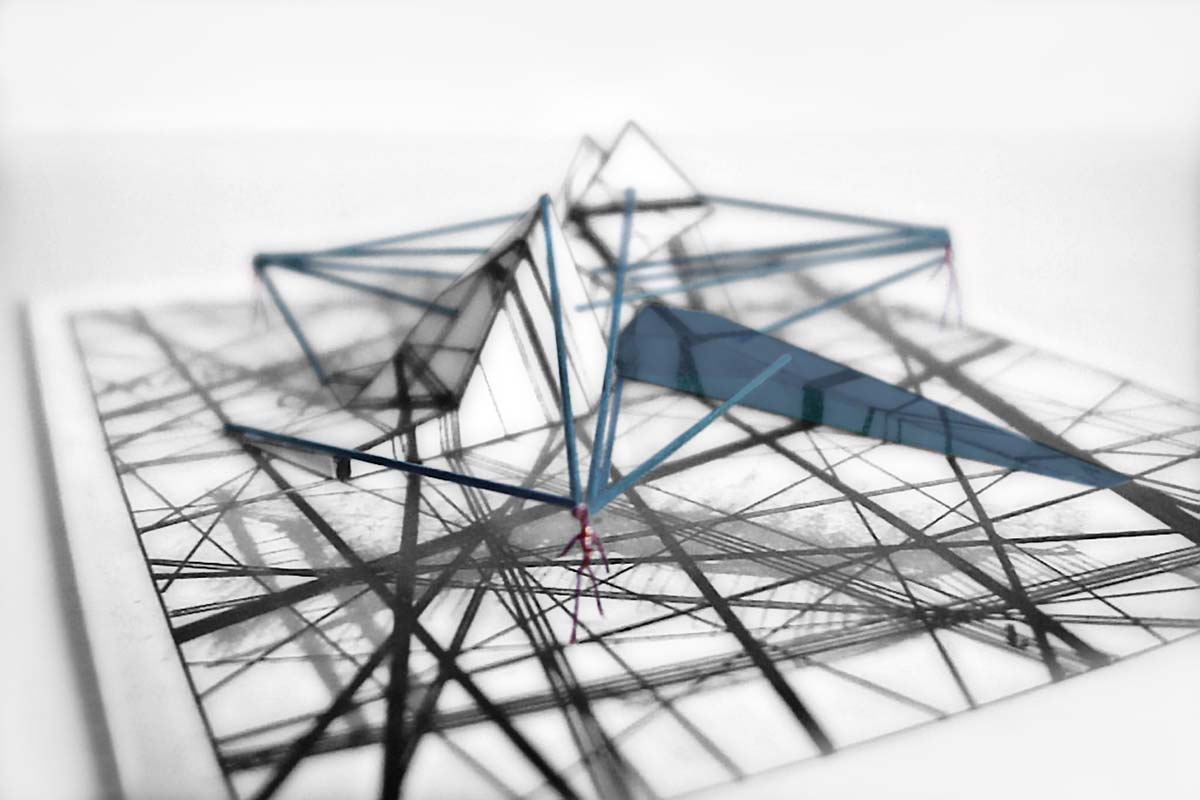

Archi-textures are four-dimensional models that represent space by tracking people’s movements and their sensory perceptions of the physical environment, including visual, auditory, olfactory, and tactile or haptic spheres of perception. This is the metaphysical and physical backbone (hypokéimenon) for the emergence of architectural space, providing topological direction and differentiation to the environment before geometric and architectural considerations come into play.

Regarding those models, I used the term ‘four-dimensional’ instead of three-dimensional to emphasize that the temporal factor was essential for architecture, as the human body, the true creator of the architectural phenomenon, moves around and perceives the physical environment, creating spatial and temporal sequences simultaneously. These models were not designed to showcase the finished project or architectural idea, regardless of how defined or undefined it was; rather, they reified the sequences of people moving and perceiving space through their senses and kinesthesis. The sequences of movements and perception, expressed through materials like cotton threads, spaghetti, metallic wires, or 2D lines, created the project’s space. During the construction process, the model itself generated the idea of the project or the architectural concept to be developed into a definite form, not the other way around. When I drew a line or stretched a cotton thread from a pin to another, it represented people’s movements and various sequences of visual, auditory, olfactory, and tactile or haptic perceptions – actions, behaviors, and perceptions that occur in and through time and space. This is why I referred to four-dimensionality: primarily, those models were processual models, representing processes by way of lines in space as fields of perceptions, movements, and so on. These are not representative models, meaning they do not represent actual architectural forms. These models represented a realm of potentiality, containing various possible architectural forms or configurations that could be developed through certain processes, but not others, depending on the architect’s choice, sensibility and available data (social, historical, technological, economic, etc.). This was before the realm of actuality, where architecture – or the model of architecture, for the case – had already taken on definite forms (for more on how these processual models, or archi-textures, can give rise to an architectural form, see the video Chōra)

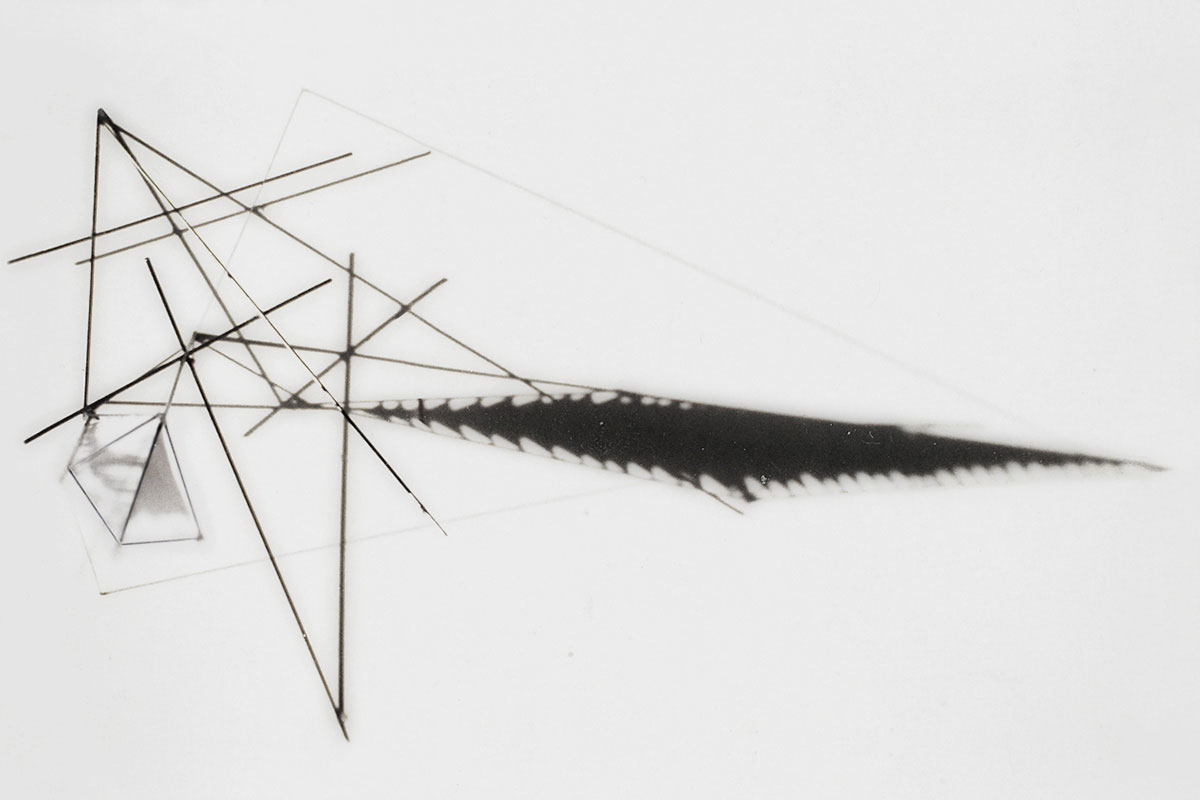

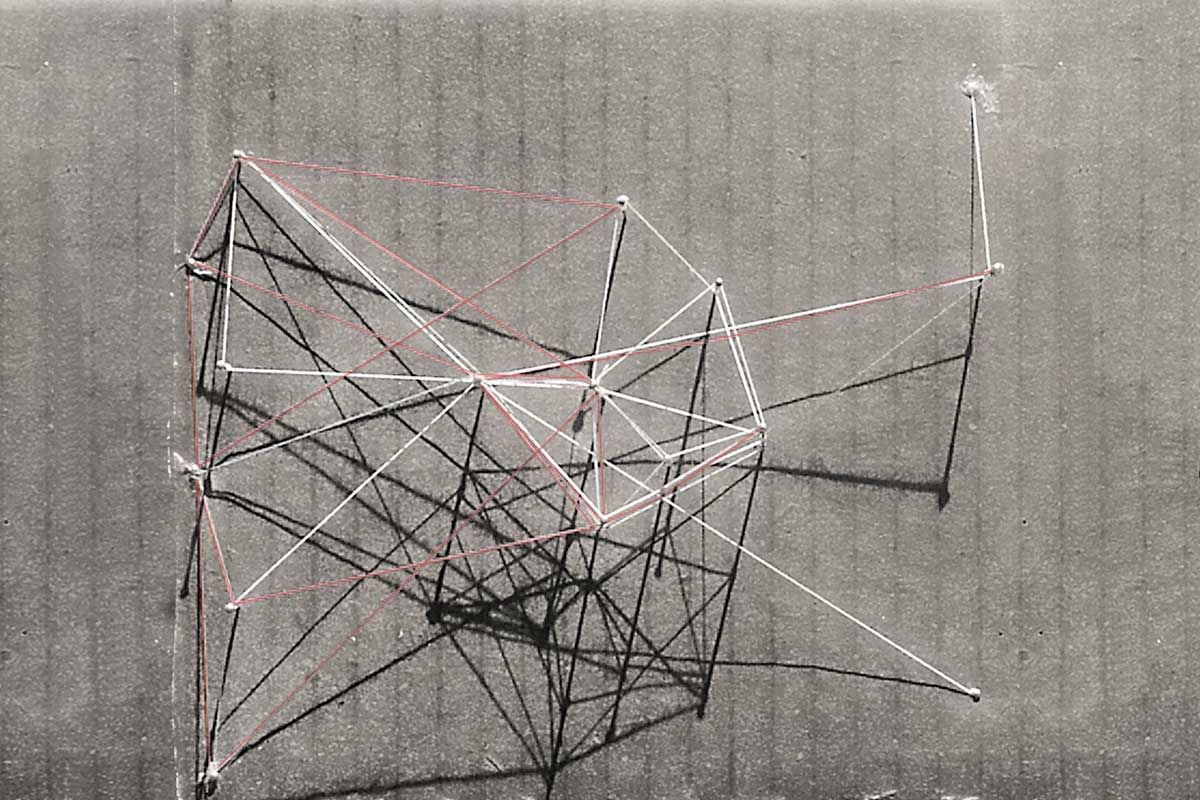

Image 15: Archi-textures evolved from four-dimensional, processual models that represent subjects’ movements and perceptions in and through space and time. The model above, which represents one of the techniques I also used for producing my archi-textures, is by Andreas Mavrakis: Tensile Overhead Plane Architectural Concept.

