By the term ‘spatiophilia’, I present the result of the photographic survey I have been conducting for a couple of years now on how people perceive and use the concepts of space and place with communicative intent in the streets of Milano, Italy.

The present epoch will perhaps be above all the epoch of space.

MICHEL FOUCAULT, Of Other Spaces

Introduction

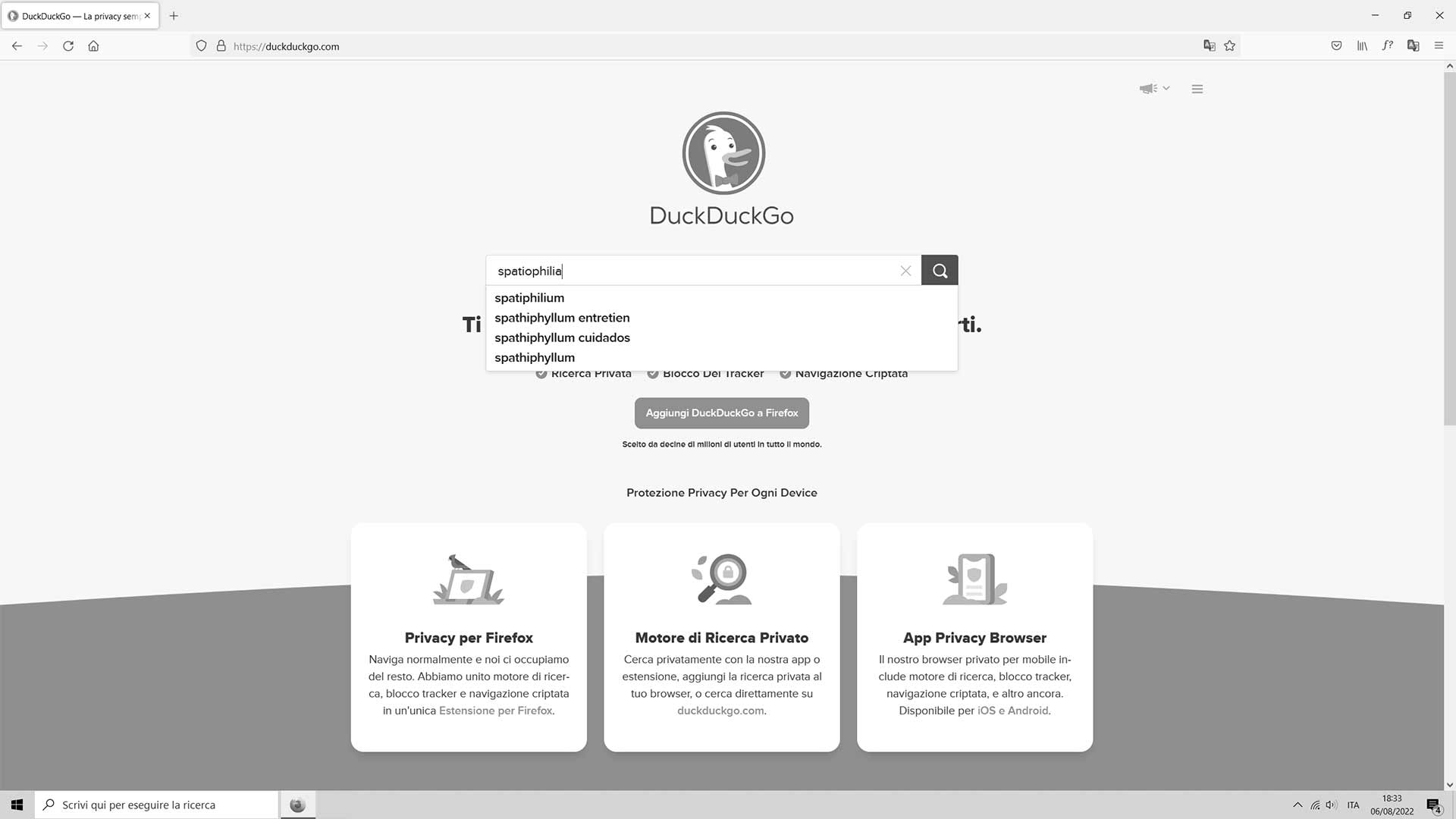

It was surprising for me when I recently typed ‘spatiophilia’ into various web search engines and got almost no results after pressing enter:[1] I was looking for a single word to concisely convey the feeling of attachment to space, or a term to express the bias people have for space and its linguistic usage in describing various environmental contexts and situations. That feeling was the outcome of the photographic report that I’m presenting here. After all, as proclaimed by Michel Foucault a few decades ago, the present epoch is ‘the epoch of space’.[2] Therefore, the existence of that phenomenon — people’s conscious or unconscious attraction to space and its widespread use to account for the description of the physical surrounding context (i.e., the circumambient world) — seemed to me a well-diffused phenomenon, even beyond the field of architecture. In the end, I was surprised that nobody used a particular term, such as spatiophilia, to describe this apparent bias for space.[3] But I think there is an explanation for that.

Scholars with an interest in the humanistic study of spatial and placial concepts likely already understand my point: here, spatiophilia is intended as the correlative expression or counterpart of ‘topophilia’, a well-known spatial term and concept since the ‘70s, when the Chinese-American geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, used it as the title of his fortunate, often-quoted book Topophilia (1974), to describe ‘the affective bond between people and place’.[4] The term topophilia was already used years before by Gaston Bachelard, in his Poetics of Space (1957, the first French edition), for which Tuan wrote a review in the Landscape Magazine (Autumn 1961, Volume 11, Issue 1); the same term was also used a few times by the British-American poet W. H. Auden, in his introduction to the book of poems by Sir John Betjeman: Slick but not Streamlined (1947). However, we can go back further to 1842 — the first published record I was able to find — to see topophilia with a slighty different, more specific, connotation as ‘habitationis amor’, the love for home or dwelling, in a Latin manual of Phrenology by the Italian physician Gaspare Moro.[5]

