01. Architecture, City, and Landscape as a Total Environment

I conclude this series of three articles focused on place, architecture and urban planning. While in The Place of Architecture The Architecture of Place – Part I: The Identity of Places I discussed the concept of place identity, proposing that the identity of a place should be understood in holistic and systemic terms to give an organic unity to the diverse perspectives and data through which places are typically analyzed—via the study of geology, climate, ecology, sociocultural histories, economy, architecture, and other different subjects—in The Place of Architecture The Architecture of Place – Part II: A Historical Survey, I examined how architects have addressed the notion of place as a distinct subject of inquiry, in both past epochs and more recent times. Following the spatial hypothesis I am discussing at RSaP—Rethinking Space and Place, if we accept that a comprehensive understanding of place requires engaging with all the fundamental dynamics—physicochemical, biological/ecological, sociocultural, and symbolic—that together form its unified structure, it becomes apparent that architects in the past have often addressed only selected aspects of place, typically its landscape or topographical qualities (physicochemical dynamics), the social implications of a new intervention (sociocultural dynamics) and, more recently, ecological implications (biological and ecological dynamics), while only rarely attempting to synthesize all the constitutive dynamics of place into a truly global and systemic perspective.

In this final article, I present a recent project I led in collaboration with a group of fellow architects, developed within a place-based framework grounded in a systemic understanding of place as the interplay of all physicochemical, biological, ecological, sociocultural, and symbolic dynamics—or, more concisely, the integration of natural and cultural dynamics. From an environmental perspective, I believe this encompassing, systemic, place-based approach to architecture and planning can complement existing environmental building protocols by offering a more holistic vision—one that embraces the full spectrum of dynamics shaping the environment in its architectural, urban, and natural dimensions.[1]

By understanding both places and architectures as products of the systemic interdependence of physicochemical, biological, sociocultural, and symbolic processes, we can more clearly identify pathways for the future of design practices. This means embracing a transdisciplinary approach—a non-hierarchical framework that moves beyond conventional multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary methods—toward a more unified and synthetic vision of reality.[2] More than any other approach, transdisciplinarity communicates the essential message of interdependence between natural and human systems. This principle provides the foundation for developing truly sustainable design strategies—ones that enable practitioners to move beyond the goals of simply reducing or avoiding harm to the environment, toward actively maximizing humanity’s positive impact, helping to regenerate the environment’s full potential.[3]

We should approach the analysis and design of architecture, cities, and the natural environment as a single systemic whole, where culture and nature coevolve in unity. Reality is inherently place-based: it is the place of interwoven processes that range from the physical and natural to the human and symbolic, regardless of the scale of observation. Planet Earth is a place; so too is the small country town of Ostiano—the territory of our design proposals—as are the streets and neighborhoods that compose it (Places Everywhere—Everything Is Place). The processual logic that underlies the functioning of places—their being and becoming through the concretion and continuous interplay of inorganic, organic, social, and symbolic processes—is fundamentally the same everywhere.

02. Place as System of Processes

Image 01: Reality is One, a whole place comprised of extremes acting as complementary and mutually dependent aspects or forces.

Place is the encompassing structure that allows the many different parts of reality to stay together and related, binding them into a single, coherent system—a whole. I call this whole place. Since place emerges from the interplay of diverse elements, we are prompted to ask: What are its constituent parts? Which fundamental dynamics shape its identity and character?

We already advanced our working hypothesis: at the most basic level, all aspects of reality can be understood as arising from four primary orders of processes—inorganic, organic, social, and symbolic.[4] When these processes take form—becoming actualized in ways that are perceptible or intelligible—they appear as recognizable patterns, which we typically interpret as things, life, societies, and symbols (see On the Structure of Reality). These structured patterns can themselves be conceived as systems, or places: the place of processes that may or may not manifest as tangible or intelligible forms.

The term system comes from the Greek sýn- (ancient Greek sun-), meaning “with,” “together,” or “in company with,”[5] and hístēmi, meaning “to stand,” “to set up,” or “to make stand.”[6] As Ludwig von Bertalanffy, the Austrian biologist and founder of General Systems Theory (GST), observed, “a system can be defined as a complex of interacting elements [where] the whole is more than the sum of parts.”[7]

In this sense, we can understand a system much like an organism: its parts are not autonomous entities that can be studied, observed, or understood in isolation from the larger context. Likewise, a cultural system—whether a city or an architecture—cannot be separated from the natural, biological, and social systems of processes from which it arises. These systems form an organic concrescence: a “growing together” of antecedent elements into a new unity. This is a mode of “standing together” in which the parts behave as a whole, shaped by the overarching structure that contains them.[8] Place is this unitary structure or whole—a system of processes.

Image 02/03 (shift the cursor to see the images): Place as System of Processes. Place, as a complex system of interacting processes, must be understood as an organism where the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Out of the relationships between parts, a new organic unity emerges: this unity can be thought of as a system – ‘the place of processes’.