To avoid basing project reasoning on two-dimensional drawings, I opted to create a ‘dimensional upgrade’ by using actual 3D drawings that represented people’s movements and perceptions. These archi-textures connected everything within a primordial environment, eliminating the division between perceiving subjects and objects, and leaving only relations. This created a metaphysical environment where relations were reified by cotton threads or thin metallic wires floating in 3D space, rather than two-dimensional lines on paper. I used two-dimensional drawings only for diagrams, and later in the design process, when the architectural form was already established in its main topological terms, I employed sections and plans. By focusing on space as the core of architectural activity, I inverted the traditional procedure by reasoning directly from 3D models, considering the temporal aspect intrinsic to archi-textures. I believed that starting with two-dimensional representations would limit my understanding of the surrounding environment, so I directly began thinking in three/four dimensions using archi-textures.

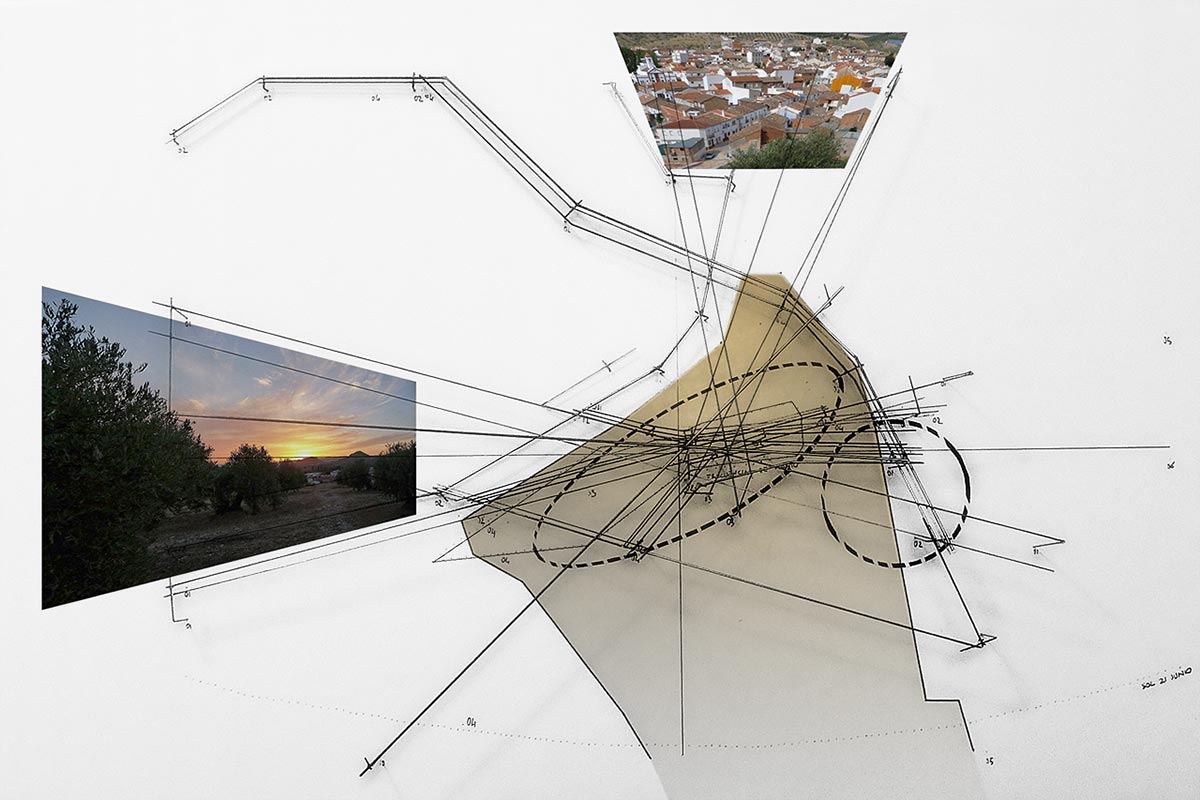

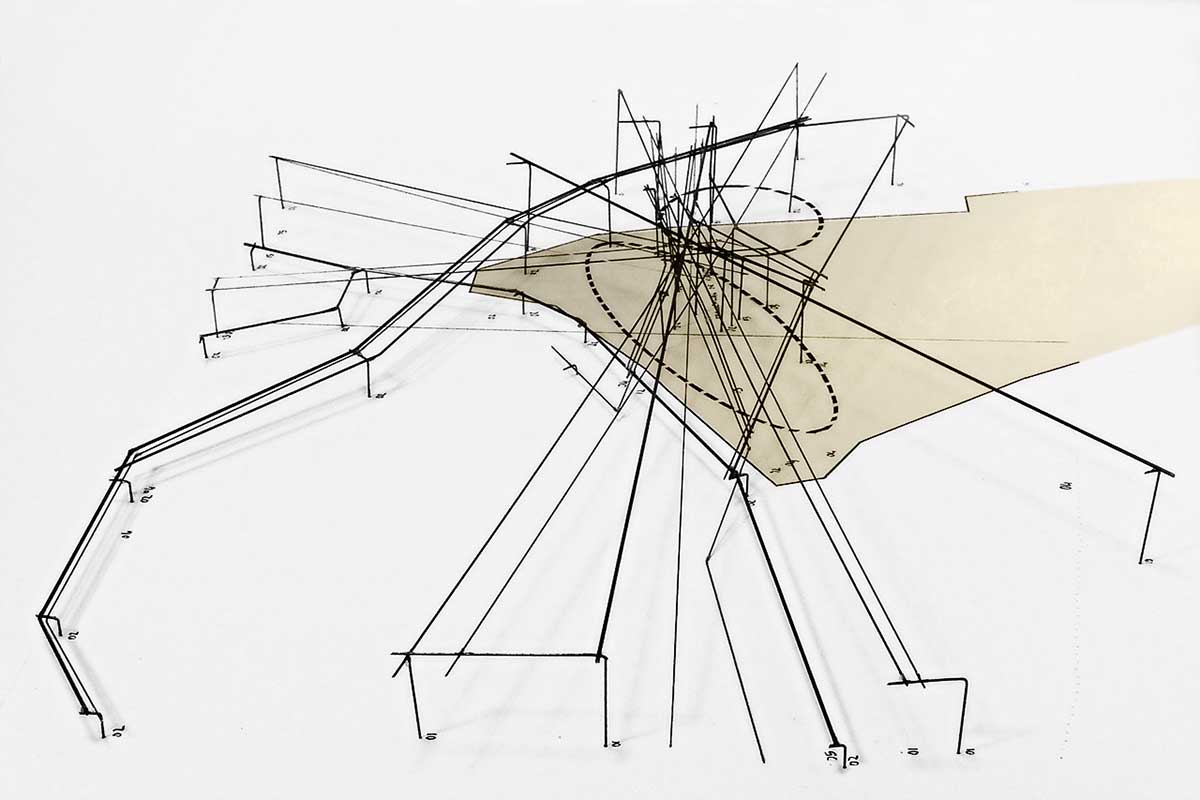

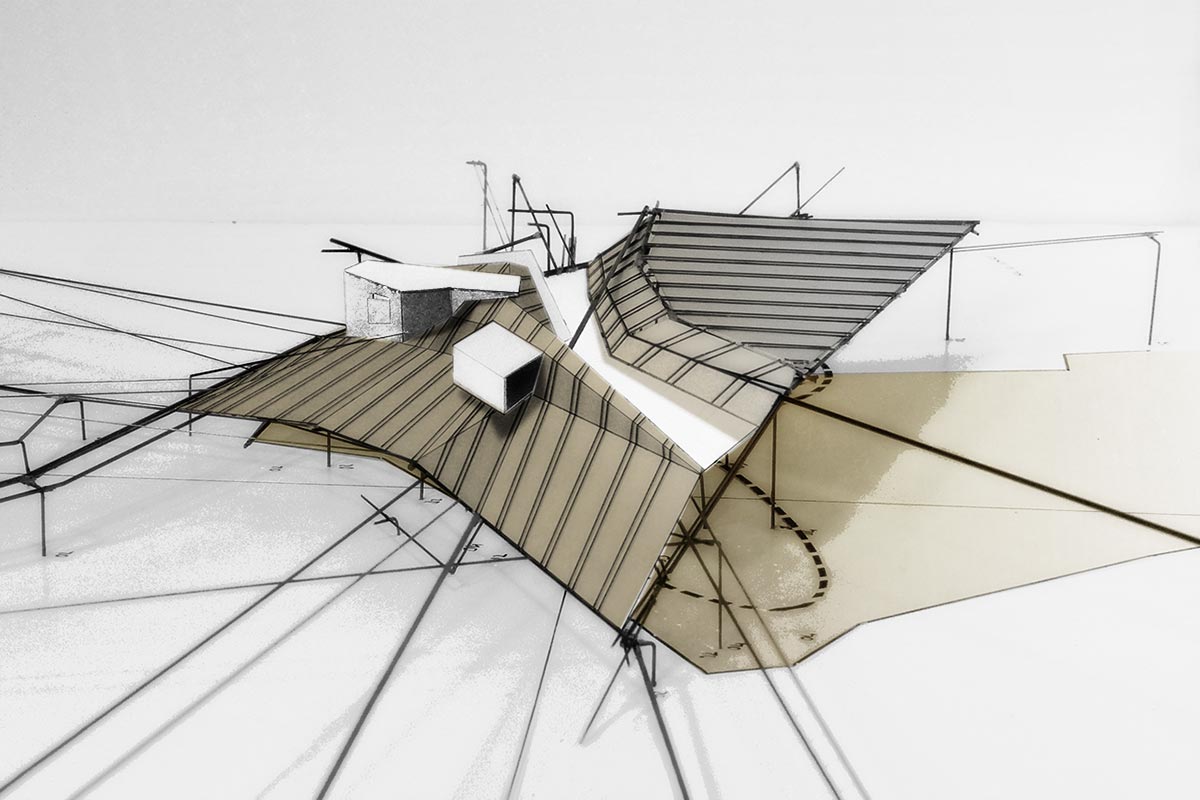

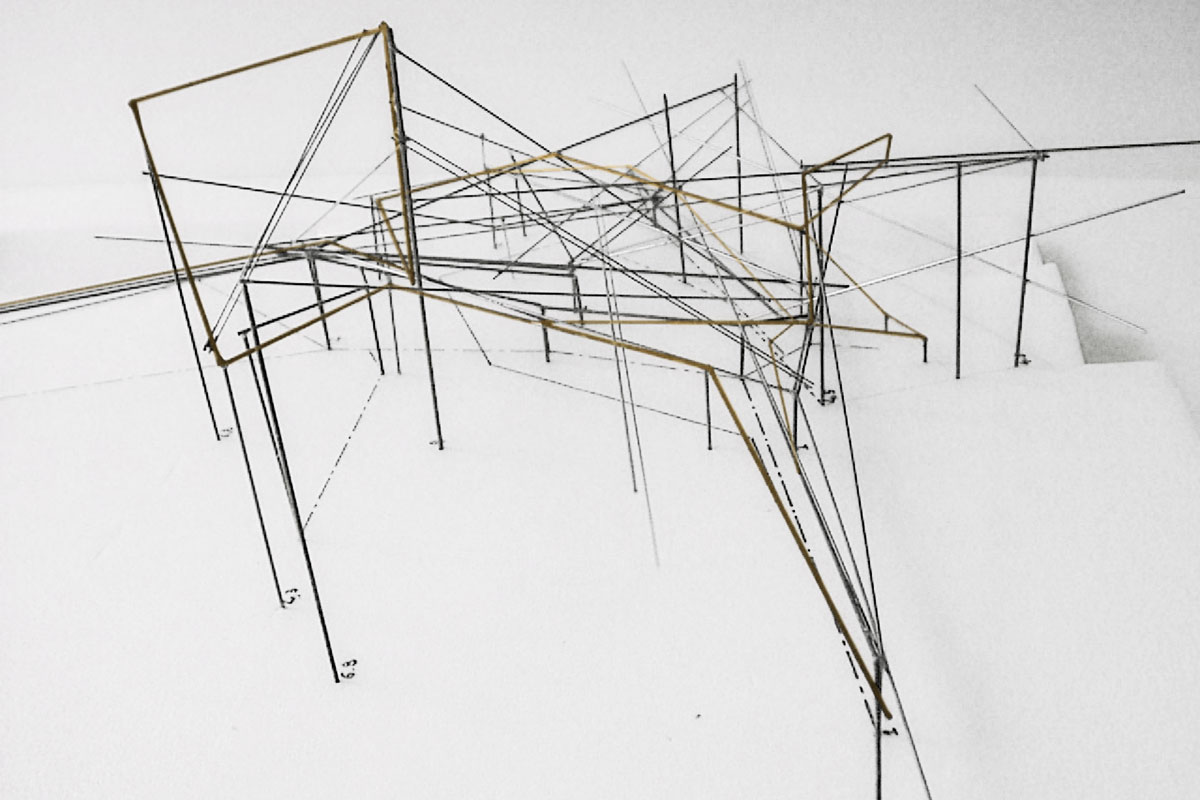

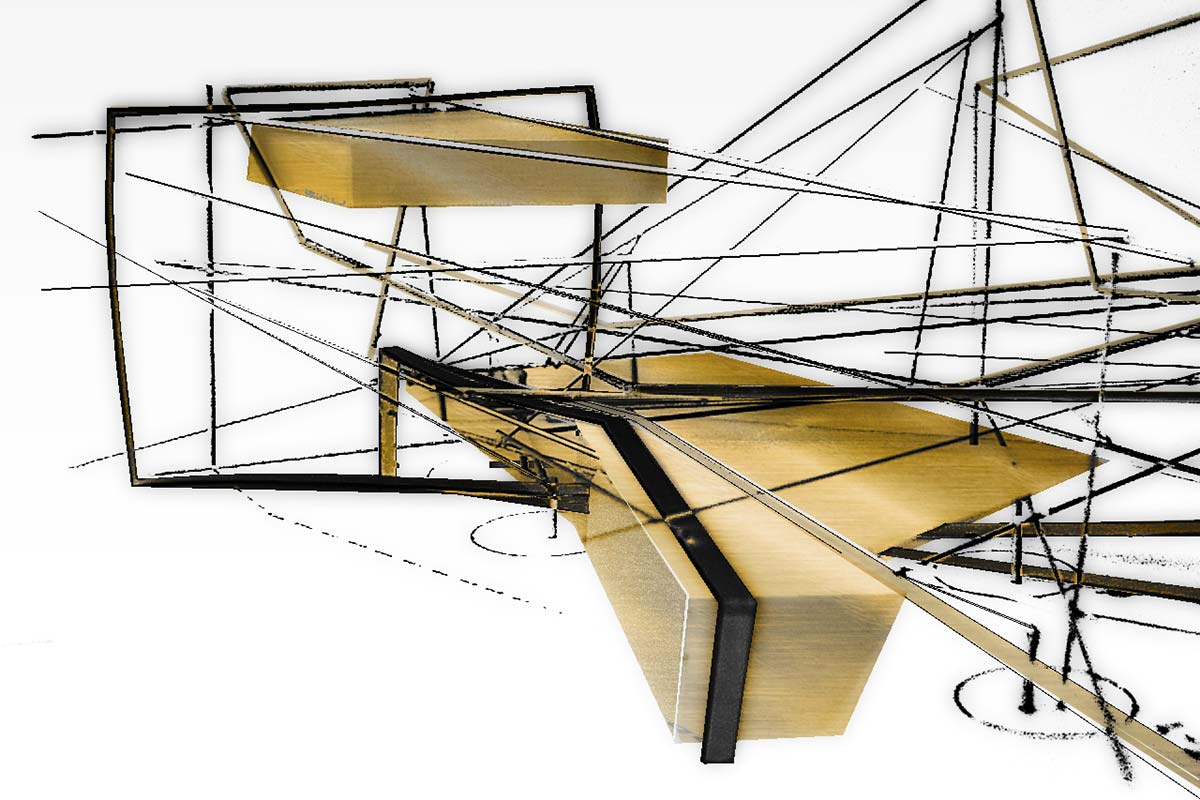

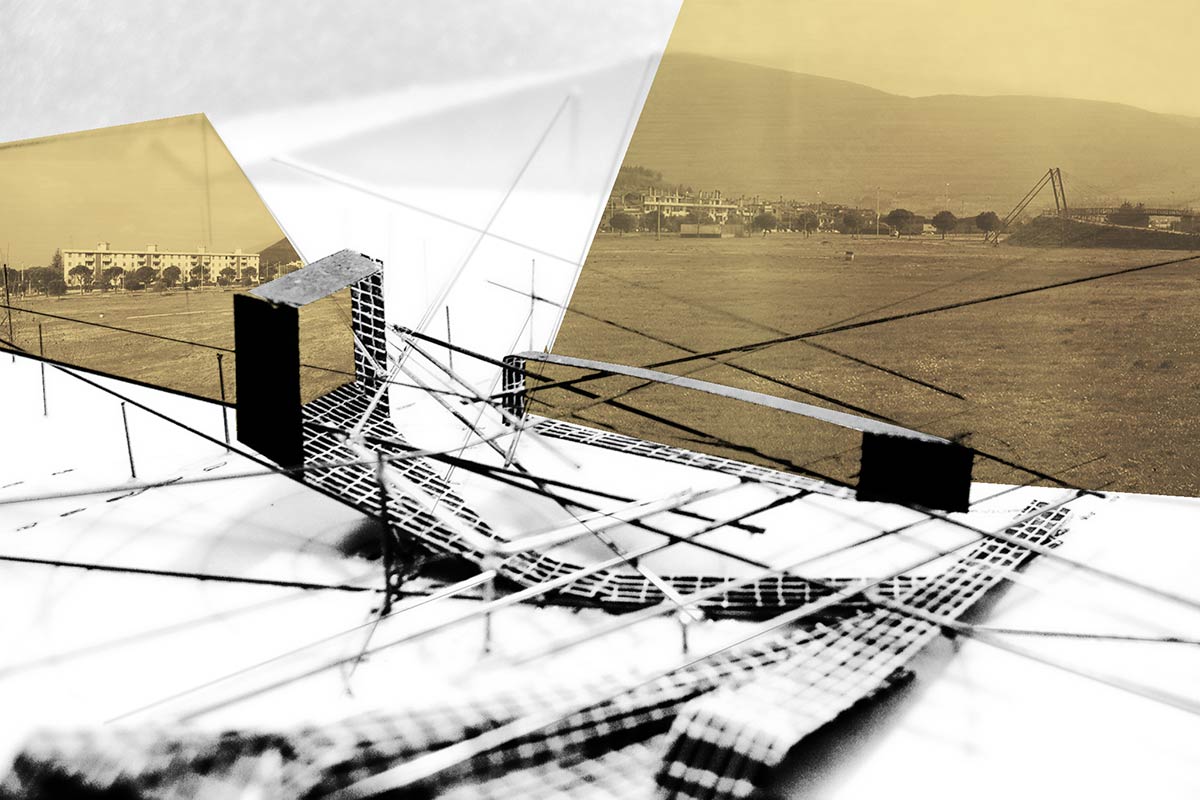

Slideshow 1 (Images 16-19): Archi-textures, study models and final rendering for the Ydañez Museum, in Puente de Genave, ES, by Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto, in collaboration with architect Sandro Panarese, 2011. Project shortlisted for the World Architecture Community Awards, 2011; published in the book Creative Diagram In Architecture (Beijing: IfengSpace), 2012.

One advantage of archi-textures was that they enabled me to represent and specify the type of information exchanged between the human body and the physical environment, including movements, visual, auditory, haptic, and olfactive perceptions, in the context of a project, taking into account the actual place, including streets, buildings, trees, the sun’s path, winds, and actual environmental sources of stimuli. Ultimately, I used archi-textures to represent and visualize space through physical models, which allowed architecture