In both Bachelard and Foucault — see note [2] —, there was a supreme ambiguity, if not a superposition of meanings between the concepts of space and place. Philosophers Ivor Leclerc and Jeff Malpas had already observed this ambiguity or indifferentiation between the two concepts.[6] Probably, this was a good reason to include the term ‘space’ within concepts derived from the old Greek root ‘topos’ (e.g., topophilia, or even topology, which has been the name associated with the discipline that studies the properties of geometrical space since the 19th century, after Leibniz’s invention of analysis situs).[7] However, as you probably know if you have read some articles at RSaP–Rethinking Space and Place, I often reject the possibility of understanding space as a derivative notion from topos (or a synonym): this is the root cause of many confusing and ambiguous interpretations regarding the concepts of space and place in almost any domain of human knowledge. Without a specific study of the origins and histories of these two concepts, as I am trying to do at RSaP, it is almost impossible to disentangle their intricate interconnections and different gradients of meaning. By using the term spatiophilia as a counterpart of topophilia, I want to remark that spatium and topos, which are used here as representative terms for space and place, are very different concepts, not far from Heidegger’s differentiation between the two terms in the famous essay ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’.[8] Then, the two terms are deeply related, but different; a relation of continuity and opposition, I’d say. This means that topos and derivative concepts cannot indifferently play the part or resume the sense of space or place, as it seems by reading Bachelard’s and Foucault’s narratives (but they are just the tip of the iceberg). Leaving aside for the moment the ambiguities behind Bachelard’s and Foucault’s spatial terminology, and accepting Tuan’s genuine intuition, if ‘topophilia’ is ‘the affective bond between people and place’, then spatiophilia is the correlated technical term to define the bias, attachment, or preference — if not properly an affective bond or love, as the beautiful land art installation in the image below seems to suggest — that people have for space and its linguistic usage to describe different types of environmental situations (I mean ‘space’ apart from its astronomical sense: in that case we speak of spacephilia, properly — see note [3]).

Image 1: Spazio Amato (i.e., Loved Space), neon installation by the italian artist Massimo Uberti, Capalbio (GR), Italy, 2020 (Info: Hypermaremma.com).

Spatiophilia: a photographic report on how the concepts of space (spazio) and place (luogo) are perceived and used with communicative intent in Milano’s streets

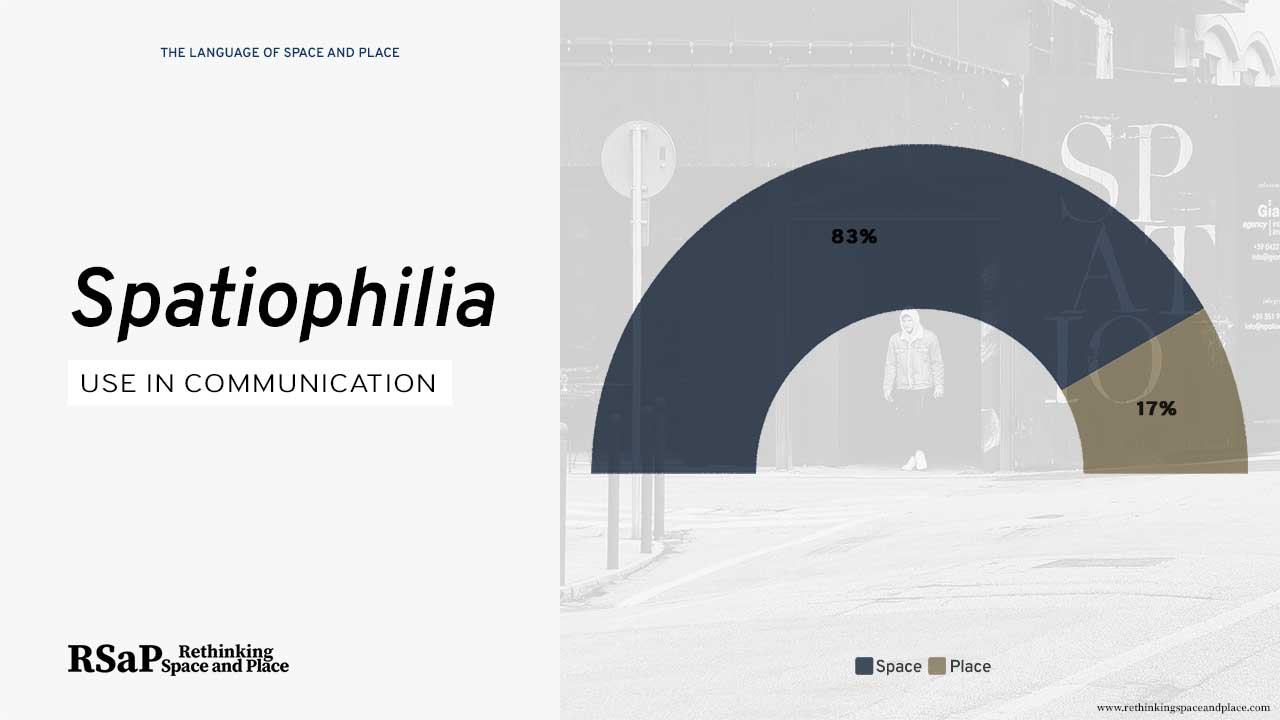

I couldn’t find a better way to synthesize in other terms than spatiophilia the findings of the report that I’m presenting in the photographic galleries below, after conducting surveys for over two years: I wanted to explore how the concepts of space and place were perceived and used with communicative intent in the streets of Milano, my city of birth. Sometimes used interchangeably, in the same context and with the same intent, sometimes not, there is a noticeable imbalance in how frequently ‘space’ is used compared to ‘place’. There is a clear bias towards using the word ‘space’ instead of ‘place’ to describe specific or generic environmental situations, such as apartment rooms, shops, offices, showrooms, classrooms, buildings, parks, flowerbeds, streets, squares, and so on, as evident from the 50 galleries of 300 images below, which show a 5-to-1 ratio of ‘space’ to ‘place’ usage. That is: the word ‘space’ (in Italian, spazio) appears five times more frequently than the word ‘place’ (luogo) in signs, billboards, shop windows, public warnings, street banners, activity descriptions, handwritten notes, tags, stickers, and so on. This suggests that modern humans have a space-biased mindset rather than a place-biased one, meaning that one tendency is more abstract than the other: we tend to think we inhabit a domain of space, overlooking the fact that our reality is fundamentally a concrete realm composed of specific situations, places, or locales. This (natural? induced?) tendency or bias that people have for space is what I mean here by spatiophilia. After all, in recent decades, the tendency to abstractly understand and describe our environments has been indirectly proven by the success of concepts like ‘non-places’ (Marc Augé) and ‘placelessness’ (Edward Relph) in social and political contexts. At RSaP, I argue that this spatially-biased, metaphorical, and abstract vision of reality, if not balanced by more concrete attitudes, is the root of dangerous distortions that affect crucial contemporary issues, including biological, environmental, social, political, economic, architectural, and urban questions. These questions are inextricably linked to how we perceive reality — i.e., the surrounding environment — in terms of space and/or place, that is in terms of permeability/impermeability, presence/absence of limits, borders, boundaries, thresholds, and other liminal notions that shape our understanding of place and space. To address these crucial contemporary issues with the most appropriate theoretical tools, we must rethink space and place as complementary concepts, covering the entire spectrum of reality, from concrete, material, and qualitative aspects (place) to abstract, ideal, and quantitative aspects (space). In this way, we should prevent one aspect of reality from cannibalizing the other, as is particularly evident in our current epoch – ‘the epoch of space’ – where our sense of place has been buried in space and other recently discovered symbolic realms, such as artificial, digital, hybrid, and virtual worlds.