The four general categories of processes—inorganic, organic, social, and symbolic (see Image 02)—which together shape places as indivisible wholes, can be further refined (see Images 03 and 05). For example, ecological processes, which couple inorganic and organic dynamics (abiotic and biotic components), emerge as a concretion stage from underlying physicochemical and biological processes. This follows well-known principles of systems behavior.

According to basic evolutionary principles, systems of processes develop as a concrescence from “lower” to “higher” levels of existence—that is, from the simple to the complex. Thus, basic physical processes (governing the dynamics of fundamental components of reality such as quarks, atoms, and electromagnetic fields) give rise, over time, to more complex patterns, such as chemical, biological, ecological, sociocultural, and, eventually, symbolic (governing immaterial human dynamics such as the establishment of values, ethics, religious beliefs, artistic aspirations, etc.). Every process can find its place within the schematic wheel of processes shown in Image 05.

It is almost a truism to say that the identity of a place emerges from the full range of processes present there, while its character is shaped by the intensity with which these processes unfold. What is crucial to emphasize, however, is that identity and character are comprehensive, indivisible qualities that cannot be interpreted in reductionist terms. Whenever we intervene in a place, every dynamic of that place—physicochemical, biological, social, and symbolic—is potentially affected, and all participate in shaping its identity and character. These dynamics cannot be considered in isolation: they influence each other, they require each other, and lead on to each other.[9]

The web of lines depicted in Image 04 illustrates the intricate interconnections between the various dynamics and processes of a place. It is from these interwoven and cumulative dynamics that systems emerge as wholes—the place of processes. This whole is an encompassing, incremental, and concrescent structure, arising from the relationships among its parts.

Interpreting place in systemic and processual terms often resists confinement to a fixed area (the site of the project) or a short time frame. The boundaries of processes are difficult to define both spatially and temporally; they frequently extend across geographic or human-made limits and temporal intervals (see The Identity of a Place: Place-Based Interventions Between Land and Society).

Images 04/05 (shift the cursor to see the images): Identity and Character of Place. Identity and character of places are emergent qualities deriving from the specific nature and intensity of processes unfolding in a certain region. The type of processes represented in the diagrams are just a basic representative categorization of the multitude of processes that actually exist in any place.[10]

Image 06: Identity and Character of Place. Even if we can set specific categories of processes, a place is an undivided whole, an incremental and concrescent unit where processes influence each other, require each other, and lead on to each other, in the range from inorganic to symbolic; higher orders of processes include processes of lower order.

Every place possesses its own peculiar identity and it is the proper task of man to comprehend that identity and take care of it.

CHRISTIAN NORBERG-SCHULZ, Architecture: Presence, Language and Place

03. A Case Study: Adaptive Reuse of Three Compounds in the Country Town of Ostiano, Northern Italy.

03.1. From Sustainable to Regenerative Design

We have set a higher standard of environmental awareness for the project of rehabilitation of three districts in the small country town of Ostiano: the shift from a sustainable approach to a regenerative one. We believe that the role of design is not merely to be “sustainable” in the conventional sense—minimizing or mitigating the negative impact of human activity on the natural environment in response to climate change and ecosystem degradation. The true aim should be to foster a mutually beneficial integration of human and natural systems, enabling them to co-evolve in ways that reverse environmental damage and actively improve current conditions.

This shift means that human processes must harmonize with natural processes so that both can continue indefinitely, supporting and reinforcing each other for the benefit of future generations and species. Such an approach inherently requires a holistic, systemic worldview—one that expands the boundaries of sustainable thinking to embrace and promote the regenerative potential of each environment, understood as the integrated whole of its natural, social, economic, and cultural dynamics.[11]

Caring for the environment as a whole, therefore, is not simply about preserving the status quo or reducing CO₂ emissions to near-zero levels—metrics commonly set by sustainable development. The real challenge is to create life-enhancing conditions that move us toward a climate-positive, regenerative balance.[12] By “life-enhancing conditions,” we mean not only the physical environment but also the economic and socio-cultural environment—where cultural refers to the ways of living, styles, education, narratives, values, and beliefs that give each place its unique shape and character.

Within this systemic perspective—where all aspects of reality, from natural to cultural, contribute to defining the identity and character of a place—place becomes the central reference point and organizing concept for setting goals in both sustainability and regenerative development. Consequently, the study of place must be regarded as a fundamental operational tool in initiating any project, alongside standard considerations such as program and technical requirements. Through architecture, the character of a place can be revealed.

03.2. Ostiano: The Program

The purpose of this project is the environmental requalification and adaptive reuse of a group of buildings located across three districts in Ostiano, a small town in Northern Italy. Once restored, these buildings will accommodate a new industrial company in the solar energy sector, specializing in energy storage technologies and solutions, and producing batteries, power conversion systems, and energy control and monitoring systems.

Image 07: Localization of the three districts, in the country town of Ostiano, IT. Requirements of the brief: 1] A production plant with offices and a short-term warehouse (Località Cossone); 2] Headquarters and R&D divisions (ex-Consorzio Agrario); 3] Long-term warehouses (Belvedere).