to emerge through a continuous process of refinement: model after model, it seemed that space could give rise to matter, or architecture, in the form of walls, roofs, floors, balconies, and so on. Similar to the collision chamber of the Large Hadron Collider, where subatomic particles’ tracks are visualized after a collision, these models enabled me to visualize what is usually invisible to the naked eye: the paths people leave behind as they move through space, as well as the perceptual fields that connect people to the physical environment, including lines of sight towards specific objects, buildings, or landscape features; sources of noise symbolically represented by wires; and sources of tactile or olfactory stimuli that connect the body to their sources, such as fragrant plants, the sun’s path, or cold winds from a certain direction. In this way, I could instantly visualize and decide which aspect of the physical environment to emphasize or downplay in the relationship between a body and its surroundings when designing architecture.[19] By using wires or threads, I was eliminating the distance between the perceiving subject and objects, including the physical environment and buildings, demonstrating that they are inseparably connected: the perceiving subject is one with the external world, and, similarly, the building is one with the landscape. A unified whole. Based on this awareness, more than a decade later, I would come to define the entire realm of existence – the unified whole – as a place, and to think that we are all places, fundamentally, a place of processes. Archi-textures were the sign of that fundamental solidarity among all existents, but, at that time, I still didn’t know that. This awareness ultimately led me to hypothesize a solidarity between humans and the world based on ecological principles, causing me to shift my focus from space to place. But that’s the end of the story, and there are many important steps missing before I could reach those conclusions, which I’ll revisit in the concluding paragraph.

Slideshow 2 (Images 20-24): Archi-textures, study models and final renderings for a Cultural Center in Bergamo, IT, by Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto, in collaboration with architect Sandro Panarese, 2004.