In the past decades, architectural historians and critics Kenneth Frampton and Christian Norberg-Schulz have associated the excessive emphasis on environments understood as space with some of the distortions in our universal civilization, among them the loss of place.[9] To borrow a concept from Norberg-Schulz, which perfectly adapts to the phenomenon we are describing, ‘spatiophilia’ could be seen as a sign of ‘a growing trend in this direction: the qualitative world with all its immediacy has fallen victim to quantification, which estranges us from the deeper meanings of our everyday experiences’.[10] Here, ‘the qualitative world with all its immediacy’ refers to the world immediately accessible to us, expressed by concrete names such as shop, school, park, square, office, beauty salon, etc., which are all names for specific places that evoke certain activities and experiences. Conversely, the ‘quantification, which estranges us from the deeper meanings of our everyday experiences’, refers to the inalienable, abstract, quantitative connotation of space, originally meaning a distance, measure, or extension, which are all abstract and neutral determinations. In other words, place has been overshadowed by space, as the photographic report also implies, because we often substitute the names of specific, meaningful things or places, which hold qualitative and experiential values and memories, with the more abstract and neutral term space, which lacks these values. A loss of descriptive quality, a linguistic loss, which reflects the loss of place ‘that has its origins in an inadequate understanding of the environment’ and is a cause of human alienation, according to Norberg-Schulz.[11] With different words but similar intent, this inadequate understanding of the environment due to the power of abstraction (i.e., the power of space–we are suggesting), which is one important factor of human alienation, has also been described by the physicist and system thinker Fritjof Capra in the following terms: ‘The power of abstract thinking has led us to treat the natural environment – the web of life – as if it consisted of separate parts, to be exploited by different interest groups. […] The belief that all these fragments […] are really separate has alienated us from nature and from our fellow human beings and thus has diminished us.’[12] Behind the power of abstract thinking lies space, which serves as a divisive factor, both etimologically, metaphorically, and ‘physically’. Even according to the American novelist and poet Wendell Berry, this psychological distance from the places we are part of – a distance that removes our intimacy with the flesh of reality – is reflected in the abstract vocabulary we use in our descriptions. With the same fundamental principle, but more radically than I am doing here addressing this alienating sentiment to space, Berry challenges the abstracting function of language (he even considers the term ‘environment’ too abstract), which is ‘incapable of giving a true description of our relation to the world’, and, therefore, he describes it as ‘academic, artificial and pretentious’,[13] concluding his attack to the bifurcating power of abstract language with exactly the same message that ‘spatiophilia’ wants to convey: ‘The real names of the environment are the names of rivers and river valleys; creeks, ridges, and mountains; towns and cities; lakes, woodlands, lanes, roads, creatures, and people.’[14] Only concrete names of things can convey our intimacy with the world’s physicality, unlike the neutral term ‘space’, which inherently implies distance between things. How can we reconnect with the world and its components on a psychological and spiritual level if our language perpetuates bifurcation, separation and division?

Space, as a widespread mode to describe the environment, has contributed to reducing people’s original understanding of their surroundings, or place, to a neutral realm without any distinct characteristics, much like a system of geometric coordinates or modern GPS coordinates. This is an abstract conception of the environment, where space has taken the role that, in antiquity, the ancient atomists assigned to the void. And no matter how hard physicists and phenomenologists, especially, have tried to convince us that space is not void and can be the conveyor of temporal and material, or even qualitative and existential characters: common people, including practitioners, entrepreneurs, stakeholders, and politicians, remain unfamiliar with relativity, quantum mechanics, and phenomenology. If, as Confucius affirms in The Analects, ‘the beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name’, let’s start calling a spade a spade again.[15] An office, office–plain and simple. A flowerbed, flowerbed. A place, place. I believe physicists, philosophers, social scientists, architects, artists and laymen could all benefit from that.

space… the most obsessing of metaphors in today’s languages

MICHEL FOUCAULT, The Language of Space

Video 1: SPAZIO PREMUDA. ‘Space’ carved into the asphalt, Milano, Italy.