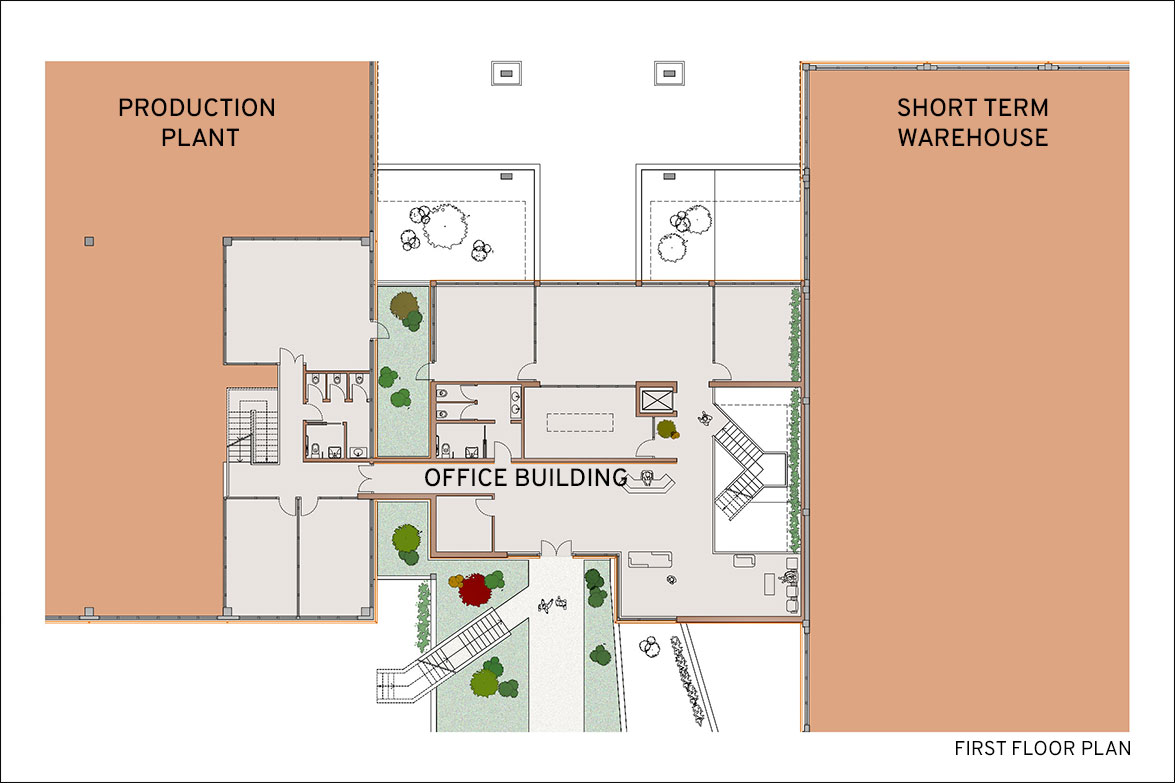

Località Cossone – an industrial area near the countryside – will see the restoration and redevelopment of two existing prefabricated warehouses to house the new production plant, along with the restoration of one building for the temporary storage of assembled items. Between the two warehouses, a new office building will be constructed on already on an already built piece of land.

The second district, located in a residential area near the town center, involves the restoration and redevelopment of the former Consorzio Agrario—currently abandoned and not under heritage protection, despite its symbolic, anthropological value.[13] This site will be transformed into the company’s administrative and representative headquarters, housing research and development laboratories, educational and exhibition spaces, and public areas for dining and recreation.

Finally, the third district, known as Belvedere and located within the town’s historic core, will be dedicated to securing existing warehouses for the storage and long-term deposit of items produced by the plant. Here, the intervention is limited to removing asbestos from the old roofs and reconstructing them with traditional clay tiles typical of the historic center.

Video 01: Situation before the project: Località Cossone, ex-Consorzio Agrario, and Belvedere.

Taken together, this is a comprehensive program that we conceived as a unified and integrated project—not only in functional and operational terms for the new company but also in its relationship with the natural environment and the town itself, Ostiano, which is the physical expression of place, history, and community; it will directly benefit from the project through new employment opportunities and strengthened social inclusion.

03.3. Ostiano: The Place of Physicochemical, Biological, Ecological, Sociocultural, and Symbolic Processes

Images 08-12: Ostiano is a small country town in the middle of the Po Valley of Northern Italy. Unique environmental and sociocultural processes have shaped the identity and character of this place.

Images 13-20: The approach to place begins with surveys and the systematic collection of data, which are then processed and organized to reveal the different layers that structure the identity and character of a land or territory. Since places have evolutionary structures, it is logical to begin with an analysis of PHYSICOCHEMICAL PROCESSES—such as soil formation and climate—in order to understand the fundamental forces that have shaped the territory. Geographical, geological, geomorphological, hydrological, pedological, and seismic maps and sections, together with climate data (including sun path diagrams, solar energy values, average rainfall, wind speed and direction, air temperature, and humidity), provide the essential foundation for understanding the physicochemical layers of a place.