2.1 The Art of Occupying Space

How did I arrive at envisioning the spatial language of archi-textures? We are now entering the realm of what I previously referred to as qualitative determinants concerning the nature of things. Devising those models was a laborious process that took a few steps and a couple of years, even after I had identified 1) space as the main subject of architecture, after my epiphany with space. Other crucial steps were necessary: 2) identifying the motion of bodies (i.e., people’s movements), their behaviours and actions as the basic generators of space. Regarding this point, in one of my notebooks, I wrote: ‘In order for a design to be space-oriented, you need to think about actions’ — which I referred to as the ‘PRIMARY PHASE’, emphasizing the fundamental importance of the sequence: ‘body> behaviour> action> movement> space> architecture’. This issue is directly related to the ‘function’ or ‘programme’ of architecture, which involves the thoughtful disposition or arrangement of spaces based on activity diagrams to meet a building’s different functional requirements; 3) identifying the work of artists and architects that explored, either visibly or theoretically, questions of space and perception. In my notebooks, I formalized this issue under the proposition ‘L’ARTE DI OCCUPARE LO SPAZIO’ — ‘THE ART OF OCCUPYING SPACE’ (see Image 33, below); concerning this point, the experience of the Bauhaus school, particularly the theoretical and practical works of Gropius, Kandinsky, Klee, and Moholy-Nagy, significantly influenced my thinking; 4) implementing specific perceptual information exchanged between bodies and the physical environment into physical models, attributing space a material consistency by reifying the process of perception through lines, wires, threads, surfaces, etc. This crucial step resulted from my epiphany with space, which I understood as a plenum/continuum rather than an extensive void. Finally, 5) I organized the spatial information obtained based on topological considerations, recognizing topological space as the trait d’union between perceptual space and architectural/geometrical space.

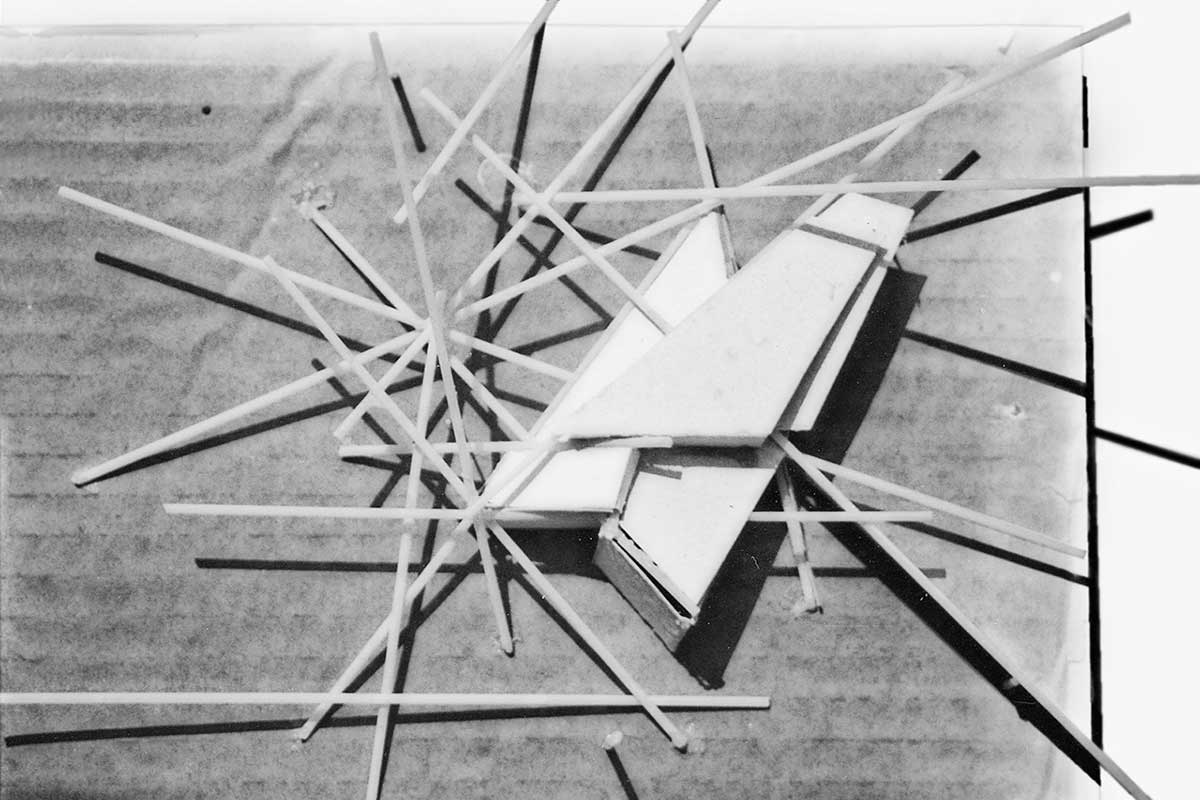

Slideshow 3 (Images 25-27): Primitive forms of archi-textures in-between art and architecture: these models had ‘space’ as their conceptual motor (c. 1994). Once I could integrate people’s movements (Slideshows 4 and 12) and perceptions (Slideshows 7 to 11) into an organic whole, the spatial value of those models evolved into the mature language of archi-textures.

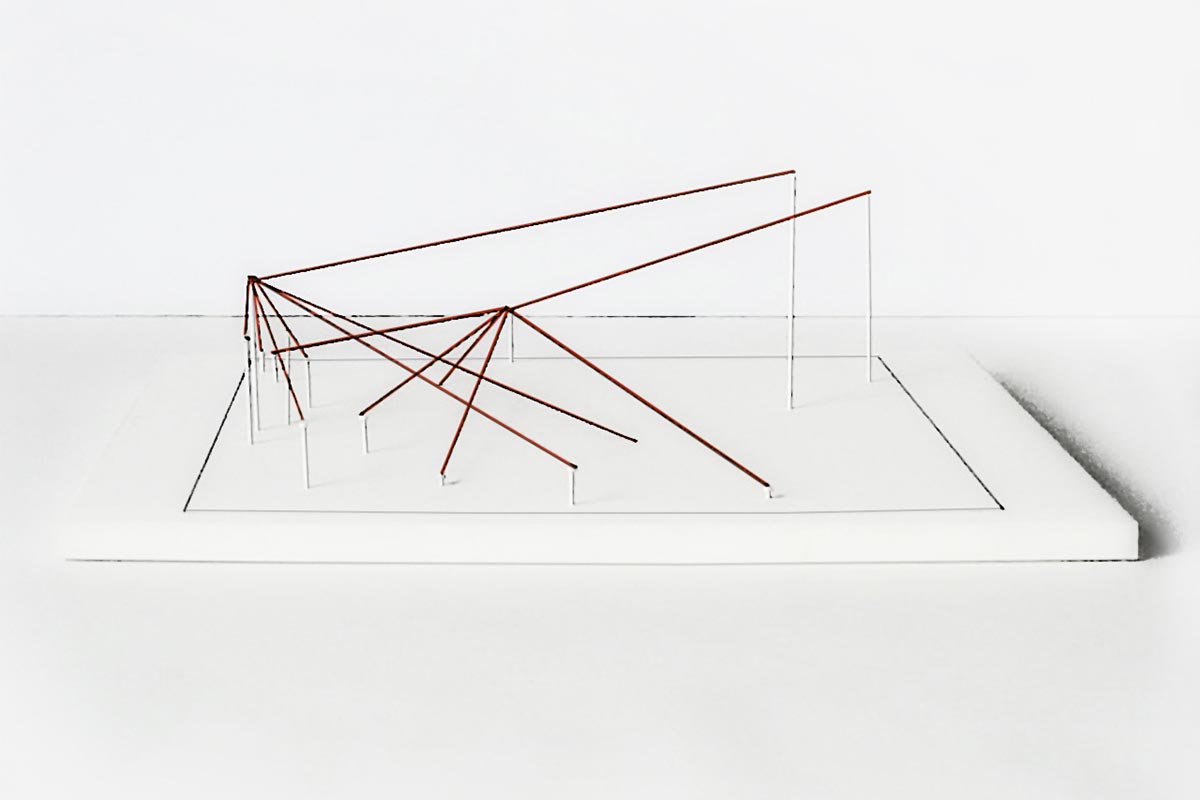

Concerning the important connection between body, action or movement, and space — point 2), above —, this was the overall sequence that I had in mind to generate architecture: A) body> B) action > C) space > D) architecture, that is: the human body, the primary subject of architecture, acts, behaves, and moves; these actions require space; space designed for the body, i.e., space for dwelling whether confined or partly confined, ultimately gives rise to architecture, satisfying our biological, social, and symbolic/aesthetic needs. I discovered a stable philosophical foundation in Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception, which enabled me to develop the first part of the conceptual sequence: body> action/movement> space.[20] In my initial spatial models, as showcased in Slideshow 4 below, I used cotton threads to represent ‘actions’, which referred to the movements and behaviors of people, such as moving from the living room to the bedroom or bathroom, the movement from a chair to the desk, etc. These threads, extended between pins, needles, or nails, symbolized the connections between different areas based on the architectural program; ‘space’ was represented by spaghetti or wooden sticks, which I created by selecting specific people’s movement configurations (that is connections or movements of users between different areas). The resulting spatial structure, composed of spaghetti, wooden sticks, or later, metallic wires, could also represent beams or pillars, adding a functional, structural layer. Finally, by incorporating closures and partitions to represent walls, roofs, and floors, I could generate a primordial form of architecture that defined specific areas, such as entrances, living rooms, bedrooms, etc.

Slideshow 4 (Images 28-32): Architectural studies (c. 1995); cotton threads were used to represent the movements or actions of people between different areas or spaces; once covered with planes, these trajectories defined specific spaces, such as halls, living rooms, and bedrooms, ultimately generating a basic form of architecture. In Image 28, one of the notes on the cardboard reads: ‘ESAUTORARE LA FORMA ATTRAVERSO IL MOVIMENTO (delle persone nello spazio)’ which translates to: ‘DEPRIVE FORM OF ITS POWER BY WAY OF MOVEMENT (the movement of people through space).’

Fundamentally, the decisive passages mentioned above — namely, 1) the individuation of space as the focus of architecture, 2) the individuation of bodily actions and movements as generators of space, 3) the identification of architectural and artistic examples focused on space and perception, 4) the identification of the specific perceptual information exchanged between bodies and the environment, and 5) the identification of topological space as the missing link between perceptual space and architectural space — after which I could devise archi-textures as a consistent mode of architectural production, were the result of my reflection and criticism on the relation between architecture and related disciplines, such as aesthetics, art, psychology, phenomenology, and the social sciences, all considered through the lenses of space and the human body. I have listed the five fundamental points following a certain logical and historical order, but, with the help of my notebooks from that period, I recall that I often processed acquired information in parallel, resulting in a certain overlap or intersection between different pieces of information related to each point, especially points 2 (the role of actions, movements, or behaviors in creating space) and 3 (contemporary aesthetic expressions with special spatial value). Envisioning and formalizing archi-textures was a laborious and time-demanding task for me, as it required combining diverse inputs from various disciplines into a cohesive, architecturally-oriented whole.