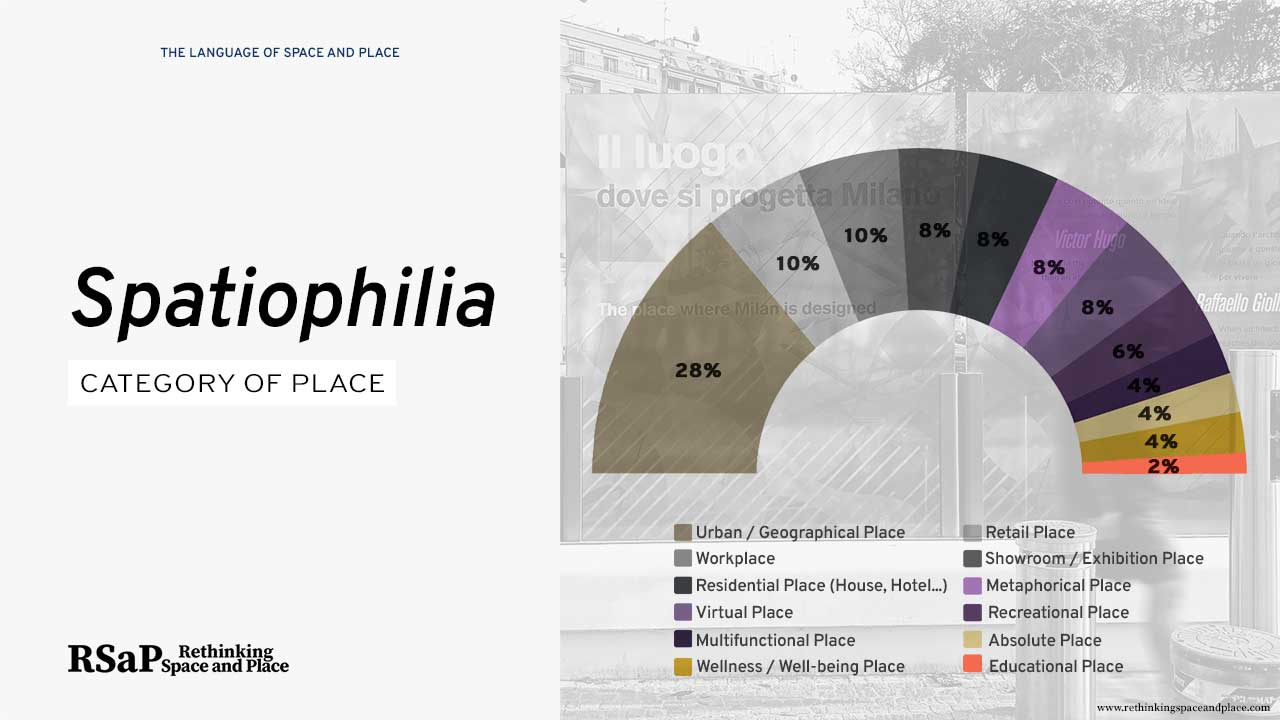

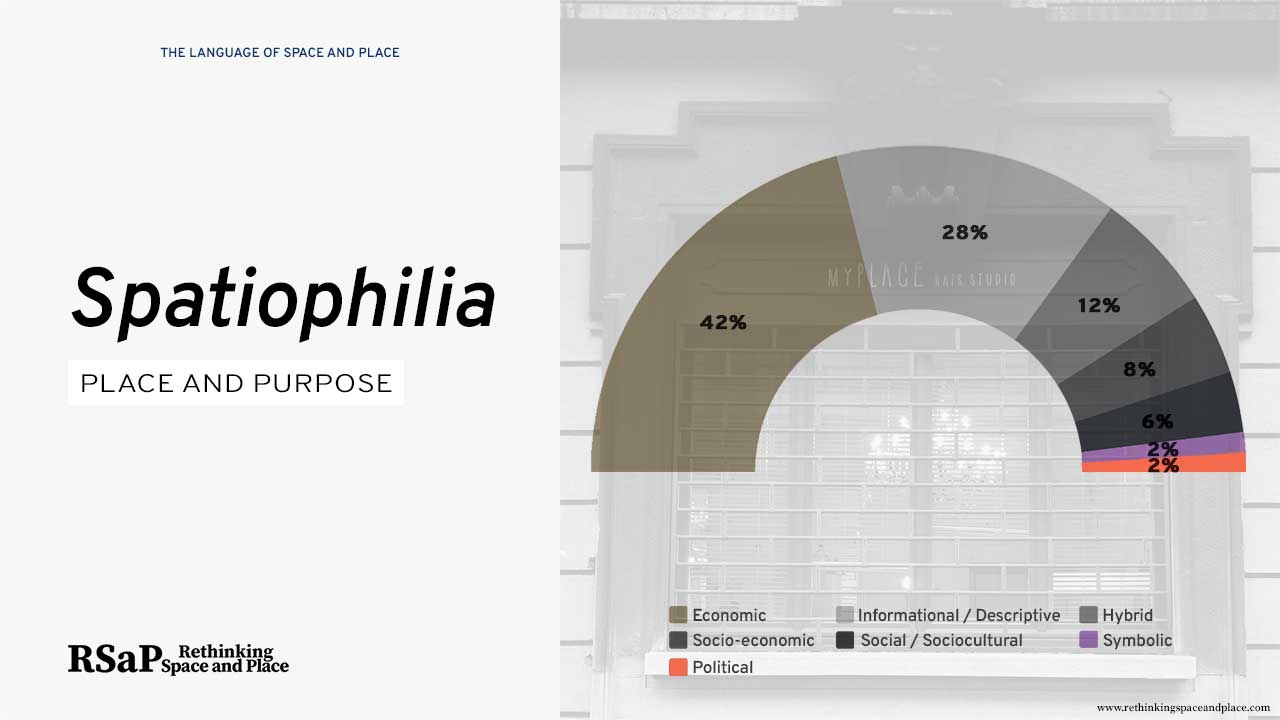

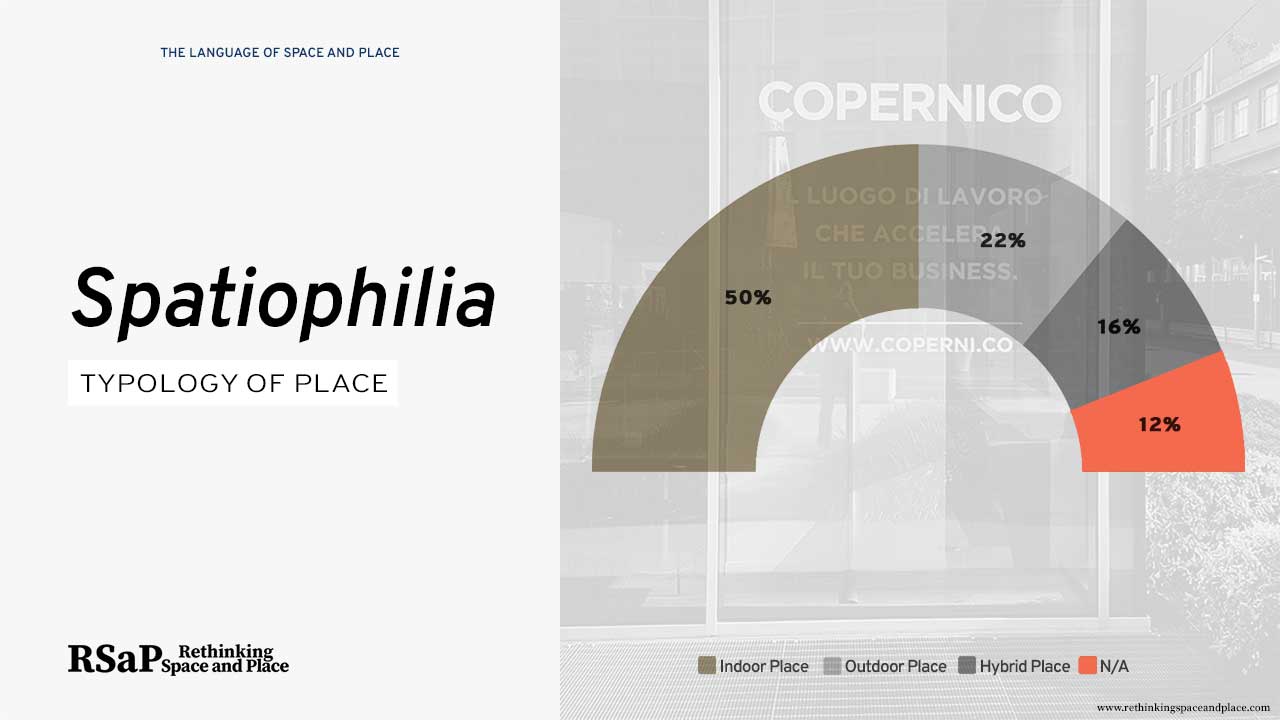

Spatiophilia in charts and numbers

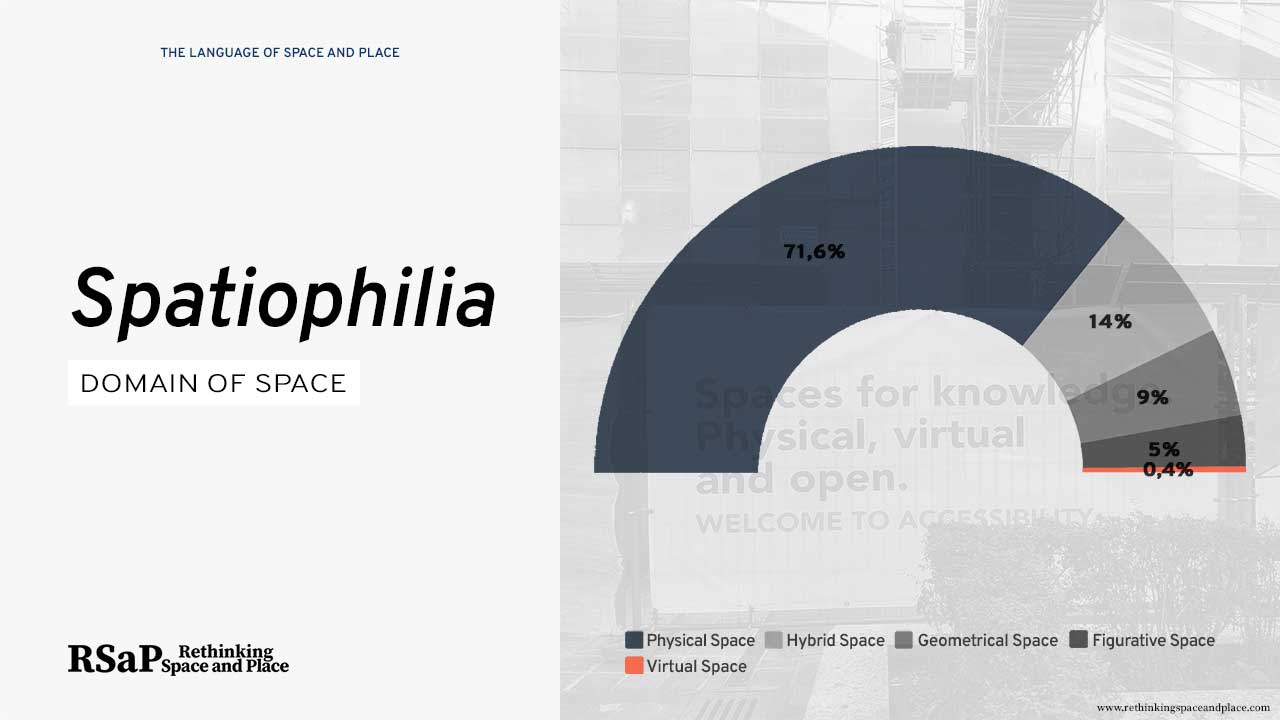

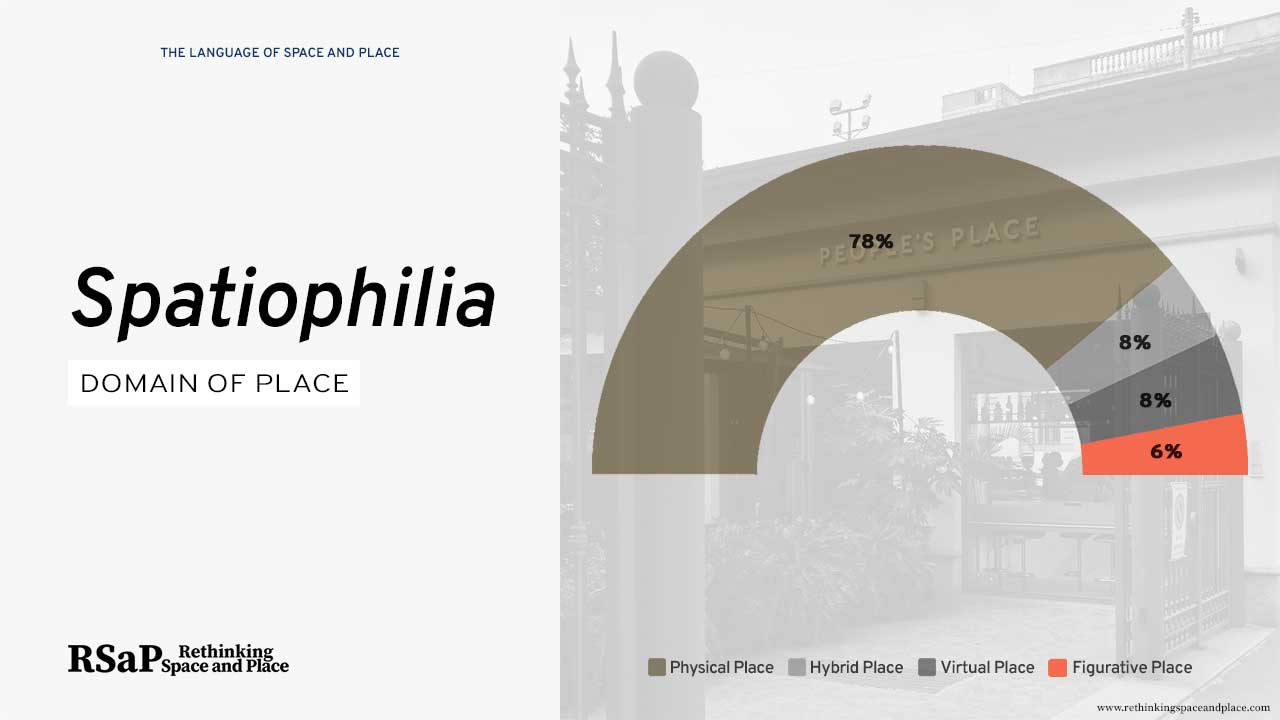

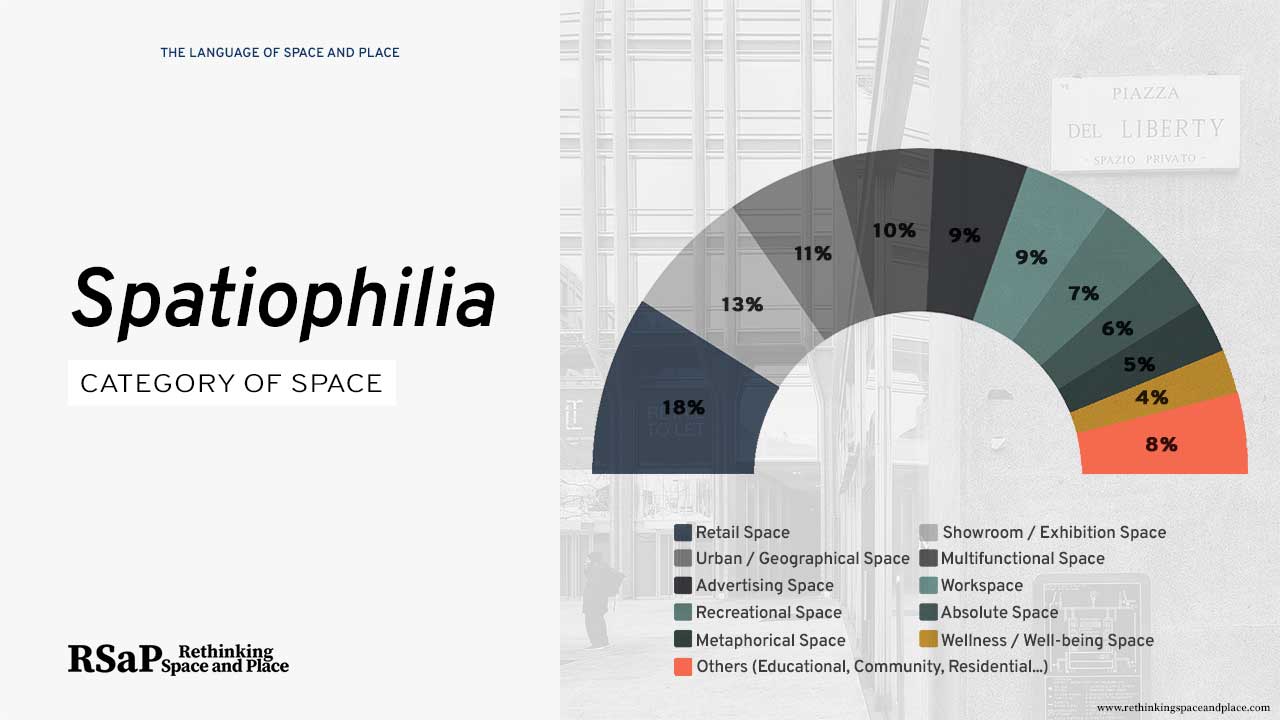

In the slideshow above, I have included some charts that I derived from the analysis of the 300 hundred photographic shots you find in the galleries below. With those charts and numbers, I wanted to offer further material to ponder spatial questions. These charts propose a tentative hypothesis to explore the connections between spatial language and the society that created and developed it – namely, our modern ‘universal civilization’ in ‘the epoch of space’. If I had to choose one reasonable argument for discussion among others, I would select the reciprocal influence between the development and diffusion of the common concept of space, on one hand (our traditional idea of space is the translation into ordinary language of the XVII-century conception of absolute space from physics – space as the neutral stage for processes), and the development and diffusion of modern capitalistic economy and finance, on the other. Why such a suggestion? It seems to me, as the images also suggest, that the term ‘space’ is frequently associated with activities or situations that ultimately serve economic purposes. Economic processes are becoming increasingly abstract, often disregarding local ecological and sociocultural processes, and are frequently based on the provision of services or the even more abstract productive aspects of information technology. This raises the question: How functional were the conceptual ‘triumph of space’ (space, the neutral, abstract container which is not rooted in any specific territorial reality or activity) and the correspondent ‘demise of place’ or ‘loss of place’ (place, the responsive container which is rooted in actual territorial realities and activities) to economic plans and processes, since the first Industrial Revolution? Conversely: To what extent did human plans and processes focused on economic strategies and business forms always growing in abstraction (from the production of physical goods to the provision of services, knowledge, and information) contribute to the ‘triumph of space’ and the ‘demise’ or ‘the loss of place’? [16]