Images 21-25: Following the logic of evolutionary development, once the physical formation processes of a place have been examined, the next step is to study its existing flora and fauna—the domain of BIOLOGICAL PROCESSES—and their interactions with the physical environment—the domain of ECOLOGICAL PROCESSES. Key sources of information include maps showing the distribution and localization of vegetation types and wildlife species, complemented by regional, provincial, and municipal ecological network maps. Together, these provide a comprehensive understanding of the living systems that interact with, and are shaped by, the place’s physicochemical foundations.

Images 26-31: The analytical inquiry into the identity of a place then turns to the historical presence and activities of humans within the territory. Anthropological records, economic data, historical narratives, and urban plans are essential sources for tracing the sequence of SOCIOCULTURAL and SYMBOLIC PROCESSES that have unfolded in a place over time. In addition, specific mapping of how human bodies relate to the project site and context—through perception—is crucial for identifying distinctive environmental features that can be integrated into design proposals. Such maps represent the place of human physiological and psychological processes (potential human adaptation to the new setting, including the project: see the article Archi-textures for further discussion on how mechanisms of environmental perception can inform architectural design).

The systemic conception of place we advocate reaches far beyond the purely physical–geographical or social dimensions that architects have traditionally addressed. This expanded understanding encompasses the physical, biological, ecological, social, cultural, historical, and symbolic aspects of place as an indivisible whole.

Like concentric ripples spreading across a pond, this broader dimension of place extends outward, linking with adjacent places to form a shared network—one that binds together all its components: living beings, the earth, and the sky—into a single, interconnected structure. We, as human beings, are integral to this network, for we are made of it. We are all places. This is the new contract between humanity and nature in the epoch of the Anthropocene.

03.4. Design Indications from the Systemic Analysis of Place: Implementation of Natural and Sociocultural Dynamics

Image 32: The analysis of place provided several suggestions that are responsive to the dynamics already taking shape in the territory. It offers opportunities to build upon these existing dynamics while also creating new ones for the built environment. Such dynamics can regenerate the potential of the place, enhancing its identity and character.

Image 33: The distant line of the horizon, often marked by rows of beech trees, is a characteristic of the landscape to preserve and enhance in the Po Valley, as also reported by the regional and municipal regulations (Documenti di Piano, Piano Territoriale Regionale).

Situated alongside the naturalistic valley of the Oglio Sud Park, Ostiano stands on a morphological terrace overlooking the left bank of the Oglio River Valley, at its confluence with the Mella River, in the heart of the Po Valley. This territory has long been shaped by two powerful hydrogeological forces—the Oglio and Mella rivers—which have defined its agricultural vocation since prehistoric times. Archaeological evidence confirms human settlement here as early as the Neolithic period, with findings scattered across the landscape.

The project is guided by shared environmental, social, cultural, and symbolic principles. On one hand, the presence of water and greenery within the design evokes the naturalistic and agricultural character of the territory. On the other, the use of brick as the primary construction material connects the architecture to the clay-rich soil of the land and to a deep-rooted heritage of craftsmanship, technological expertise, and aesthetic traditions that have evolved over centuries: from an anthropological perspective, archaeological discoveries suggest that early human groups exploited the clay soil as a natural resource—initially to produce ceramic artifacts, and later, in the Roman period, possibly establishing Ostiano as a production center or trading post for ceramic goods. The combination of clay-rich earth, abundant water, local silica, and plentiful timber from surrounding woods and fields provided all the essential resources for clay production and firing. This technological and economic heritage endures today, as evidenced by the continued operation of a brick factory in the area. The frequent appearance of the term fornace (“furnace”) in local place names further attests to the historical importance of brick kilns. The use of exposed brickwork remains a distinctive architectural feature of Ostiano and can be seen in some of its most important and ancient monuments, including the Gonzaga Castle and the pre-Romanesque Church of Torricella (Images 11, 12).

Historical sources: M. Brignani e V. Ferrari: Toponomastica di Ostiano; Gruppo Hobbistico Ostianese: Saluti da Ostiano; G. Merlo: Ostiano: Tra Arte e Storia; G. Merlo: I Tesori di Ostiano; F. Morandi: Momenti di Storia; G. Regonini: Ostiano: Le Origini ed Alcune Note Storiche.

03.5. The Projects

In keeping with the project’s overarching regenerative vision, the design aims for zero land consumption while meeting the functional requirements of the new company’s diverse activities. At Località Cossone, the new offices are positioned at the terminus of an existing access ramp, adjacent to pre-existing underground storage tanks made of reinforced concrete. These tanks will be repurposed for rainwater collection, upon which the new offices will be built.