In Ersilia, to establish the relationships that sustain the city’s life, the inhabitants stretch strings from the corners of the houses, white or black or gray or black-and-white according to whether they mark a relationship of blood, of trade, authority, agency. When the strings become so numerous that you can no longer pass among them, the inhabitants leave: the houses are dismantled; only the strings and their supports remain.

From a mountainside, camping with their house-hold goods, Ersilia’s refugees look at the labyrinth of taut strings and poles that rise in the plain. That is the city of Ersilia still, and they are nothing.

They rebuild Ersilia elsewhere. They weave a similar pattern of strings which they would like to be more complex and at the same time more regular than the other. Then they abandon it and take themselves and their houses still farther away.

Thus, when travelling in the territory of Ersilia, you come upon the ruins of the abandoned cities, without the walls which do not last, without the bones of the dead which the wind rolls away: spider-webs of intricate relationships seeking a form.

ITALO CALVINO, Invisible Cities

Image 33: L’ARTE DI OCCUPARE LO SPAZIO / THE ART OF OCCUPYING SPACE. This image is taken from one of my early notebooks when I had already grasped the idea that space was the primary focus of architecture — the medium of human behaviours —, but I was still searching for a spatial language to translate this principle into practice (in the phrase above, on the left, I wrote: ‘for a design to be space-oriented, you need to think about people’s actions’; this generates the following sequence MAN> ACTION, i.e., MOVEMENTS AND BEHAVIOURS> SPACE> ARCHITECTURE). The image on the right, which represents a human figure reminiscent of Alberto Giacometti’s style, consumed by space, almost pulled by space, reveals my fascination with aesthetic expressions that evoke a strong sense of space or spatiality through plastic forms.

Slideshow 5 (Images 34-45): A selection of artworks (for details, see the section Image Credits, at the end of the article) which, during my years as a student of architecture, nurtured my interest in aesthetic representations of space and helped me develop my own spatial language—archi-textures.

From an architectural perspective, it is certainly true that, during my student years in the mid-’90s, I could draw inspiration from architects like Richard Maier, Bernard Tschumi, and Gunther Behnisch, who explored how people move through buildings, as in film sequences; Zaha Hadid’s early work, which examined the relationship between a building’s surroundings and the movement of people through it; Coop-Himmelblau and Peter Eisenmann, who deconstructed traditional architectural forms, such as platonic solids, and fueled my research against classical architecture and ‘pure stereometric forms’ (heritage of the International Style) that seemed to me deployed from above by the creative gesture of a skilled architect, rather than the procedural construction of space ‘built’ from below by the body of the inhabitants of such space. At that time, deconstructivism, or the destruction of form and its reconstruction from below through the action of the body in space, was an important principle of my architectural conception (ironically the deconstructive movement in architecture, regardless its promising beginnings, finished being as formal as the postmodern movement that it wanted to contrast, if not even more formal than it). Again, I could count on Steven Holl, who successfully translated phenomenological research into built architectures. On a more theoretical level, I could draw inspiration from Christian Norberg-Schulz, whose work connected architecture, phenomenology, and the value of space and place to Heidegger’s concept of dwelling, a fundamental issue in architecture.

Slideshow 6 (Images 46-52): A selection of architectures and architects who, during my years as a student, fueled my interest in space and perception on both practical and conceptual levels (for details, see the section Image Credits, at the end of the article).

Although, as we have seen, I had valuable architectural allies, my spatial research required me to combine diverse elements, including architecture, art, psychology, physiology, philosophy, social sciences, physics, and topology, into a more personal coherent whole. It wasn’t until I encountered the work of environmental psychology pioneer James Jerome Gibson that I could formally develop my concept of architecture as archi-texture, a mode of expression through which architecture, by way of space, could transcend its physical limits and boundaries and extend into the broader physical environment or context, much like the human body does through perception and movement. Ultimately, all of those inputs from different disciplines were translated into what, at that time, I believed was the univocal language of architecture: space.

2.2 The Perception of Space and the Topological Organization of Perceptual Data

Through Gibson’s work, particularly my architectural-oriented interpretation of his 1966 publication The Senses Considered as a Perceptual System, [21] I was finally able to to develop an ecological or environmental aesthetics for my models by visualizing the information that a perceiving body can actively obtain from the environment; I also realized that the body, through its senses, proprioception, and oriented movements, projects the self into the surrounding physical environment. I realized that the body and physical environment share an intrinsic unity, or withness, and by applying perception principles to space creation, I believed I could extend this unity between the subject and environment to the object, namely architecture. Eventually space, reified through vector lines indicating the movements and perception of bodies in a physical environment, served as the unifying agent between the body and its surroundings, which encompassed architecture as one of its many facets.

Images 53, 54: Extension of the body into the surrounding space through its movements and perceptions. If we remove the body, only vectors representing the information exchanged between the body and its physical environment remain. In this way, I was able to reify space as a vehicle of information for architecture, just as I had envisioned years earlier, when I had my epiphany about space. On the right, The Stick Dance, choreography and costume by Oskar Schlemmer, Bauhaus courses, c. 1927.

By investigating the mechanisms of perception, Gibson pointed out those elements that define the spatial and material properties of objects (i.e., the physical environment) in their relationship with the perceiving body. He considered the senses as perceptual systems that cooperate with each other, ‘ways of seeking and extracting information about the environment from the flowing array of ambient energy’.[22] What environmental information do humans pick up while moving and perceiving the physical world, and how could I translate that information into architectural models?

On the basis of Gibson’s work, The Senses Considered as a Perceptual System, what environmental information do humans pick up while moving and perceiving the physical world?

1) The orientation of the body relative to the ground (postural orientation) and the world around (oriented locomotion, e.g., orientation of one’s body relative to points of interests such as landmarks, or other meaningful things, e.g., trees, sun, source of rumours, etc.), which are detected by what Gibson called ‘the basic orienting system’; 2) mechanical disturbances that are continuous (such as waterfalls), intermittent, (such as wind or air frictions), or abrupt (such as the rolling, rubbing, colliding or breaking of solids); the vocals of animals, the speech and musical performances of humans, and machine sounds (the sounds from technological civilization), which are detected by ‘the auditory system’; 3) information detected by ‘the haptic system’ — the term “haptic”, from the Greek, meaning “able to lay hold of” — [23] the system literally in touch with the environment through skin receptors, tissues, muscles, tendons, and bones providing information about the body (kinesthesis and proprioception) and the physical environment, such as the exposure to the sun and winds (touch temperature and air temperature), differences like indoor/outdoor or above/below position, the texture of objects, the surface of the ground, and so on; 4) information detected by ‘the taste-smell system’, which recognizes particular natural odors (e.g., trees, flowers, sea, etc.) or artificial odors from technological civilization (e.g., smog, cars, industries, etc.); 5) the borders of things or objects (ambient array), the inclination of their faces or facets (differential facing), the chemical combination that determines their colors (reflectance), and the existence of attached and casted shadows (shadowing), which are detected by ‘the visual system’.

The slideshows below display a series of architecturally-oriented models I created based on Gibson’s indications about perceiving the environment. Initially, these models served as a guide to remind me of the various types of perceptual information exchanged between the body and the physical environment, which I needed to consider when starting a new project.

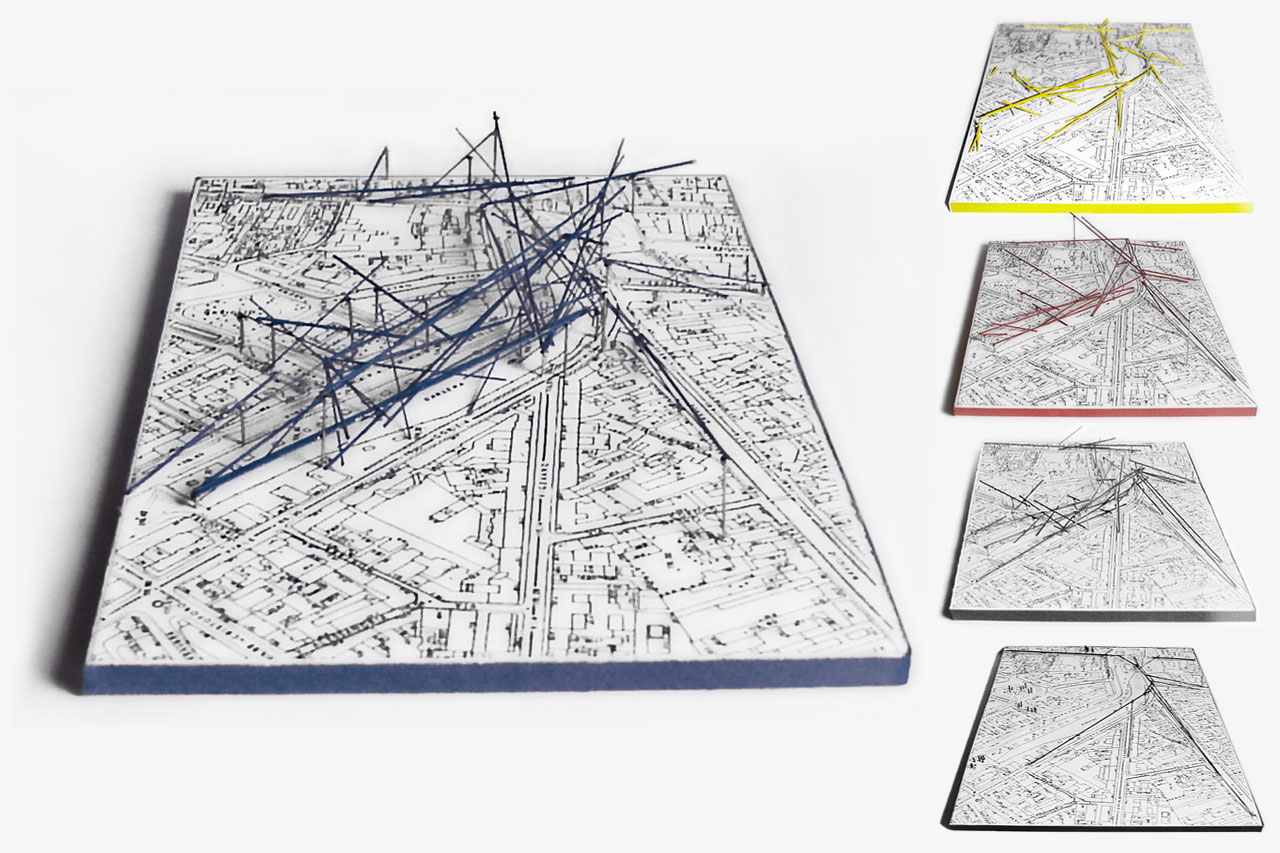

Slideshow 7 (Images 55-58): The Basic Orienting System. According to Gibson, the inclination of the ground and oriented locomotion, such as the presence of a landmark or a recognizable element in a landscape, are essential sources of perceptual information. In my models, this spatial information forms the ‘basic orienting field or space’, represented by the red lines (as shown in the final Image 58, where all material sources are removed, leaving only spatial information-pure space related to the basic orienting system).