Foucault expressed his understanding of modern society in terms of space in the 1960s, parallel to the sentiment expressed by Paul Ricoeur in ‘History and Truth’, 1965, where, regarding the emergence of a flattening, universal civilization, he talked about ‘a sort of subtle destruction, not only of traditional cultures […] but also of […] the ethical and mythical nucleus of mankind.’[17] As previously mentioned, architects, historians, and critics Kenneth Frampton and Christian Norberg Schulz intercepted this sentiment, proposing a shift towards place in the 1970s and 1980s to rescue architecture and cities from the monotony and standardization associated with space (the key-concept of modern architecture), which was seen as a vehicle for universal, abstract, and alienating aspects. However, this request for a turn towards place-based development was contrasted by real events that went in the opposite direction–the direction of ‘spatiophilia’: in fact, during the 1980s and 1990s, the adoption of neo-liberal, free-market economic policies emphasizing privatization of enterprises and services to combat global recession led to the proliferation of multinational corporations and their business plans, which transcended national governments and borders, promoting the diffusion of a universal civilization (i.e., globalization) even more than in the past.[18] Space, an un-limited domain, is what these multinational corporations required for their plans, for the open and uninterrupted (i.e., unbounded) flow of goods and capital, and space, open and unbounded, is what they got–what we got. Even language has been increasingly influenced by space, especially in recent decades: this abstracting trend is leading to the replacement of traditionally concrete, place-based terminology, as the photographic report suggests. For example, old ‘cultural centers’ (‘center’, a term with specific place-based connotations) are now often referred to as ‘cultural spaces’. Similarly, ‘kindergartens’ are being replaced by ‘spaces for kids’, ‘flowerbeds’ by ‘green spaces’, and students or activists are reclaiming spaces instead of places for studying, socializing, dwelling, etc. This shift illustrates a broader movement toward a more abstract (detached…) sense of community and its immediate environment. This is the historical phenomenon that ‘spatiophilia’ illustrates.

To conclude this presentation on the spatiophilia phenomenon, I’d like to consider the future development of spatial language and concepts. As I said in the Preliminary Notes to this website, over the past century, a new understanding of nature has been emerging, and a reformulation of spatial concepts is underway; this fact of incomparable scientific, sociocultural, and intellectual relevance, coupled with another relevant fact of our contemporary epoch – the environmental question and the discovery of climate change exacerbated by anthropic factors – is inverting the trend of interest between abstraction and concreteness, between ‘space’ and ‘place’ ultimately. A new necessity from different social, economic, and cultural actors is felt to link processes and events to the actual reality where processes are located – this meaning a return to ‘place’, independently of the fact that ‘place’ is the term we use for a building, a urban district, a territorial region, planet Earth, or the Universe at large. If this trend continues over the coming decades and centuries, a more balanced spatial vocabulary can be expected to develop in order to describe phenomena and events between physical, abstract (or metaphorical), and new virtual worlds. However, there is no absolute certainty about this expectation, as the recent emergence of artificial, virtual, hybrid, and digital worlds, along with information technologies, presents a new counterforce if a return to place and concreteness is still and will remain an actual concern, as observed by Frampton, Norberg-Schulz or Casey (see note 15, below). The global spread of service economies, financial capitalism, and information technologies reinforces our natural inclination towards abstraction and our affinity for spatial domains – our spatiophilia.