Images 34/35: Confrontation of new and old buildings in Località Cossone. On the left and right, respectively, stand the restored buildings for the production plant and the warehouse. To improve energy efficiency, the existing facades will be upgraded with a ventilated terracotta wall system. The new office building, positioned between the two restored structures, will feature a massive construction with exposed brickwork, also designed for optimal thermal performance. The intrinsic natural value of the surrounding territory is preserved and enhanced through a biophilic design approach, shaping both the outdoor areas and the interior spaces to foster a closer connection between occupants and the natural environment for a better psychological adaptation to the new working environment (Design Team: Calvi Rollino, Cereda, Panarese Architetti).

Images 36 (above), 37 (below): View of the South Façade and interior view of the new office building, Località Cossone.

Images 38/39 (shift the cursor to see the images): Località Cossone, ground floor plan and first floor plan of the new office building.

Image 40: Aerial view of the project for the compound in Località Cossone.

Concerning the ex-Consorzio Agrario, the restoration and adaptive reuse of the existing buildings serve a dual purpose. First, they embody the principles of the circular economy—reducing, reusing, and recycling resources—which in turn lowers CO₂ emissions compared to new construction. Second, they safeguard the historical memory of a location that once played an important social and economic role, particularly during the period when agriculture was a central training sector in Italy. Within this framework, the project operates at the intersection of social, cultural, and symbolic values. It preserves the socio-economic legacy of agricultural consortia, or granaries, while also recovering the memory of ancient crafts and technologies tied to the region’s clay-rich soil through ceramics and brickwork. This is achieved by exposing the underlying brick layers of the existing facades and walls of the main body of the ex-Consorzio (see the confrontation of Images 41-42, and below) and reusing them as the restored finishes for both facades and interiors. The intrinsic monumentality of the ex-Consorzio Agrario—with its barrel vaults and lateral spans—finds new life as research laboratories and a conference hall, also for public use. The transformation lends the building the aura of a modern Basilica, marking a functional shift from agriculture to culture as a new form of religion. This architectural reimagining draws from the Latin root of religion (religio, from re-ligare, “to bind again”), symbolizing a renewed covenant between humans and the environment—one based on an integrative, dynamic, and regenerative understanding of place and its care. The use—and reuse—of clay and brick serves as both a functional and symbolic cornerstone of this new contract between the natural environment and human activity: clay, a local resource shaped by nature over geological time, is transformed through human craftsmanship into enduring architecture.

Images 41/42: Ex-Consorzio Agrario, confrontation of new and old buildings. The recovery of the underlying brick layers in the existing facades, the use of brick for paving and seating, the incorporation of water features, the design of an elevated walkway, and the planting of tree rows are all elements that integrate with and reinforce the existing environmental, sociocultural, and symbolic dynamics of the place (Design Team: Calvi Rollino, Cereda, Panarese Architetti).

Images 43/44: The solid appearance of the ex-Consorzio Agrario, with its exposed brickwork and barrel-vaulted roof—to be reinforced to support the installation and maintenance of photovoltaic modules—now evokes the image of a modern Basilica. The green terraces at different levels, beyond aiding in runoff water management and providing pockets of biodiversity, echo the natural morphological terraces shaped over ages by the Oglio and Mella rivers, a defining topographic feature of this region.

Image 45: The new elevated walkway, while linking the working areas, frames a distinctive view of the horizon—the meeting point of earth and sky, behind which we find the fundamental physicochemical forces that have shaped these lands. It also serves as a symbolic evocation of the ancient act of crossing a river: in antiquity, Ostiano was believed to be the key location in the area where the Oglio River could be forded, a strategic reason for the Romans to establish their encampments here. Flanked by two rows of trees—emblematic features of the nearby agricultural landscape—the walkway becomes both a literal and metaphorical bridge, reconnecting people to nature. Through such details, the design weaves together the natural and sociocultural place-based dynamics that define Ostiano’s identity.