Slideshow 8 (Images 59-61): The Auditory System. The auditory system detects various types of auditory information, including continuous, intermittent, or abrupt sounds (such as waterfalls, wind or air friction, the breaking of solids), the vocals of animals, human speech and musical performances, and machine sounds (the sounds from technological civilization). In the model, the yellow lines connecting the body to each source of auditory stimuli represent what I termed ‘auditory field or space‘, which includes the car on the left, the windmill above, the metallic solids at the center, and the group of people talking next to a river on the right, as examples of the auditory sources of stimuli listed by Gibson.

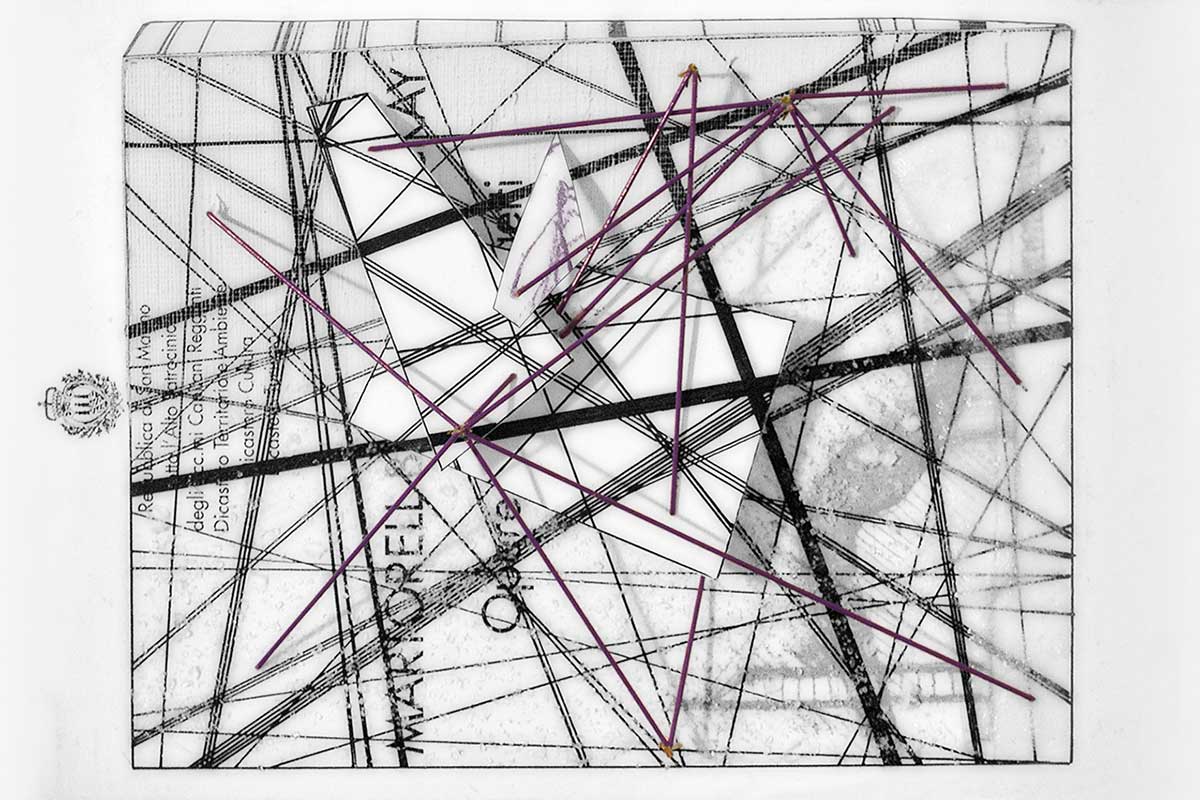

Slideshow 9 (Images 62-64): The Haptic System: the exposure to the sun and winds, differences such as indoor/outdoor location, above/below position, the texture of objects, and the texture of the ground determine basic perceptual information of bodies in touch with the world i.e., information that we commonly associate to the sense of touch. In the model above, the violet wires represent the ‘haptic field or space‘, which refers to the specific relationship between the body and various sources of stimuli, including rough terrain, level differences, unique textures of walls or roofs, and so on.

Slideshow 10 (Images 65-67): The Taste-Smell System. From an architectural perspective, the information gathered by the ‘the taste-smell system’ can inform decisions about which natural odors to allow, such as those from trees, flowers, or the sea, and which artificial odors to protect against, like smog or smoke from cars, industries, and so on.

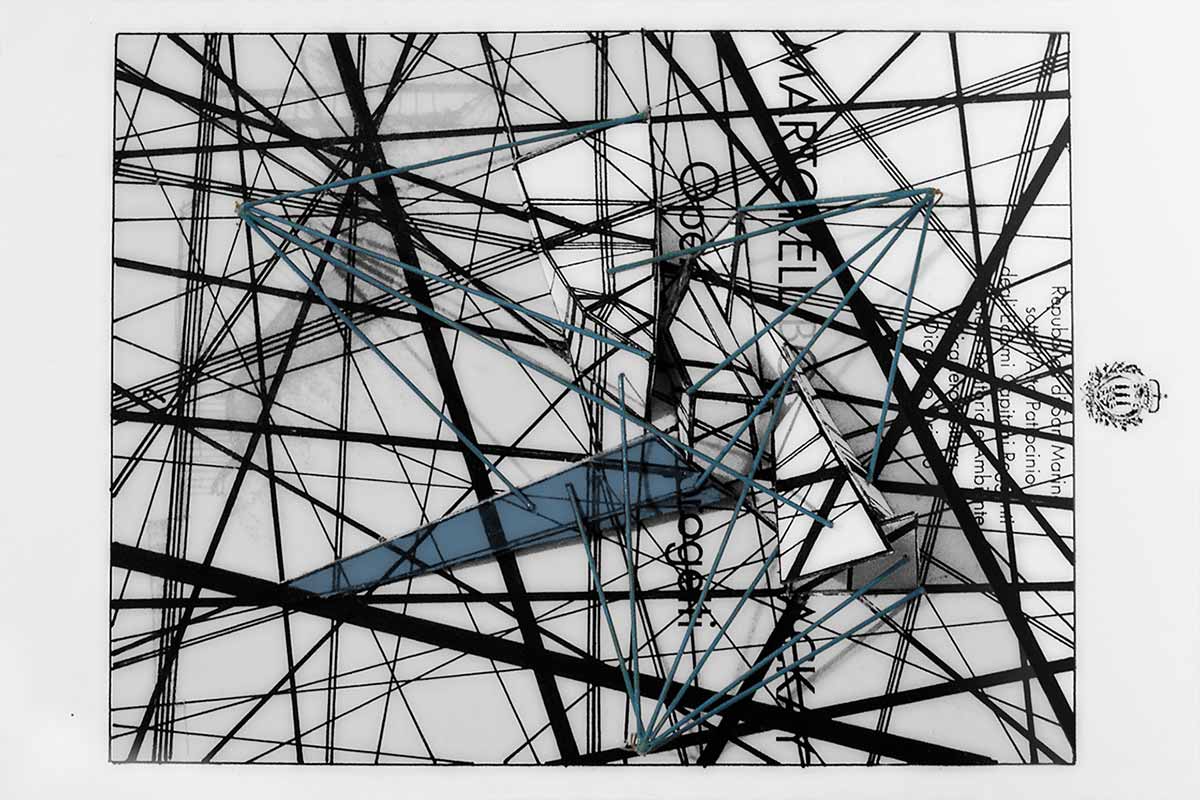

Slideshow 11 (Images 68-70): The Visual System. According to Gibson, the attractiveness of a visual space is determined by the borders of objects, whether imposing buildings or simple objects, their inclined faces or facets, colors, and cast shadows. The information in question represents the ‘visual field or space’, symbolized by the blue wires in my models above.

Of course, as I mentioned earlier, the movement, action, or behavior of people or bodies is a crucial factor in generating space. Although Gibson’s ‘haptic system’ encompasses kinesthesis and proprioception, which relate to bodily movement, I chose to dedicate a specific section to the movement and action of bodies, which I termed the ‘space (or field) of actions’, as seen in the slideshow below. In fact, this characterizing aspect of space and architecture played a crucial role in determining the final layout of a project’s spaces: it is the specific transition of a body from one place to another (locomotion) that generates successive sequences of perceptions (visual, haptic…).

Slideshow 12 (Images 71-73): The Space (or Field) of Actions. As also observed by Lefebvre, the movement of a body through space creates a text or texture that can provide insights into how space is used; tracking movements can even be used to create a new space that influences future behaviors by inviting to certain directions instead of others.

The combination of perceptual and motion inputs in a specific environment, represented by 3D wires and/or 2D lines, yielded the final spatial layout on which the new architectural project would be built or designed. Ultimately, I developed a way to transform the relationship between the body and its surroundings into a spatial structure that conveys the complexity of human existence, drawing on a phenomenological approach influenced by Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Bachelard.

Images 74-75: the human body as a generator of ‘space’ by means of perception and actions, or movements (i.e., behaviour).

Slideshow 13 (Images 76-80) Archi-textures: perceptual diagrams, activity diagrams, study models and final rendering of the Rainbow School, Prato, IT, by Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto, 2009. Project winner of the World Architecture Community Awards, 2009; project published in Architecture+Conception (Shanghai: IfengSpace), 2011; Eden for Boys & Girls (Hong Kong: Designerbooks), 2012. A videoclip on the construction of the archi-textures regarding this specific project can be seen on the You Tube page of RSaP.

Of course, I took some degrees of freedom in interpreting Gibson’s work, as my goal was to translate his perceptual inputs into a specific architectural language; as shown in Slideshows 7-12, I associated different physical environment elements (such as street volumes and surfaces, houses, trees, or physical bodies like the sun, moon, or river) with Gibson’s considerations. I linked these elements to the different perceptual systems of the body (visual, haptic, olfactory, auditory, and orienting systems) using metallic wires that connect the perceiving subject to the perceived object (landscape elements); additionally, I considered the actions or movements of people (as seen in Slideshow 4) as a key factor in generating architectural space, which I had previously identified as a major determinant. In this way, when I had to study the physical location for my architecture projects (site or place surveys), as a first step, I developed a three-dimensional web of relations between the site’s perceptual values, the required spaces for the building to function (such as a house, school, a church, a museum, etc.), and the possible actions and movements associated with the architectural programme. This web of information, which included connections between different areas, allowed me to visualize and reason about the space, providing a framework to generate and modify the emerging architecture based on various perceptual and functional inputs. For me, space became a means of connecting the body, with its senses and ability to move, to the physical environment, which I represented abstractly using lines, wires, and surfaces, encompassing both the indoor space of the building I was designing and the outdoor space beyond it, rather than a way to impose architectural forms from above as an external creation, where the architect acts as an all-powerful force — a deus ex machina.