Conclusive remarks

‘To rethink space as place – and not the reverse, as in the early Modern Era…’ is the urgent task of many contemporary thinkers, the American philosopher Edward S. Casey concluded in the book The Fate of Place,[19] indirectly pointing out the dangers inherent in traditional forms of spatial understanding and descriptions. The photographic report reveals that the term ‘space’ is often misused in various contexts, where more specific terms like, for instance, ‘place’, ‘locale’, ‘location’, ‘room’, ‘classroom’, ‘park’, ‘shop’, ‘office’, ‘street’, or ‘square’ could provide a more accurate and nuanced understanding of an immediate situation or its qualitative and experiential character. The critical attention that contemporary scholars and practitioners are directing towards traditional and more recent spatial or placial terminology, using terms like ‘place’, ‘atmosphere’, ‘ambience’, ‘environment’, ‘region’, ‘bioregion’, etc., to describe concretely experienced contexts, situations, and backgrounds can be seen as an indication of the ongoing shift of interest from the inherently abstract and neutral character of space to the more concrete qualities of places (see also From Space to Place: A Necessary Paradigm Shift…). However, abstracting forces, such as the spread of free-market economic policies, information technologies, and artificial or virtual worlds, must be counteracted before we can adopt a more balanced attitude towards the environments we belong to, in between space-based and place-based understanding and descriptions.

Spatiophilia: Image Galleries

Gallery 01 (Images 01-06)

Gallery 02 (Images 07-12)

Gallery 03 (Images 13-18)

Gallery 04 (Images 19-24)

Gallery 05 (Images 25-30)

Gallery 06 (Images 31-36)

Gallery 07 (Images 37-42)

Gallery 08 (Images 43-48)

Gallery 09 (Images 49-54)

Gallery 10 (Images 55-60)

Gallery 11 (Images 61-66)

Gallery 12 (Images 67-72)

Gallery 13 (Images 73-78)

Gallery 14 (Images 79-84)

Gallery 15 (Images 85-90)

Gallery 16 (Images 91-96)

Gallery 17 (Images 97-102)

Gallery 18 (Images 103-108)

Gallery 19 (Images 109-114)

Gallery 20 (Images 115-120)

Gallery 21 (Images 121-126)

Gallery 22 (Images 127-132)

Gallery 23 (Images 133-138)

Gallery 24 (Images 139-144)

Gallery 25 (Images 145-150)

Gallery 26 (Images 151-156)

Gallery 27 (Images 157-162)

Gallery 28 (Images 163-168)

Gallery 29 (Images 169-174)

Gallery 30 (Images 175-180)

Gallery 31 (Images 181-186)

Gallery 32 (Images 187-192)

Gallery 33 (Images 193-198)

Gallery 34 (Images 199-204)

Gallery 35 (Images 205-210)

Gallery 36 (Images 211-216)

Gallery 37 (Images 217-222)

Gallery 38 (Images 223-228)

Gallery 39 (Images 229-234)

Gallery 40 (Images 235-240)

Gallery 41 (Images 241-246)

Gallery 42 (Images 247-252)

Gallery 43 (Images 253-258)

Gallery 44 (Images 259-264)

Gallery 45 (Images 265-270)

Gallery 46 (Images 271-276)

Gallery 47 (Images 277-282)

Gallery 48 (Images 283-288)

Gallery 49 (Images 289-294)

Gallery 50 (Images 295-300)

Notes

[1] Actually, I got two false positives from a book written in 1538 by Pietro Bembo, an Italian scholar and Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church: here, the algorithm of the search engine misplaced ‘spatiophilia’ for the bastard Latin-Italian expression ‘spatiosa sia’, which, in the original treatise, was written with a baroque style which could have deceived the algorithm.

Slideshow (below): The unsuccessful query for the term spatiophilia on different web search engines.

Post Scriptum (Dec 2024): Meanwhile, information technology has blessed us with the help of Artificial Intelligence making our way to knowledge ‘easier’. So, I prompted ChatGPT with the question: ‘What is spatiophilia?’ In the image below you will find the answer, but do not expect too much, apart from the obvious juxtaposition of the meaning of the two words ‘spatio’ + ‘-philia’, where ‘spatio’ indifferently plays the part of ‘space, places, or environments’, which means that, for the AI, there is no real distinction between ‘topophilia’ and ‘spatiophilia’. After all, that makes sense given that the photographic report points out a phenomenon that often goes unnoticed: the common habit of skipping distinctions between space and place, given that parks, flowerbeds, streets, plazas, shops, schools, etc., which are all places, are named ‘space’. But, as I have said in the text, I reject that common habit: there are linguistic, historical, physical, philosophical, and psychological divides between space and place and, therefore, between ‘topophilia’ and ‘spatiophilia’.

Unsatisfied with the answer given by AI, yet, curious about its staggering, mechanical ‘intellectual’ ability, I asked for the meaning of ‘nothingfilia’ and its opposite, ‘whateverphilia’—the first absurd ‘philias’ that came to my mind. Almost instantly, I realized that Artificial Intelligence was far ahead of me, responding in the blink of an eye with serious answers suggesting me that, one day, I could meet a nothingfiliac or a whateverphiliac along my way.

[2] In a manuscript prepared for a conference held in Tunis, in 1967, at the Cercle d’études architecturales, and later published and translated into English with the title ‘Of Other Spaces’, Michel Foucault wrote: ‘The present epoch will perhaps be above all the epoch of space.’ In Michel Foucault, ‘Of Other Spaces’, Diacritics, Spring 1986, 22. I must point out that in that brief essay, it is difficult to disentangle concepts of space and place, which are indiscriminately included within the term topos and derived terminology (e.g., utopias, heterotopias). It seems topos takes it all. For me, that is a limit in Foucault’s otherwise-interesting analysis of space and place (heterotopology or heterotopoanalysis), as also Edward Casey observed in The Fate of Place: ‘heterotopology… harbours three problems. First, Foucault nowhere makes a clear, much less a rigorous distinction between such basic terms as “place”, “space”, “location” and “site”. As a consequence, these terms are often run together or interchanged indifferently…’ In Edward Casey, The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997),300.