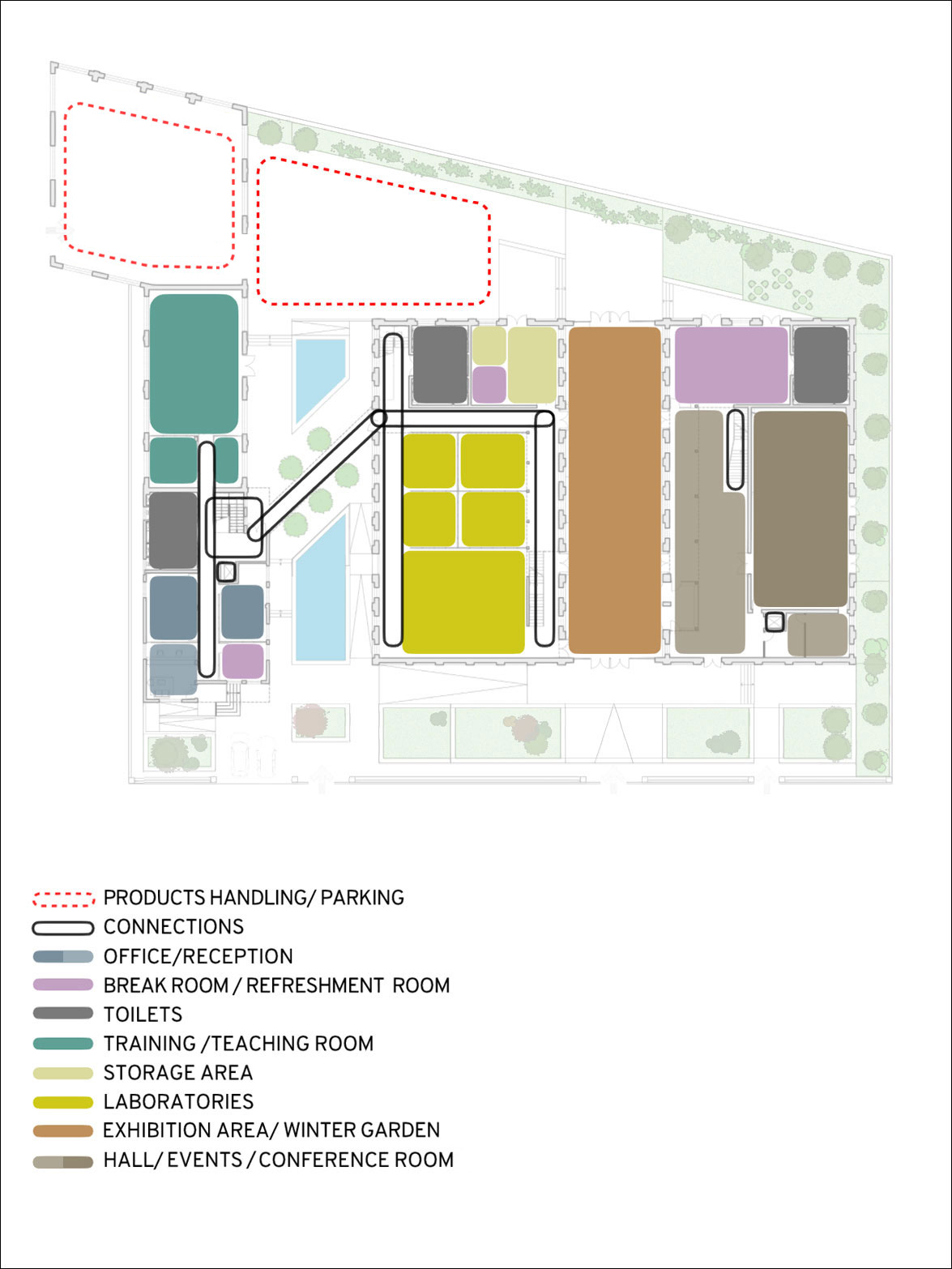

Images 46/47 (shift the cursor to see the images): Ex-Consorzio Agrario, functional diagram / ground floor plan

Continuing with specific design choices aimed at fostering social, economic, and environmental regeneration, we ensured these strategies would be immediately perceptible, not merely rhetorical. Water—shaped by the enduring forces of the Oglio and Mella rivers—becomes a defining element of the projects. Runoff is managed through permeable surfaces: terracotta paving at the ex-Consorzio Agrario and stabilized gravel in Località Cossone. Rainwater is collected and stored in aesthetically characterizing reservoirs, expressed as linear pools and fountains (at the ex-Consorzio Agrario) or as bio-pools (in Località Cossone). These measures both reduce environmental stress during heavy rainfall and enhance the naturalistic character of the built environment, reinforcing its biodiversity and strengthening its genius loci.

The design also celebrates the natural morphology and ecological richness that have long supported diverse habitats and avifaunal species. At the ex-Consorzio Agrario, green terraces recall the layered topography of the territory, while in Località Cossone, generous green areas extend the biophilic approach, mirroring existing natural and perceptual dynamics. The result is a network of healthy, visually engaging outdoor environments that, in turn, support well-being for indoor staying. In this regard, the interiors of the new offices in Località Cossone (Image 37, above) are conceived to maintain visual continuity with the surrounding greenery. Green interior walls, abundant plant life, and ample natural light—including zenithal illumination, a key atmospheric feature of place—enrich the indoor experience. Combined with thermohygrometric control strategies such as massive masonry walls, brise-soleil shading, green roofs, and natural ventilation, these measures create optimal conditions for environmental quality and human comfort in daily work life.

Beyond the restoration and reuse of existing buildings, the project extends its regenerative, circular economy approach—reduce, reuse, recycle—into other aspects of construction. In Località Cossone, we preserved and repurposed pre-existing wooden pergolas, relocating one to better serve the new spatial organization of work activities. Debris from two structures slated for demolition will not be removed but reused on site, cutting operational costs and reducing CO₂ emissions. This material will form the substructure for landscaped green slopes planted with flowers and shrubs, linking the elevated walkway of the existing ramp to the ground level (Images 34 and 36, above). The ramp itself, along with its reinforced concrete retaining walls, has been preserved and integrated, turning a problematic pre-existence into a defining element of the complex’s external circulation. From this elevated vantage point, one can take in the characteristically horizontal horizon line of the Po Valley to the east and, to the south, the urban landscape of Ostiano—two views that anchor the site in both its natural and cultural contexts.