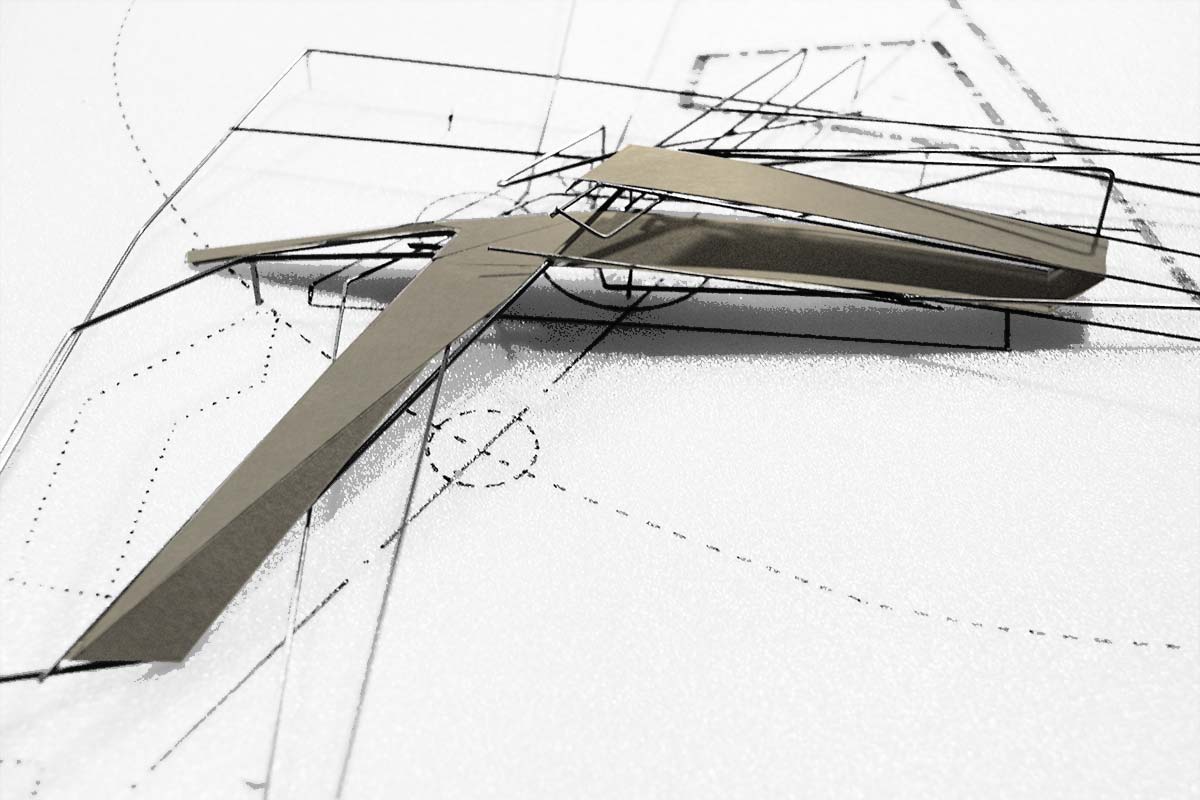

Images 81-82: From the web of spatial relations generated by the body perceiving and moving around a certain place I could derive the space of architecture by enhancing or dismissing certain inputs concerning perceptions and motions. At the beginning of the design process, the spatial structure made of wire is an analysis of the perceptual values of the physical environment (the perceptual analysis of the place or site of the project), associated with the actions, behaviours and movements that are possible in that environment on the basis of the architectural programme (diagrams of activity, i.e., areas/spaces necessary for a building to function). Images above: Archi-texture, study models for a library in Legnano, IT, Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto (2009).

Slideshow 14 (Images 83-85): Archi-texture, study model and final rendering for a library in Legnano, IT, Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto (2009).

As I mentioned above, in the opening section of paragraph 2.1, there was another crucial and final step (point 5, from the list) before I could envision a mature architectural language, which eventually evolved into fully-fledged examples of archi-textures: conceptualizing and organizing topological space as a prelude to developing and defining architectural space. The formalization of this final step was suggested by the seminal work of the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, although I was already drawn to topological studies in architecture and appreciated their practical use, especially for creating activity diagrams concerning people’s actions and connections between different areas/spaces.[24] In The Child’s Conception of Space Piaget explored the relationship between perception, oriented actions (movements), and the various phases through which humans develop a sense of space, which arises from the combination of these perceptions and movements.[25] Crucially for questions of space and architecture, I realized that our understanding of the surrounding world, acquired through sensory information and motor activity, is initially organized cognitively based on topological relations, such as proximity, separation, continuity, discontinuity, order, and enclosure; only later do these topological relations give rise to projective relations (geometrical relations) in our minds, ultimately forming the concept of space. Therefore, the creation of space in architecture should follow the same natural sequence. To put it differently, representational space, which is the type of geometrical space that architectural space is based on, is built on a more primary form of topological space, which, in turn, is fueled by the way the body seeks and extract information from the surrounding environment (Gibson). Based on these and other considerations derived from the study of topology,[26] I envisioned the following sequence to approach the various phases of architectural design: perceptual space > topological space > architectural space. Fundamentally, these three phases were the basic determinants of the mature language of archi-textures.

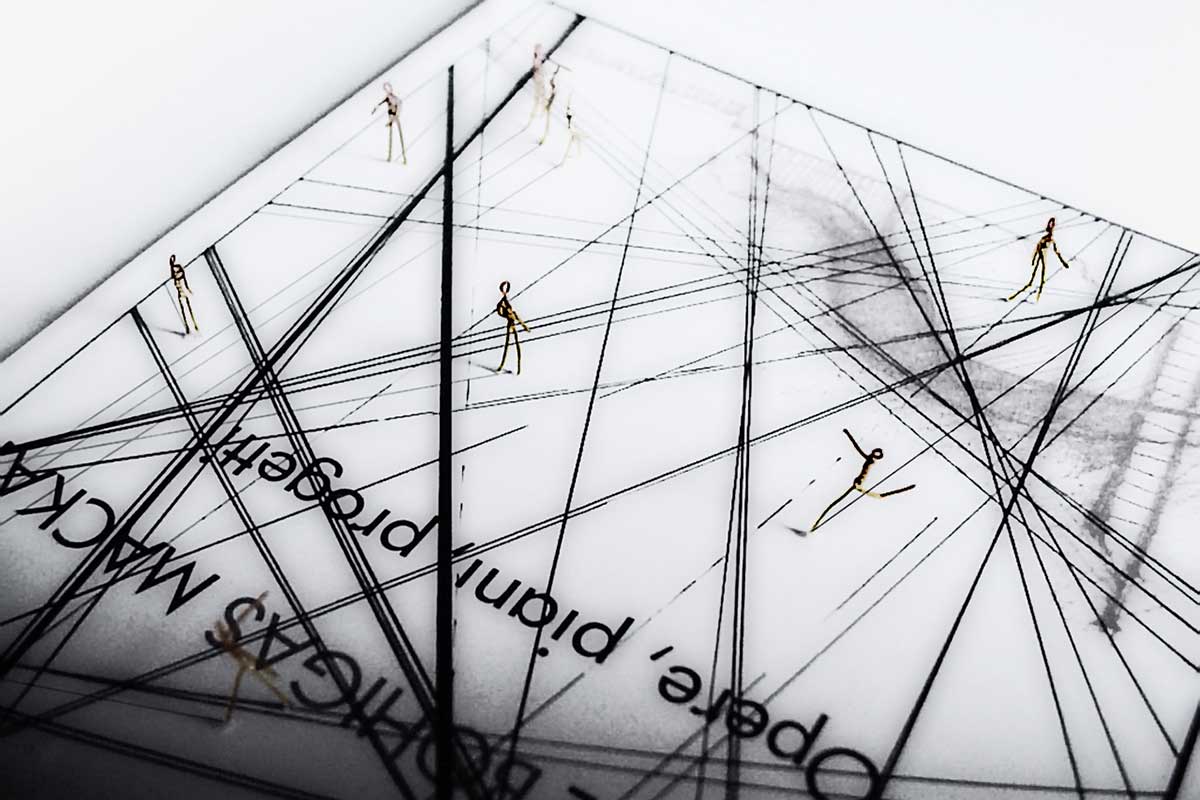

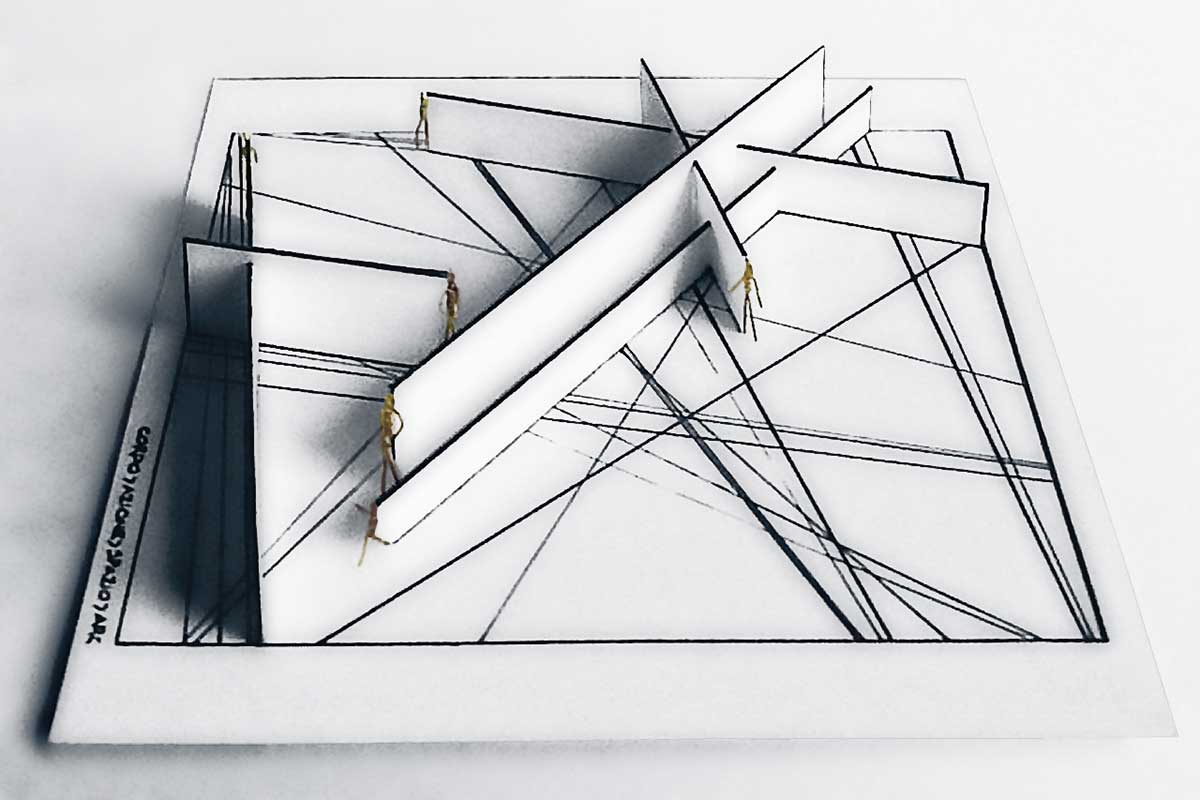

Slideshow 15 (Images 86-88): MAC Milano (Museum of Contemporary Art), in Milano, IT, Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto, (c. 1998). Within the domain of archi-textures, perceptual space, or the space of the senses (Image 86), topological space (Image 87), and architectural space constitute the generative spatial sequence of architecture.