[3] Of course, immediately after the search for spatiophilia, I wanted to see if there could be some ‘more popular’ variations of the same concept: so, I typed the less-fascinating, but certainly more popular word spacephilia, and, as I expected, I found a lot of results concerning different Institutions and individuals who have an attraction or attachment for astronomical space. In addition to the attraction for space in the astronomical sense, I found one Instagram account of an Interior Design Company presenting some zenithal images of tables and chairs with their respective measures to see the extent that people need to move around tables and chairs (the floor-space or area taken up by furniture is the ‘ABC’ of architects and house-planners). So, in the end, even the more popular term ‘spacephilia’ did not give me the indications I was looking for.

[4] Yi-Fu Tuan, Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values (New York: Columbia University Press, 1974), 4.

[5] Casparis Moro, Brevis Phrenologiae Expositio (Patavii: Typis Penada, MDCCCXLII), 15.

[6] Leclerc said: ‘Today the prevailing presupposition is that the term [space] has one fundamental basic meaning which is constant […]; there is extraordinarily little appreciation of the shifts in sense of the various occurrences of its usage, even in the same writer, and often in the same sentence or paragraph. This variation in sense is further confounded by the use of space […] as synonymous with place’, in Ivor Leclerc, The Philosophy of Nature (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1986), 97. Even more specific regarding Bachelard’s use of spatial terminology, Malpas noted: ‘… many of the discussions of place in the existing literature suggest that the notion is not at all clearly defined. Concepts of place are often not distinguished at all from notions of simple physical location, while sometimes discussions that seem implicitly to call upon notions of place refer explicitly only to a narrower concept of space. Is Bachelard’s Poetics of Space, for example, really about place or space?’, in Jeff Malpas, Place and Experience: A philosophical Topography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 19.

[7] We read from the historian of philosophy and science Vincenzo De Risi: ‘…topology… was usually called “analysis situs” in the 19th century‘. In Vincenzo De Risi, ‘Analysis Situs, the Foundations of Mathematics and a Geometry of Space’ in The Oxford Handbook of Leibniz, ed. M.R. Antognazza (Oxford: Oxford univeristy Press, 2019), 250.

[8] Heidegger, in ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’, attributed space and place different meanings and values: qualitative and primary, or existential, is the nature of place, which allows the existence and presence of things (place offers room to things) as concrete, qualitative facts, according to original Greek meaning topos; quantitative and subordinate, or dimensional is the nature of space — which is the modern, traditional way of understanding of space (where trigonometry applied to astronomy and geometry applied to physics are highly relevant historical moments for such understanding) — originally, from the Latin ‘spatium’ as distance, measure, or interval (analogously to the Greek ‘spadion/stadion’ — I’ve talked about that in the article Back to the Origins of Space and Place), and ‘extensio’. In Martin Heidegger, ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’. In Basic Writings, ed. by David Farrel Krell (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993), 357. The subordinate nature of space is reinforced by Heidegger’s often-quoted remark that ‘spaces receive their essential being from locales [i.e. places] and not from space’, which is present in the same text.

[9] Concerning Frampton’s position on the dichotomy between place and space and the necessity to refer to place rather than space to face some of the problems of our ‘universal civilization’, see paragraph ‘2.1 Architecture, Place and the Spirit of Time: Different Forms of Regionalism’ in the article The Place of Architecture The Architecture of Place – Part II: A Historical Survey. Concerning Norberg-Schulz’s reference to ‘the loss of place’ – exposed in the book Genius Loci – due to the transposition of space-based techniques from architecture to urban planning see paragraph ‘2.3 Presence and the Human Body: Existential and Phenomenological Approaches to the Architecture of Place’ in the same article.

[10] Christian Norberg-Schulz, Architecture: Presence, Language and Place (Milano: Skira Editore, 2000), 20.

[11] Ibid., 59, 74. See also: Christian Norberg-Schulz.Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1980), 189.

[12] Fritjof Capra, The Web of Life (New York: Anchor Books, 1996), 296.

[13] Wendell Berry, Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community: Eight Essays (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993), 34-35.

[14] Ibid., 35.

[15] See Confucius on Names and Things.

[16] The terminology ‘triumph of space’ and ‘demise of place’ follows the interesting narrative on the history of the concepts of space and place explained by Edward Casey in ‘The Fate of Place’ (see the article Place and Space: A Philosophical History). The terminology ‘the loss of place’ is taken from Norberg-Schulz, see notes [8] and [10] above.

[17] Kenneth Frampton, ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism. Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance’, in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern, ed. Hal Foster, 2019, 16.

[18] cited in Chrisna du Plessis, ‘Towards a Regenerative Paradigm for the Built Environment’, in Building Research & Information, 40:1 (2012): 11. For an overview of the phenomenon of globalization and its implication on spatial/placial boundaries see Jessica T. Mathews, ‘Power Shift’ in Foreign Affairs, 76, 1 (1997): 50-66.

[19] Edward Casey, The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 309.

Works Cited

Augè, Marc. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, translated by John Howe. London: Verso, 1995.

Berry, Wendell. Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community: Eight Essays. New York: Pantheon Books, 1993.

Capra, Fritjof. The Web of Life. New York: Anchor Books, 1996.

Casey, Edward. The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

du Plessis, Chrisna. ‘Towards a Regenerative paradigm for the Built Environment’. In Building Research & Information, 40:1 (2012): 7-22.

Foucault, Michel. ‘Of Other Spaces’, in Diacritics, Spring 1986.

–. ‘The Language of Space’, in Geography, History and Social Sciences edited by Georges Benko and Ulf Strohmayer, The GeoJournal Library, vol 27. Dordrecht: Springer, 1995.

Frampton, Kenneth. ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance’. In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern, edited by Hal Foster, 2019.

Heidegger, Martin. ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’. In Basic Writings, edited by David Farrel Krell, 347-363. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993.

Leclerc, Ivor. The Philosophy of Nature. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1986.

Malpas, Jeff. Place and Experience: A philosophical Topography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Mathews, Jessica T. ‘Power Shift’. In Foreign Affairs, 76, 1 (1997): 50-66.

Norberg-Schulz, Christian. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1980.

–. Architecture: Presence, Language and Place. Milano: Skira Editore, 2000.

Relph, Edward. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion Limited, 1976.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974.

Image Credits

Featured Image, Video, and all other images in the Slideshows and the Galleries above by Alessandro Calvi Rollino, CC BY-NC-SA.

Image 1 (source) Spazio Amato, installation, on insideart.eu