Image 48: Horizontal silhouette of the urban and natural landscapes.

In terms of energy efficiency, brickwork was selected as the primary construction material for both the redevelopment of the existing warehouses in Località Cossone—where ventilated terracotta facades will be added as an external layer to improve thermal performances—and for the ex-Consorzio Agrario. It is also the defining element of the new office building in Località Cossone, designed as a massive structure with exposed brick cladding and terracotta sun-shading on the south-facing façade. This decision extends beyond the geographical, cultural, historical, logistical, and aesthetic reasons already mentioned: from an economic and environmental perspective, bricks—abundant, locally sourced, durable, and stable in performance—offer a cost-effective solution that is also recyclable and reusable at the end of a building’s life cycle. These qualities allow the project to meet multiple regulatory requirements set by the recent Italian Criteri Ambientali Minimi (CAM) for sustainable construction.

In addition to material performance, the energy strategy includes the installation of photovoltaic modules on all redeveloped buildings. In Località Cossone, a dedicated photovoltaic park will further supply the plant’s energy needs while generating surplus electricity, providing both environmental benefits and economic returns.

Finally, to ensure that the new interventions are meaningfully integrated into the social fabric, a portion of the ex-Consorzio Agrario complex has been designated for public use (see Images 46/47 above – the pavilion on the right). This area hosts functions that encourage gathering and social interaction, including indoor and outdoor dining spaces, refreshment rooms, and a conference hall that can also serve as a cinema and theatre activities.

To enable multiple, parallel uses without disrupting the Company’s operational activities, the overall spatial layout and interior spaces are arranged in a gradual transition from private to public. The left-hand pavilion accommodates offices, educational spaces, and laboratories; the right-hand pavilion, positioned closer to the pedestrian route leading to the Castle and the town centre, contains the public facilities such as the bar/refreshment room and the events/conference space. Between them lies a covered, openly accessible exhibition area designed as a winter garden; this central space acts as a buffer zone, harmonizing the flow between private and public uses while adding an inviting, biophilic character to the complex.

Notes

[1] Known protocols for sustainable architecture were born out of a reductionist and mechanistic mindset; this approach is too narrow and limiting to understand the complex relationship between architecture and the environment. Despite that, such protocols certainly contributed and are still contributing to creating an interest in the adoption of green building standards. See Chrisna du Plessis, ‘Towards a Regenerative Paradigm for the Built Environment’ In Building Research & Information, 40(1), (2012): 13.

[2] On the difference between multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches, see note [16] in the article On the Modernity of Patrick Geddes (1854-1932)

[3] As transdisciplinary thinkers Ruano and Pasquier maintained: ‘There is an urgent need to develop a complex, intercultural, transdisciplinary way of thinking, in order to more fully account for transnational damages of an intersystemic nature.’ Ruano, J.C., Pasquier, F. ‘Transdisciplinary’, in Handbook of the Anthropocene: Humans between Heritage and Future, edited by Wallenhorst, N. and Wulf, C. (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2023).

[4] Whitehead, in Nature and Life, talked about ‘six types of occurrences in Nature’ (‘human existence’, ‘animal life’, ‘vegetable life’, ‘single cells’, ‘inorganic aggregates’, ‘happenings on an infinitesimal scale’) – see The Place of Processes: Nature and Life. General System Theory categorized different levels of reality, which, in one way or another, include all of the categories mentioned by Whitehead (von Bertalanffy and Boulding see From Space to Place). Reminding Occam’s razor, I’ve found that the categorization offered by philosopher and novelist Robert Pirsig on the basis of systems theory is the most efficient and direct (see On the Structure of Reality), reducing the ingredients of reality to just four basic topics or systems which include ‘everything’: Inorganic, Biological, Social and Intellectual systems. Based on a processual (Whitehead) and systemic (GST) approach to reality, I have considered those four basic topics both in terms of processes and systems (physicochemical, biological, social and symbolic processes/systems, in a range from concreteness, which regards every being or entity, to abstraction, which only regards human processes or systems). If processes become concrete, they concretize into actual systems, otherwise, they remain in their potential state, waiting for realization. The real question is not the description of how many levels, processes or systems exist (every categorization can be as valid as others); the question, open to determination and discussion from both scientific and philosophical perspectives, is to understand the relationship between parts or levels.

[5] https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0057:entry=su/n

[6] https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0057:entry=i(/sthmi

[7] Ludwig von Bertalanffy, General System Theory: Essays on its Foundation and Development (New York: George Braziller, 1968), 55.