By means of archi-textures, I was able to represent space as the fundamental sustaining medium for architecture, rather than just the medium for conveying perceptual and environmental information. Based on these representative models, which I saw as three/four-dimensional textures reminiscent of Lefebvre’s intuition, I could begin to reason about architecture by representing the fabric of space at the human scale. The step from archi-textures, which are abstract spatial models, to architecture, as concrete architectural models, is short, not just linguistically speaking. This is because archi-textures give rise to architectures by establishing topological boundaries that define various spaces, including open or closed, covered or exposed, indoor or outdoor, relations of continuity or discontinuity between different areas, etc. Within the realm of an ‘abstract’ 3D/4D model, by manipulating boundaries, thresholds, and divisions, which had an initial topological value — forerunners of architectural walls, roofs, or floors — I could enhance or dwindle the sense of belonging to a certain place, by firing certain perceptual sensations rather than others, according to my sensibility of architect, linking an imaginary or abstract space (the space of the project) to the real place; the result, archi-textures, represented a choral domain, in between the (abstract) space of the project and the concrete place that, in the origin, generated the different fields of perception (in the context of these models, by ‘firing a certain perceptual sensations’ or information, I meant the possibility to keep, multiply, or remove the metallic wires representing a certain information, such as the visual field on a beautiful landscape from a certain point of observation, or an auditory field generated by birds singing on a tree, or even the less appealing sounds of a motorway or of a busy road nearby the project area).

In brief, through archi-textures, I transformed my understanding of architecture from matter to space: from what we see (walls, floors, pillars, beams, ceilings, windows, roofs, etc.) to the invisible information conveyed through space, by means of those architectural elements which our bodies are engaged with through movements, behaviours, and all of the perceptual systems—architectural elements whose dispositions allow or deny our body to actively move, rest, enjoy, or refuse a certain physical environment. Archi-textures are fundamentally relational models where space, place, and time take precedence over matter. As I crossed disciplinary boundaries to study the meaning of spatiality, I discovered that my interpretation of spatial reality aligned with the principles of modern physics, from relativity to quantum mechanics. This physical interpretation, which views reality as relative and relational, gave me greater confidence in the robustness of my theoretical models, which, from then on, for me, acquired a universal validity.[27]

After completing my courses and receiving my degree, I came to realize that architecture is essentially an exchange of information between buildings and bodies through space – a tangible text conveyed through spatial relationships, rather than the creation of forms, which was my initial understanding of architecture when I enrolled in architecture school. The key to deciphering this text, or the information it conveys, lies in the human body, the inhabitant of space, and its ability to perform actions and movements within a building’s physical extension, as well as perceive that space with all senses, not just vision. Architecture is an affair of all the senses.

Slideshow 16 (Images 89-94): On Space and Man, archi-textures from my final thesis work at the School of Architecture, Politecnico di Milano, ‘Offanengo: La Giostra dello Sport’, A.A. 1997-1998, with architect Davide Benini. That conception of space was a consequence of my phenomenological readings. Later, when I extended my research on spatial concepts to other disciplines and philosophical doctrines, I reconsidered the ultimate truth of that conception (see the forthcoming paragraph 3).

3. From Space to the Physical Environment as Place of Processes

To rethink space as place – and not the reverse as in the early modern era – is the urgent task…

EDWARD S. CASEY, The Fate of Place

I am approaching the end of this article: I’ve completed my narration about the architectural language I called ‘archi-texture’, which had space as its main focus. I will now explain why I reevaluated my understanding of space as a concept, which I previously believed was the medium for exchanging information between humans and their physical environment – the essence of architecture and archi-textures alike.

Until now in this narrative, I have employed the same spatial vocabulary I used during my university years while researching the relationship between body, space, and architecture. This was a traditional spatial vocabulary, a common understanding of the term/concept of space, which I began to question over a decade after envisioning my first archi-textures. For me, the need to reassess the role of spatial concepts in architecture stemmed from a significant shift in interest: the reevaluation of architecture’s role in the second part of the first decade of the new millennium, prompted by the emergence of environmental concerns and the spread of ecological issues, now a primary topic in the field of architecture, beyond debate. The shift in architectural focus from the exclusive language of space (as I said in the Appendix of the article On the Ambiguous Language of Space, space has been the key-concept of architecture since the second part of the XIX century) to the more concrete notion of the physical environment has led the discipline to question spatial concepts, whether from a theoretical (as in my case) or practical perspective. Fundamentally, architects (not just architects…) are rethinking space as place, transferring some properties of place to space, even though they continue to use the term ‘space’ as a privileged linguistic reference. From the pages of this website (see also my paper From Space to Place: A Necessary Paradigm Shift in Architecture), I contend that this change should be guided by a more incisive reevaluation of the traditional meanings of spatial concepts – space and place – and a clearer definition of their semantic boundaries, rather than simply applying the characteristic aspects of one concept to the other. Why keep on calling ‘space’ what, in reality, is the place of physical, chemical, biological, ecological, sociocultural, and symbolic processes? I believe archi-textures already held that truth, situated between space (which I now recognize as a mere abstract entity) and place (the concrete stage of life and events), although I didn’t realize it immediately: like most of us, I used to call ‘space’ what I later discovered was truly a ‘place’, in many situations. In the following sections, I will explain how I recognized what I now consider an epistemological error (which has a technical name after Whitehead: fallacy of misplaced concreteness) – mistaking an abstract concept such as space, for the concrete reality, which has a place-based nature – and how this realization changed my understanding of spatial concepts and the nature of reality.

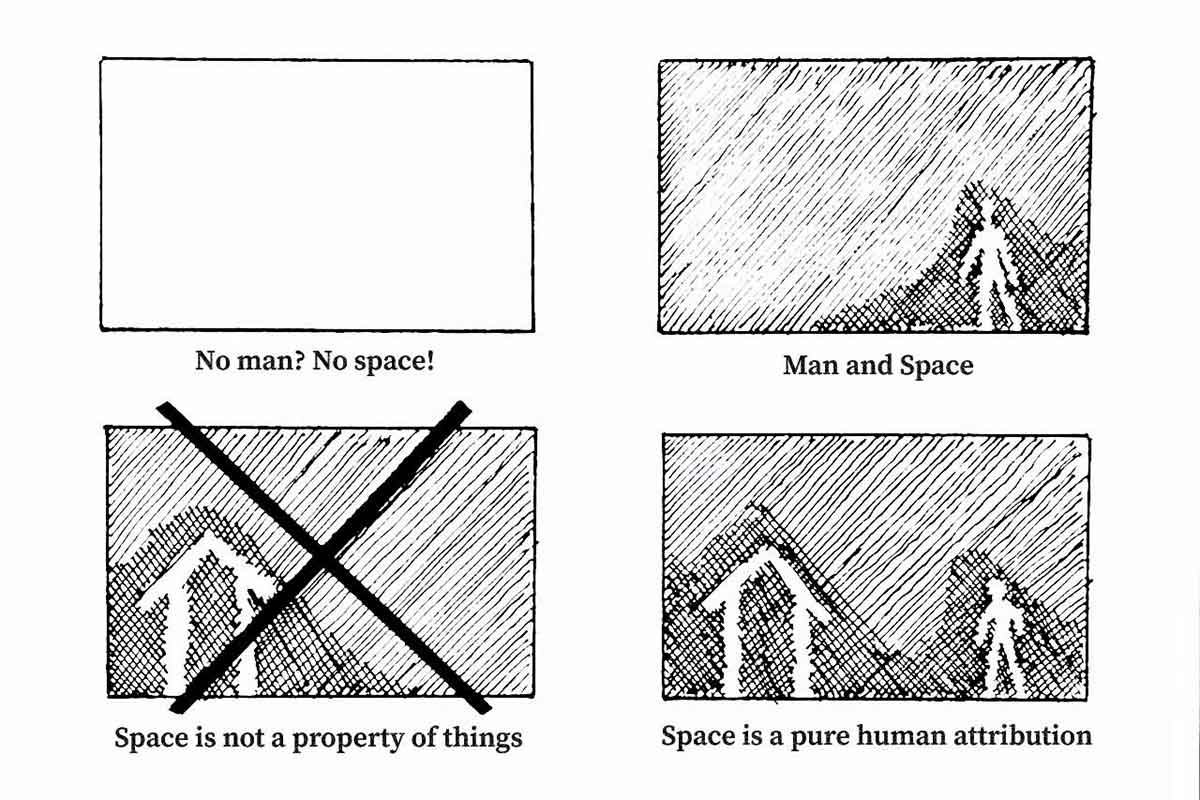

What is space? What is space, really? What’s curious is that everyone, especially architects, talks about space, but hardly anyone defines what space really is. As I showed in the articles Concepts of Place, Space, Matter, and the Nature of Physical Existence, Place, Space and the Philosophy of Nature, and Place, Space, Matter, and a New Conception of Nature, space is often taken as an unquestioned concept, which is, after all, an unclarified notion. Vocabulary definitions of space are mere abstract summaries, frozen abstractions that fail to capture the concept’s history and true epistemological sense of the concept. If we took the necessary time to study the complex philosophical and scientific histories behind spatial concepts, such as place, space, and the void, and their Greek and Latin variations, we would likely stop using with ease ambiguous expressions like ‘perception of space’ (e.g., see James J. Gibson on the Concept of Space), ‘physical space’, or ‘bodies moving through space’ when describing actual physical situations and experiences. Simply because space is not physical. It is a fallacy to believe otherwise; in contrast to common assumptions, there is no physical reality that corresponds to what we call ‘space’, apart from an abstract concept of geometrical origin. Any abstract concept, any idea actually, exists ‘in here’ (in our minds), so we should consider the correlation between what’s ‘out there’ and what’s ‘in here’, before assuming that space is ‘out there’. ‘Space’ is an abstract entity (a concept structured on the abstract notions of measure, distance, and/or extension – measure, distance or extension of what? Not certainly of ‘space’, which, history says, is derived from and not grounded in them) and since concrete physical bodies or entities exist and move in concrete places made of concrete things, such as the ground, the atmosphere, the sun, cars, persons, trees, rocks, and buildings, referring to these concrete entities as if they were ‘contained in space’ can be misleading and lead to errors. How can a concrete entity be contained in an abstract entity? This is the mother of all epistemological errors derived from a poor understanding of language. An ancient Chinese saying attributed to Confucius states: ‘If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If names be not correct, affairs cannot be carried on to success.’[28] I have dedicated the above-mentioned articles to exposing the modern, erroneous assumptions underlying the concept of space, which permeate common language and expressions and have shaped our traditional understanding of space. When discussing concrete situations, we should think and speak in terms of ‘place’, or ‘elemental things-place’, as Edward Casey suggested, rather than in terms of space. As Casey also observed ‘to be physical is to be in place’, not in space – I add.[29]

To be physical is to be in place.