[8] If reality is a place of processes, the mechanism of formation of a place, understood as a systemic/organic notion, is analogous to Whitehead’s mechanism of concrescence in the philosophy of organism, elaborated in Process and Reality. I have spoken about this important characteristic to understand the relation between parts and whole of a system in the article Place, Space, Matter, and a New Conception of Nature. On the contiguity of meanings between ‘organism’ and ‘system’ see also Place, Space, and the Philosophy of Nature.

[9] I have structured this phrase (as well as my conception of place as a processual, concrescent notion) on a Whiteheadian popular passage in Nature and Life, page 33.

[10] See note [4] above. Concerning the subdivision of social processes I also used the ‘The Social Process Triangle Model’ (created in two international conferences held in Chicago, in the ‘70s, sponsored by the American Institute of Cultural Affairs) as a reference to have an encompassing image of the infinitude of processes related to human activities that can be headed under ‘social processes’. I just selected a few representative parts of them. See The Institute of Cultural Affairs, ‘The Social Process Triangle’ in Social and Corporate Process Triangle Workshop, 1993.

[11] The ‘regenerative approach’ as an explicit design practice had its origin in the United States, in the ‘90s, with the pioneering work of landscape architect John Tillman Lyle – author of the book ‘Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development’ (1994) – whose activity is now continued by the academic centre that he contributed to create: The Center for Regenerative Studies, on the campus of the California State Polytechnic University, in Pomona. In the USA, another cultural agent working on regenerative issues and development is Regenesis Group, one of whose principals, architect Bill Reed, was a founding Board of Director of the US Green Building Council and co-founder of the LEED Green Building Rating System. Regenesis Group in the last couple of decades, promoted a systemic approach to design and a place-based framework for design practice which have a similar cultural basis and scientific background to the one that I am delineating at RSaP – e.g., Pamela Mang and Bill Reed, ‘Regenerative Development and Design’ in Sustainable Built Environments, eds V. Loftness, D. Haase (New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 2013), 478-501. In Italy, more recently, the regenerative approach to design has been sponsored by Professor Emanuele Naboni, scientific director of the architectural magazine YB-YouBuild and editor with Lisanne Havinga of the book ‘Regenerative Design in Digital Practice: A Handbook for the Built Environment’ (2019).

[12] A net-positive balance removes more greenhouse gases from the atmosphere than we emit, in order to limit global warming to 1,5°C and ensure a safe climate for future generations.

[13] The expression ‘Consorzio Agrario’ means buildings, such as granaries, used for storing products of the earth, e.g., seeds, and agricultural stocks. Those types of buildings had a great diffusion in Italy in the first part of the XX century; now, they are often abandoned or demolished, which means that we are losing their anthropological value as symbols of rural communities and ways of living which are disappearing.

Cited Works

Bohm, David. Wholeness and the Implicate Order. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Bertalanffy, Ludwig von. General System Theory: Essays on its Foundation and Development. New York: George Braziller, 1968.

du Plessis, Chrisna ‘Towards a Regenerative Paradigm for the Built Environment’. In Building Research & Information, 40(1), (2012): 7–22.

Mang, Pamela and Reed, Bill. ‘Regenerative Development and Design’. In Sustainable Built Environments, edited by V. Loftness, D. Haase (New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 2013), 478-501.

Naboni, Emanuele and Havinga, Lisanne. Regenerative Design in Digital Practice: A Handbook for the Built Environment. Bolzano: Eurac, 2019.

Norberg-Schulz, Christian. The Concept of Dwelling: On the Way to Figurative Architecture. New York: Rizzoli International Publishing, 1985.

Ruano, Javier Collado, and Pasquier, Florent. ‘Transdisciplinary’. In Handbook of the Anthropocene: Humans between Heritage and Future, edited byWallenhorst, Nathanaël, and Wulf, Christoph. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2023.

The Institute of Cultural Affairs. ‘The Social Process Triangle’. In Social and Corporate Process Triangle Workshop, 1993.

Whitehead Alfred N. Nature and Life. London: Cambridge University Press, 1934.

Image and Video Credits

Featured Image: Rehabilitation of a grain storage warehouse (ex-Consorzio Agrario), Ostiano, IT, 2024. Design Team: Calvi Rollino, Cereda, Panarese Architetti.

Renderings: Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto.

Images 01-06: Alessandro Calvi Rollino Architetto, CC BY-NC-SA.

Image 12: Chiesa di Torricella, via fondoambiente.it

Images 14-17, 23-24, 28-29: Ostiano, Regione Lombardia, Piano di Governo del Territorio – COMUNE DI OSTIANO: https://www.multiplan.servizirl.it/pgtwebn/#/public/dettaglio-piano/11371/documenti

All other images and video: Calvi Rollino, Cereda, Panarese Architetti.

CC, BY-NC-SA, RSaP-Rethinking Space and Place, 2025. All content including texts, images, documents, audio, video, and interactive media published on this website is for non-commercial, educational, and personal use only. For further information, please reach out to: info@rethinkingspaceandplace.com